Abstract

Background. The results of numerous research studies published in recent years suggest that celecoxib (CEL) may be effective in the treatment of various skin disorders. However, to date, no semisolid product containing CEL has been launched.

Objectives. With a focus on the future development of topical products, we aimed to investigate the impact of different semisolid matrices on the in vitro performance of CEL.

Materials and methods. For this purpose, 1% (w/w) of the drug was suspended in 4 compounding vehicles available in Polish community pharmacies: Lekobaza (amphiphilic cream), Lekobaza Lux (hydrophobic cream), Celugel (hydrogel), and Oleogel (lipogel). Given their very different physicochemical properties, our goal was to analyze, for the first time, their influence on spreadability, viscoelastic properties and the release rate of CEL.

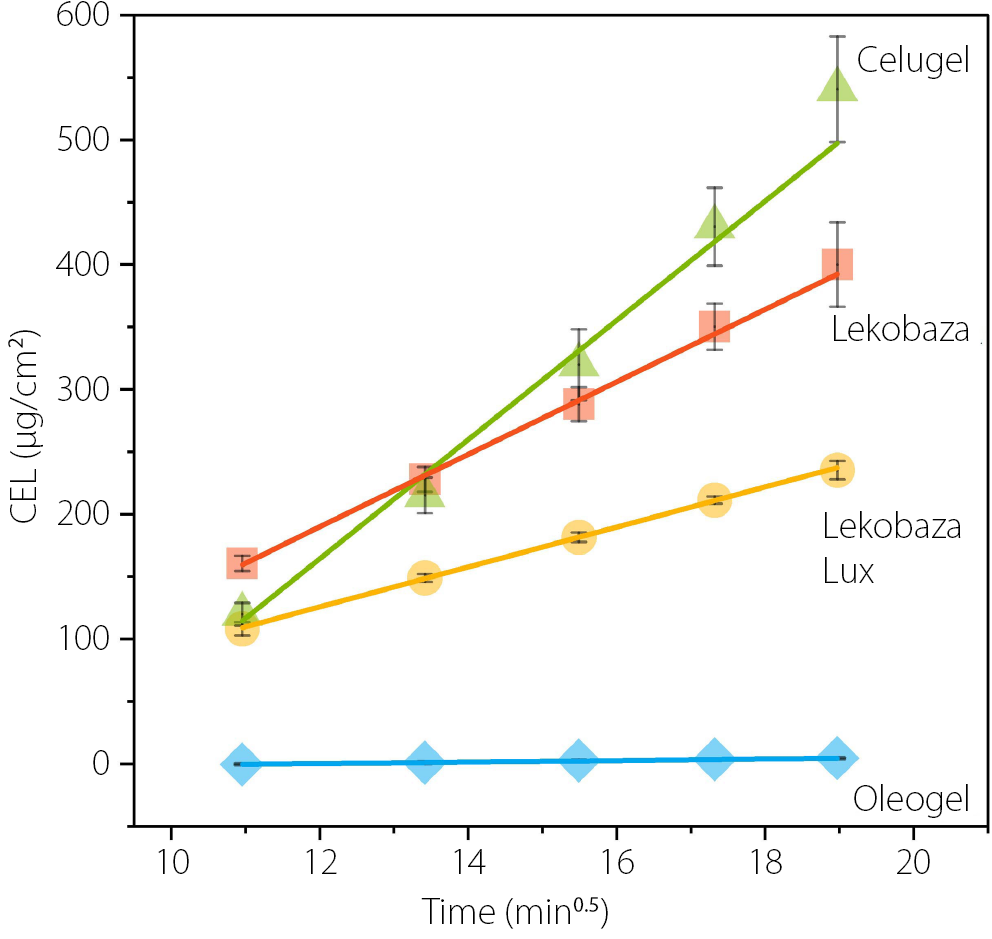

Results. It was found that all of the semisolid matrices were suitable as vehicles for the drug in terms of spreadability and rheological stability. The viscous properties predominated when Celugel was used as a vehicle, but when Lekobaza, Lekobaza Lux and Oleogel were tested, the elastic properties prevailed. The drug release rate was the highest when hydrophilic matrices, i.e., Celugel or Lekobaza were used, but when hydrophobic matrices such as Lekobaza Lux or Oleogel were examined, CEL was released slowly. These findings might be related not only to the properties of these matrices, but also to the design of the release study that was more suitable for evaluating the hydrophilic matrices.

