Abstract

Background. “Smart’” polymers with reversible responsiveness to temperature stimuli are among the most promising carriers for controlled drug delivery, as temperature is a critical physiological factor within the human body. The majority of studies on the coupling of polymers with active substances have employed the method of attaching the drug to the polymer after its synthesis. The direct addition of the drug during the polymerization process has not been attempted, primarily due to concerns about the potential degradation of the active substance under harsh reaction conditions, such as elevated temperature and the presence of free radicals.

Objectives. This study aimed to evaluate the stability of a selected model drug – naproxen sodium (NAP), under extreme synthesis conditions, thereby providing insights into its resilience in such an environment.

Materials and methods. The Thermo Scientific Dionex UltiMate 3000 system was utilized for the chromatographic analyses. The separations were carried out on a Phenomenex Kinetex 2.6 µm, C18 100A, 150 × 2.1 mm column at 30°C. A high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay was carried out using gradient elution with a flow rate 0.4 mL/min and mobile phase of water 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile 0.1% formic acid (B) with the detector set at the wavelength of 254 nm.

Results. Chromatographic analysis showed new peaks indicating decomposition on NAP in ambient temperature in the presence of 2.2’-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AIBA).

Conclusions. Our findings indicate that NAP cannot be combined with the polymer during the polymerization process in extreme conditions of synthesis, specifically at temperatures of 70°C and in the presence of radicals, without undergoing decomposition. Nevertheless, further trials and tests are necessary to substantiate this hypothesis. One potential avenue for further investigation would be trials with alternative radical initiators, such as potassium persulfate (KPS).

Key words: naproxen sodium, 2.2’-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Abstract (in Polish)

Wprowadzenie. „Inteligentne” polimery wykazujące odwracalną reaktywność na bodźce temperaturowe są uważane za jedne z najbardziej obiecujących nośników do kontrolowanego dostarczania leków, ponieważ temperatura jest krytycznym czynnikiem fizjologicznym w organizmie człowieka. W większości badań dotyczących łączenia polimerów z substancjami aktywnymi stosowano metodę przyłączania leku do polimeru po jego syntezie. Nie podejmowano prób bezpośredniego dodawania leku podczas procesu polimeryzacji, głównie ze względu na obawy o potencjalną degradację substancji czynnej w ostrych warunkach reakcji, takich jak podwyższona temperatura i obecność wolnych rodników.

Cel pracy. Celem badania była ocena stabilności wybranego leku modelowego – naproksenu sodowego (NAP) – w ekstremalnych warunkach syntezy.

Materiał i metody. Do analiz chromatograficznych wykorzystano system Thermo Scientific Dionex UltiMate 3000. Separacje przeprowadzono na kolumnie Phenomenex Kinetex 2,6 µm, C18 100A, 150 × 2,1 mm w temperaturze 30°C. Badanie HPLC przeprowadzono przy użyciu elucji gradientowej z szybkością przepływu 0,4 ml/min i fazy ruchomej składającej się z kwasu mrówkowego 0,1% w wodzie (faza A) oraz kwasu mrówkowego 0,1% w acetonitrylu (faza B) z detekcją przy długość

fali 254 nm.

Wyniki. Analiza chromatograficzna wykazała obecność nowych pików wskazujących na rozkład NAP w temperaturze otoczenia w obecności dichlorowodorku 2.2’-azobis(2-metylopropionamidyny) (AIBA).

Wnioski. Wyniki badań wskazują, że NAP nie może być łączony z polimerem podczas procesu polimeryzacji prowadzonego w ekstremalnych warunkach syntezy, w szczególności w temperaturze 70°C i w obecności rodników, ponieważ ulega degradacji. Niemniej jednak konieczne są dalsze próby i testy w celu potwierdzenia tej hipotezy. Jednym z potencjalnych kierunków dalszych badań byłyby próby z alternatywnymi inicjatorami rodnikowymi, takimi jak nadsiarczan potasu (KPS).

Key words (in Polish): naproksen sodowy, dichlorowodorek 2.2’-azobis(2-metylopropionamidyny), wysokosprawna chromatografia cieczowa (HPLC)

Background

Polymers, particularly thermosensitive polymers, serve as a crucial class of drug carriers, enabling both the transportation of active ingredients and their controlled release. This capability significantly enhances the therapeutic efficacy and bioavailability of drugs. Polymers in drug delivery systems enable the modification of release profiles to meet specific therapeutic requirements.1 The growing use of thermosensitive polymers in advanced drug delivery systems is driven by their biocompatibility, biodegradability and ability to undergo structural or property changes in response to temperature fluctuations.2, 3, 4 These polymers can remain insoluble at body temperature but undergo structural transitions upon heating, leading to controlled drug release.5 In most cases, drugs are incorporated into thermosensitive polymers after polymerization. This method stabilizes both the carrier and the active ingredient, minimizing the risk of chemical reactions that could compromise drug efficacy and polymer integrity.6, 7 Additionally, this approach allows for precise control over the structure and properties of both the carrier and the drug substance, which is essential for ensuring safety and therapeutic efficacy.