Conclusions. Celugel could be particularly useful as a vehicle for CEL for the therapy of large lesions with heavy exudation, but if there is a risk of skin drying out after using the hydrogel, the use of Lekobaza can be recommended.

Key words: celecoxib, oleogel, hydrogel, cream, semi-solid drugs

Abstrakt

Wprowadzenie. Wyniki licznych badań naukowych opublikowanych w ostatnich latach, wskazują, że celekoksyb może być skuteczny w terapii chorób skóry. Jednak do tej pory nie wprowadzono do obrotu żadnego półstałego produktu leczniczego z celekoksybem.

Cel pracy. Myśląc o rozwoju półstałych produktów leczniczych z celekoksybem, przeznaczonych do podania na skórę, dokonano oceny wpływu, jaki rodzaj podłoża może mieć na właściwości aplikacyjne i uwalnianie substancji leczniczej w warunkach in vitro.

Materiał i metody. W tym celu 1% (w/w) celekoksybu zawieszono w czterech podłożach recepturowych, dostępnych w polskich aptekach, tj. Lekobaza (krem amfifilowy), Lekobaza Lux (krem hydrofobowy), Celugel (hydrożel) i Oleogel (lipożel). Ponieważ wykazują one bardzo zróżnicowane właściwości fizykochemiczne, po raz pierwszy dokonano oceny ich wpływu na rozsmarowywalność, właściwości lepkosprężyste i uwalnianie celekoksybu.

Wyniki. Stwierdzono, że wszystkie półstałe podłoża nadawały się jako nośniki leku pod względem rozsmarowywalności i stabilności reologicznej. Właściwości lepkie przeważały, gdy Celugel był używany jako nośnik, ale gdy testowano Lekobazę, Lekobazę Lux i Oleogel, przeważały właściwości elastyczne. Szybkość uwalniania celekoksybu była największa, gdy użyto hydrofilowe podłoża, takie jak Celugel lub Lekobazę, ale gdy badano matryce hydrofobowe, np. Lekobazę Lux lub Oleogel, uwalnianie celekoksybu następowało znacznie wolniej. Może to być związane nie tylko z właściwościami tych półstałych podłoży, ale także z metodyką zastosowaną w badaniach uwalniania. Była ona bardziej odpowiednia do oceny matryc hydrofilowych niż lipofilowych.

Wnioski. Podsumowując, Celugel może być szczególnie przydatny jako nośnik celekoksybu w leczeniu dużych zmian skórnych z silnym wysiękiem, ale jeśli istnieje ryzyko wysuszenia skóry po zastosowaniu hydrożelu, zalecane jest zastosowanie podłoża Lekobaza.

Słowa kluczowe: hydrożel, oleożel, celekoksyb, półstałe postacie leków, krem

Background

Celecoxib (CEL) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that selectively inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), reducing the production of prostaglandins. This effect contributes to its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties.1 Currently, the majority of drug products containing CEL are in the form of tablets and capsules, primarily used for the oral treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis symptoms in adults. The drug has also been approved for the oral treatment of dysmenorrhea and ankylosing spondylitis, an inflammatory condition affecting the joints and ligaments of the spine. In addition to these oral solid dosage forms, an oral solution of CEL for the treatment of acute migraine pain has also been introduced in recent years.2,3

On the other hand, numerous reports have highlighted serious side effects associated with oral systemic therapy using CEL. These reports prompted the exploration of new clinical indications, particularly for the topical treatment of inflammatory skin disorders or local infections. Nitescu et al. focused their research on the treatment of psoriasis.4,5 The authors developed ointments using white vaseline, in which 1%, 2%, 4%, or 8% of CEL was suspended. Using a mouse-tail model, Nitescu et al. demonstrated that CEL had a stronger anti-psoriatic effect than diclofenac, significantly increasing mean epidermal thickness4 and exhibiting anti-proliferative properties, particularly when the ointment contained 4% or 8% of the drug.5

The functionality of CEL was also studied in the treatment of hand-foot syndrome.6 This is a common chemotherapy side effect that manifests as burning pain, erythema, cracking of the skin, and blistering. A stable hydrogel containing carbomer (as a matrix-forming agent), glycerin, absolute ethanol, and PEG 400 was developed and evaluated in clinical studies. The patients applied a dose corresponding to half a teaspoon of CEL hydrogel to 1 extremity and the same amount of placebo hydrogel to the opposite extremity twice a day for 3 weeks. They were also instructed to apply a dose of Eucerin® cream 1 h after the hydrogel application, as the high ethanol content (33%) in the hydrogel could cause skin dryness. After this treatment, 60% of the patients showed at least 1 grade of improvement in their skin condition.6

Neelon et al.7 indicated that CEL’s anti-inflammatory properties might be a promising strategy to accelerate burn wound healing. The use of a carboxymethyl cellulose hydrogel loaded with 5 mg/mL of CEL resulted in a higher percentage of burn wound closure compared to 3 other anti-inflammatory agents tested in parallel.7 Interestingly, CEL also exhibits antimicrobial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). A significant reduction in the mean bacterial count was observed when a petroleum jelly loaded with 1% or 2% of the drug was applied to infected mice twice daily for 5 days.8

A review of the aforementioned research studies clearly demonstrates that semisolid matrices, whether hydrophilic or lipophilic, have been proposed as carriers for CEL in recent years. The choice of matrix depended on the availability of the carrier and the disease state of the skin. However, from both regulatory and technological perspectives, the type of semisolid matrix can significantly impact the ease of drug administration, usability and sensory feel (whether dry or greasy).9 Moreover, the rheological properties of the matrix influence the product’s texture and the drug release rate, which in turn affect the drug’s absorption through the skin, ensuring targeted efficacy

and safety.

Objectives

However, little is known about the impact that either hydrophilic or lipophilic semisolid matrices may have on CEL release. Therefore, the aim of this study is to assess how different semisolid matrices, destined for compounding and available in Polish community pharmacies (Table 1), may alter the spreadability, rheology and release rate of CEL. We believe that the results described in this study can serve as a starting point for the further development of new semisolid dosage forms loaded with CEL, tailored to specific clinical indications.

Materials and methods

Materials

Celecoxib was obtained from STI (Poznań, Poland). Celugel and Oleogel (Actifarm, Warsaw, Poland), and Lekobaza and Lekobaza Lux (Fagron, Cracow, Poland) were used as commercial semisolid bases. Polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG 400) was provided by Chempur (Piekary Śląskie, Poland). Acetonitrile (ACN) of chromatographic gradient grade was purchased from Witko (Łódź, Poland). Purified water was prepared using a Milli-Q Elix Essential water purification system by Millipore Corp. (Merck, Warsaw, Poland).

Manufacturing of semisolid formulations

Celecoxib (1% w/w) was suspended in 4 commercial semisolid compounding bases:

– Celugel (hydrogel; Actifarm, Warsaw, Poland);

– Lekobaza (amphiphilic cream; Fagron, Cracow, Poland);

– Lekobaza Lux (lipophilic polymeric cream; Fagron);

– Oleogel (lipogel; Actifarm, Cracow, Poland).

The formulations were prepared using an automatic compounding mixer, the Gako Cito-Unguator e/s (Eprus, Bielsko-Biała, Poland). The mixing time was set to 4 min, with the mixing speed set at 1,130 rpm (level 3). For Celugel, the drug was manually combined with the carrier using a pestle and mortar to avoid aeration of the final formulation.

Spreadability

A rectangular acrylic plate (4 mm-thick) with a central orifice of 1 cm in diameter was used as a template for applying samples. The template was placed on an acrylic support plate (20 cm × 20 cm) positioned on a millimeter scale. The sample was applied into the orifice of the template, and the surface was leveled with a spatula. After removing the template, the sample was covered with another acrylic plate of known weight (282 g), onto which weights of increasing mass were placed: 100 g, 200 g and 300 g. The radii of the surface onto which the formulations were spread were measured after 1 min of loading. The results were expressed as the mean area (n = 3) covered by the formulation. The test was carried out under ambient conditions.