An alternative approach, which is less common, involves incorporating the active ingredient during the polymerization process. This approach is less frequently employed due to the inherent risks associated with uncontrolled reactions that may result in drug or polymer degradation.8, 9 Nevertheless, this method may confer advantages in the creation of more integrated systems that facilitate enhanced stability and control of drug release.10, 11 However, it is imperative to exercise caution when selecting monomers and polymerization techniques in order conditions to minimize the risk of drug degradation.12

The advent of modern polymerization techniques allow for more precise adjustments, promoting safer and more efficient drug–polymer binding at the polymerization stage under controlled conditions.13, 14, 15, 16 Nevertheless, in order to develop stable and safe thermosensitive polymeric systems with enhanced stability and safety, it is essential to gain insight into the nature of drug–polymer interactions and their behavior in complex biological environments. This would facilitate the full realization of the polymer potential of these systems in the context of medicine.17, 18

Objectives

The objective of this study was to evaluate the chemical stability of naproxen sodium (NAP) under extreme conditions commonly encountered during synthesis processes. Specifically, the study aimed to investigate the compound’s behavior at an elevated temperature of 70°C and in the presence of radicals generated by 2.2’-azobis(2-

-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AIBA), a thermal radical initiator. These conditions simulate a high-stress environment that could potentially lead to the degradation of NAP. The study seeks to provide insights into the resistance of NAP to thermal and radical-induced degradation, facilitating the optimization of synthesis protocols and ensuring product quality. Retention times will serve as the basis for qualitative analysis.

Materials and methods

Reagents: NAP was a free sample from Hasco-Lek S.A. (Wrocław, Poland), while 97% AIBA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sternheim, Germany). The deionized water (<0.06 μS cm−1) was filtered using an HLP 20 system with a 0.22 μm microfiltration capsule (Hydrolab, Straszyn, Poland). It met the requirements of the PN-EN ISO 3696:1999 standards for analytical laboratories. All chemicals and solvents were used as received without further purification or modification. Chromatographic solvents used were formic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich) and demineralized, bi-distilled water. The Thermo Scientific Dionex UltiMate 3000 system (Thermo Scientific Dionex, Sunnyvale, USA), equipped with an LPG-3400SD pump module, WPS-3000TSL autosampler, and TCC-3000SD column oven, a UV DAD-3000 detector, RI RefractoMax 521 refractometric detector, and FLD-3400RS fluorescence detector were utilized for the chromatographic analyses. The separations were performed on an Phenomenex Kinetex 2.6 μm, C18 100 Å, 150 × 2.1 mm column at a temperature of 30°C. A high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay was carried out using gradient elution with a flow rate 0.4 mL/min and mobile phase of water 0.1% formic acid (phase A) and acetonitrile 0.1% formic acid (phase B) with the detector set at the wavelength of 254 nm. A 5-μL sample was injected into the column, with a total run time of 13 min. The subsequent gradient elution began with 35% mobile phase B, maintained for 2 min. Then, mobile phase B was increased to 95% over 5 min and held at this level for an additional 2 min. From the 9th to the 10th min, the gradient returned to 35% mobile phase B, where it remained stable until the 13th min.