Rheology

The viscoelastic properties were characterized using an oscillatory rheometer RS 6000 (Thermo-Haake, Karlsruhe, Germany) with parallel-plate geometry. The surface of both plates was roughened to ensure adhesion between the sample and the measuring plate. The samples were applied to the plate and left for 5 min in the measuring system for stress relaxation and temperature stabilization. Subsequently, the tests were performed at 25°C. The relationship between moduli and stress was measured from 1 to 1,000 Pa at a constant frequency of 1 Hz. The linear viscoelastic region (LVR) was determined using Haake Rheowin Data Manager v. 4.93 (Thermo-Haake) by the point at which the storage modulus (G') deviated by 5% from the plateau.10 The dynamic plastic stress (τ) was determined along with the corresponding deformation (γ). The mechanical spectra from 1 to 100 s⁻1 were recorded in the LVR at a constant deformation (γ = 0.01). The experimental data were described by power equations10:

where G' is the storage modulus (Pa), G" is the loss modulus (Pa), ω is the angular velocity (s⁻1), and K', K", n', n" are constants.

In vitro release test

Receptor solution screening

The in vitro release tests (IVRTs) were performed under sink conditions. Given that CEL is a poorly water-soluble drug, it was necessary to optimize the composition of the receptor solution. Preliminary research indicated that mixtures composed of 20–70% (v/v) ethanol 96°, 5% (v/v) PEG 400 and water were the most promising. The equilibrium solubility of CEL was determined at 32 ±1°C. An excess amount of the drug was added to 1 mL of the solvent mixture, and the samples were shaken at 500 rpm for at least 24 h to reach equilibrium (uniTHERMIX 2pro; Lab Logistics Group Labware, Meckenheim, Germany). Subsequently, they were centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 rpm (uniCFUGE 5; Lab Logistics Group Labware). After dilution and filtration, the concentration of CEL dissolved was quantified using a chromatographic method (see below). Finally, the mean values from 6 measurements were calculated.

Synthetic membrane screening

The screening of artificial membranes was conducted to select the barrier material that limits the diffusion of CEL the least. The porous artificial membranes (Ø = 0.45 μm) made of various materials, including hydrophobic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), hydrophilic polyethersulfone (PES), nylon (NY), and a dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cut-off of 14,000 Da (DIA), were tested. First, the binding of CEL to each of these membranes was analyzed. The membrane samples were immersed in 10 mL of CEL solution (20 μg/mL) in an aqueous-organic solvent mixture, chosen as the receptor solution for the IVRT. The samples were incubated at 32 ± 1°C for 12 h. After dilution, the concentration of CEL was quantified using a chromatographic method (n = 3).

Next, the release of CEL from a model formulation in Lekobaza was studied, with each of the aforementioned membranes placed between the donor and receptor chambers in a vertical diffusion cell (VDC). Prior to the IVRT, the membranes were presoaked for at least 12 h in either distilled water (for the DIA membrane to remove glycerol) or in the receptor solution (for PTFE, PES and NY). Further details on the test conditions are provided below.

Experimental design

The steady-state release of CEL from semisolid formulations was analyzed using a dry-heat Phoenix DB-6 six-cell manual sampling vertical diffusion system (Teledyne Hanson Research, Chatsworth, USA). The VDCs of size S, with an effective diffusional area of 1.0 cm2 and a receptor chamber capacity of 16.2 mL, were used in this study. A de-aerated aqueous-organic solution composed of ethanol 96°, PEG 400 and water (45:5:50, v/v) was applied as the receptor solution. The test was conducted at 32 ±1°C. The receptor phase medium was continuously stirred at 400 rpm using Teflon-covered magnetic stirring bars (15 × 6 mm). A 300 μL sample of the tested semisolid formulations was dosed onto the surface of a nylon membrane (Ø = 0.45 μm) in the donor compartment using a positive-displacement pipette (Microman E M1000E; Gilson, Villiers-le-Bel, France). Prior to assembly in the diffusion cell, the membranes were presoaked in the receptor solution for at least 12 h. The donor chambers were covered with glass covers to prevent the drying of the tested formulations. At predetermined time intervals (120, 180, 240, 300, and 360 min), 500 μL samples were withdrawn from the receptor compartment, and the volume was replaced with an equal volume of receptor solution preheated to 32°C. After dilution, the concentration of CEL released was quantified using a chromatographic method (see below).

For each cell, the amount of CEL released at each sampling time was determined in µg/cm2, and the mean cumulative amount released (n = 3) was plotted against the square root of time. According to the USP NF-PF monograph 〈1724〉 Semisolid Drug Products – Performance Tests, the slope of the resulting line serves as a measure of the release rate (steady-state flux).11

Quantification of celecoxib

The concentration of CEL released was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system (Agilent Technologies,Waldbronn, Germany) connected to a diode array detector (DAD). The separation of CEL was carried out with an InfinityLab Poroshell 120EC-C18 RP LC column (4.6 × 100 mm; particle size 4 μm; Agilent Technologies), along with the corresponding guard column. Prior to analysis, the samples were diluted with the mobile phase (1:1) and filtered through polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane filters (Ø = 0.22 μm). The injection volume was 20 µL.

A mixture of ACN and DMSO (9:1, v/v) was used as a needle wash solvent. The column temperature was set to 25°C. The mobile phase consisted of ACN and water (65:35, v/v), and the flow rate was maintained at 1.0 mL/min. CEL detection was performed at 254 nm. The CEL retention time was 2.80 min, and the total method run time was 3.50 min. A stock solution of CEL (1 mg/mL) in ACN was prepared and then diluted with the mobile phase (for equilibrium solubility studies) or with a 1:1 mixture of the mobile phase and the receptor solution (for IVRT) to obtain the corresponding calibration curves. The analytical method developed for equilibrium solubility studies was linear (r2 = 0.9999) within the concentration range of 0.2–12.0 µg/mL (LOD = 0.05 µg/mL, LOQ = 0.15 µg/mL), whereas for the IVRT test, it was linear (r² = 0.9999) within the concentration range of 2–80 µg/mL (LOD = 0.28 µg/mL, LOQ = 0.84 µg/mL).