Results and Discussion

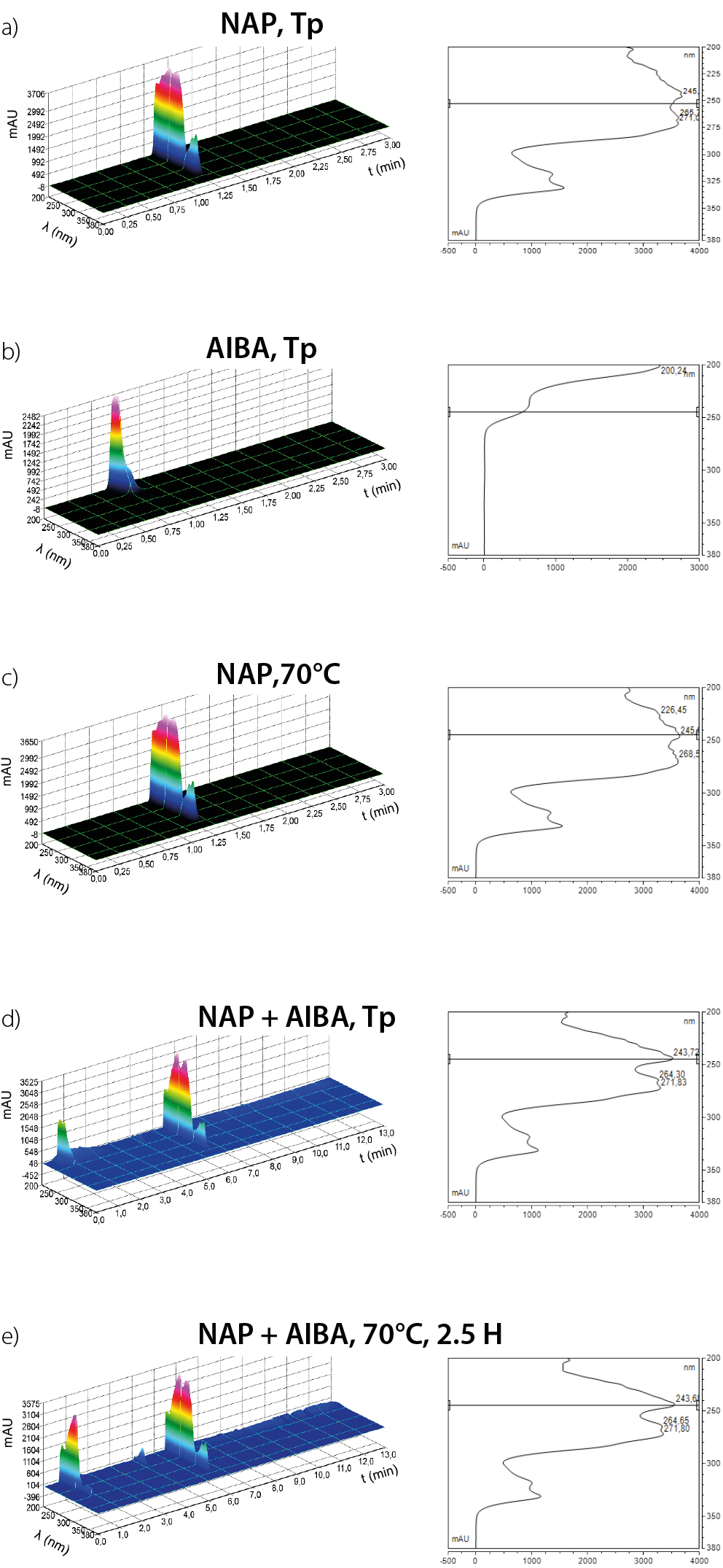

Aqueous solutions of NAP, AIBA and a NAP/AIBA mixture were analyzed using HPLC. Chromatographic analysis was conducted on samples prepared at room temperature and on samples subjected to 70°C for 2.5 h. Table 1 and Figure 1 show the retention times for the systems under examination.

The NAP chromatogram obtained at room temperature showed no new peaks, but a slight shift towards a higher retention time. This shift may be attributed to intermolecular interactions and subtle alterations in the analyte’s structure induced by elevated temperature. In aqueous media, NAP is susceptible to hydrolysis.19 However, at neutral or alkaline pH, the rate of hydrolytic degradation is relatively low.20 Nevertheless, an increase in temperature can facilitate hydrolysis. Furthermore, elevated temperatures can also induce the breakdown of the aromatic ring, but this process is significant at temperatures above 100°C.21 Moreover, a comparison of the chromatograms of NAP and AIBA to chromatogram of the NAP/AIBA mixture at room temperature revealed the absence of the NAP peak and the emergence of new peaks, indicative of NAP degradation or formation of new products. This observation suggests that NAP is unstable at room temperature in the presence of the radical initiator AIBA, even prior to radical formation. This behavior may indicate particular chemical interactions between NAP and AIBA, resulting in the formation of complexes or the initiation of a process by trace amounts of radicals. The formation of complexes between AIBA and NAP is theoretically possible. Some authors have used AIBA in synthesis, incorporating the drug into the polymeric matrix during the synthesis process. However, in this study, the direct potential interaction between AIBA and the drug was specifically evaluated.22 AIBA is a hydrophilic compound with 2 amide groups, capable of hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions in an aqueous environment. Moreover, in solution, AIBA can exist in an ionized form, consisting of chloride ions and protonated amide groups.

Naproxen sodium is a compound containing a carboxylate group (ionized in basic or neutral media) and an aromatic ring, enabling it to engage in both π–π interactions and hydrogen bonding. It can therefore be inferred that electrostatic interactions may occur between the ionized carboxylate group of NAP and the protic groups of AIBA.

It is also possible for a hydrogen bond to form between the amide group of AIBA and the carboxylate group of NAP. Furthermore, the aromatic ring of NAP may engage in hydrophobic interactions with non-polar AIBA fragments. As a polar solvent, water can solvate both AIBA and NAP, thereby reducing the likelihood of interactions between the two.

However, in the presence of ions (Cl– from AIBA or Na+ from NAP), specific complex interactions may take place. In contrast, the likelihood of trace amounts of AIBA radicals forming at room temperature is low, as their generation requires homolytic cleavage of the N=N bond at temperatures in the range of 60–80°C. Additionally, photochemical decomposition is a possible mechanism,23 but since the sample was not exposed to direct or prolonged UV radiation, this factor can be considered negligible.

Conclusions

The results suggest that NAP may not be a suitable candidate for incorporation during the polymerization process. Chromatographic analysis revealed the emergence of new peaks even at room temperature in the presence of AIBA, indicating NAP decomposition and the formation of new products. However, further research and additional experimental trials are required to gain a comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms and the processes involved.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.