Results

Spreadability

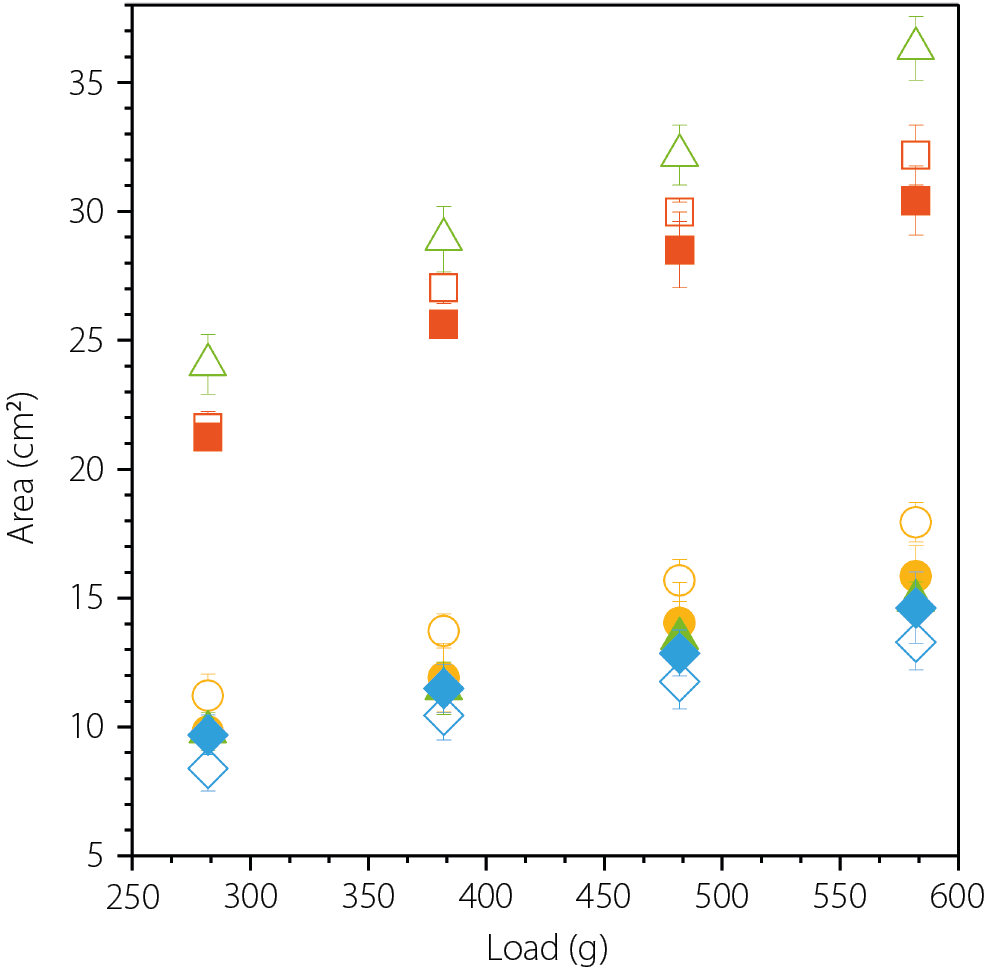

The spreadability of the tested formulations, expressed as the area covered by a known volume of the sample under a defined load, is shown in Figure 1. As a rule of thumb, the larger the area, the better the spreadability. Among the tested semisolid matrices, the greatest area was observed for the hydrogel Celugel and the amphiphilic cream base Lekobaza, measuring 36.3 ±1.2 cm2 and 32.2 ±1.2 cm2, respectively. When lipophilic matrices were analyzed, the area was approximately half that of the hydrophilic matrices, with 17.9 ±0.8 cm2 for Lekobaza Lux and 13.3 ±1.1 cm2 for Oleogel. Moreover, suspending 1% solid CEL particles in Lekobaza Lux resulted in a further reduction in spreadability (15.8 ±1.2 cm2), while the spreadability of Oleogel slightly improved (14.6 ±1.4 cm2). However, the most significant impact was observed with CEL in the hydrogel Celugel, where the drug-loaded formulation showed nearly twice lower spreadability, i.e., 14.9 ±0.9 cm2, compared to 36.3 ±1.2 cm2 for the blank formulation. These data points are not visible in Figure 1, as they are overlapped by those of Oleogel and Lekobaza Lux loaded with CEL. When CEL was suspended in the amphiphilic Lekobaza, the spreadability was only slightly reduced, with a final area of 30.4 ±1.4 cm2.

Rheological properties

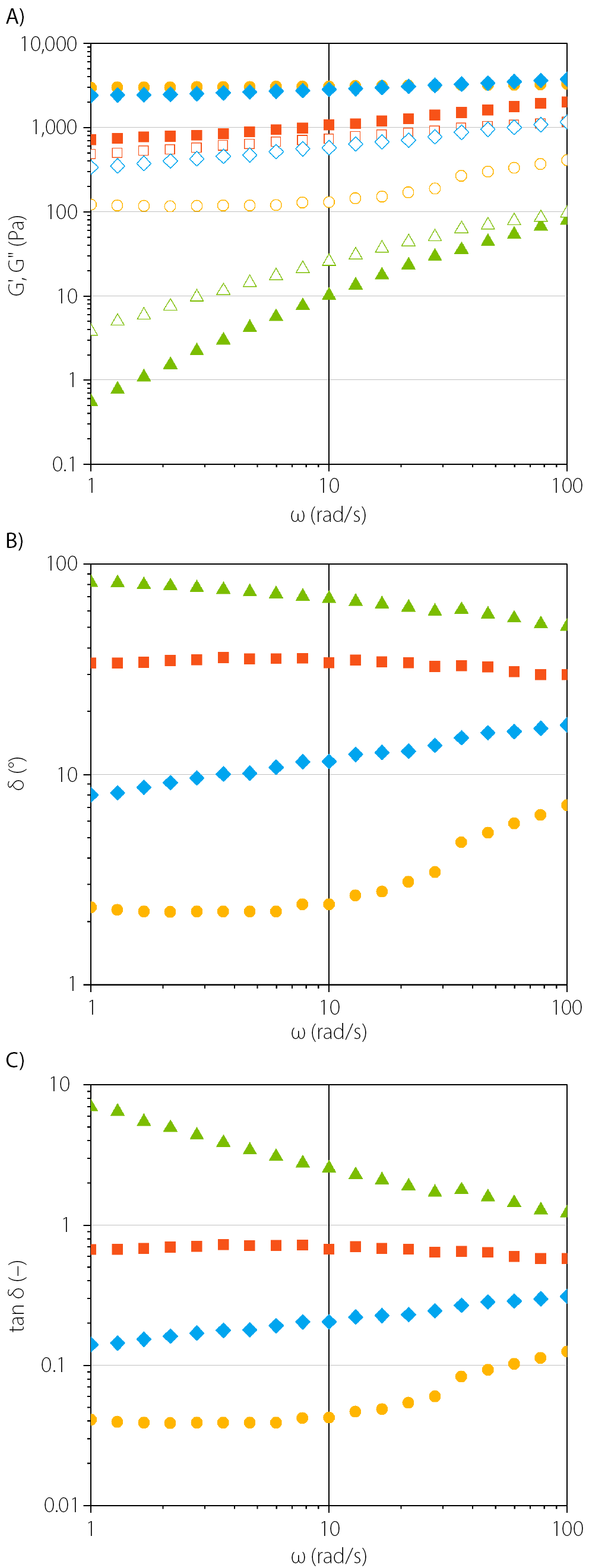

Oscillation frequency sweeps were performed to obtain information on the structural characteristics of semisolid formulations loaded with CEL, which may influence their functionality, drug release, and stability. In Figure 2A, the viscoelastic properties as a function of frequency are presented, using a fixed oscillation amplitude within the LVR, with the corresponding empirical power law fitting parameters provided in Table 2. Figure 2B and 2C display the values of phase shift angle (δ) and loss tangent (tan δ, the damping factor), respectively. The phase angle denotes the ratio of the loss modulus (G") to the storage modulus (G') and provides insight into the microstructure and overall viscoelastic properties of the material. A phase angle close to 0° indicates that the sample behaves as an ideal elastic solid, while a phase angle near 90° suggests it behaves as a viscous liquid.12 For all examined formulations loaded with CEL, the phase angle ranged between 2° and 82°, which indicates that their rheological properties are suitable (0–90°) for spreading on the skin surface (Figure 2B).

In the Celugel formulation loaded with CEL, the viscous characteristics predominated (G' < G", Figure 2A & tan δ = 1.2–6.9). Both the storage and loss moduli increased with increasing frequency until the crossover point (G' = G") at approx. 100 rad/s, indicating that the hydrogel behaves as a viscoelastic liquid. In contrast, the CEL formulation in Oleogel exhibited viscoelastic solid behavior (G' > G"), with high storage modulus (G') values that remained nearly constant across the entire frequency range, while the loss modulus (G") gradually increased. Similarly, the Lekobaza Lux formulation loaded with CEL showed a predominant storage modulus (G'>> G") and exhibited the highest values among all tested formulations. Like Oleogel, the storage modulus remained almost constant across the entire frequency range. The constant G’ values indicate that the formulation has a rigid structure with a yield point that was not exceeded under the applied frequency range. When the suspension of CEL in Lekobaza Lux was analyzed, the loss modulus (G") remained constant at low frequencies, approx. 4 times lower than that of Oleogel, but began to increase when the angular velocity (ω) exceeded 10 rad/s. This suggests a transition from elastic gel-like behavior (G' > G") to more viscous characteristics (viscoelastic solid). However, a crossover point was not observed. For Lekobaza loaded with CEL, the elastic properties dominated (G' > G"), and both moduli gradually increased with increasing frequency. The difference between the elastic modulus (G') and the viscous modulus (G") was the smallest among all the formulations tested.

Overall, the higher values of the storage modulus compared to the loss modulus (G' > G" & tan δ < 1) in CEL formulations in Lekobaza, Lekobaza Lux and Oleogel are considered favorable. These results indicate that cohesive forces predominate in these systems, reducing the risk of the drug dose dripping off the skin.13 Since the loss tangent values reflect the strength of the particle association in the polymeric network, it can also be concluded that, upon storage under resting conditions (mimicked by the lowest frequency of 1 rad/s), these 3 formulations exhibited the lowest tan δ (Table 2, Figure 2C), suggesting the strongest particle association at the microstructural level. This may ensure high long-term stability by reducing the risk of phase separation in the dense matrix.12

Design of IVRT

Since CEL is primarily administered orally, no compendial test exists for studying its release from semisolid matrices. Consequently, the present study began with the search for both an appropriate receptor solution and an artificial membrane to establish the conditions for IVRT. These conditions were then used to evaluate the performance of the developed topical formulations.

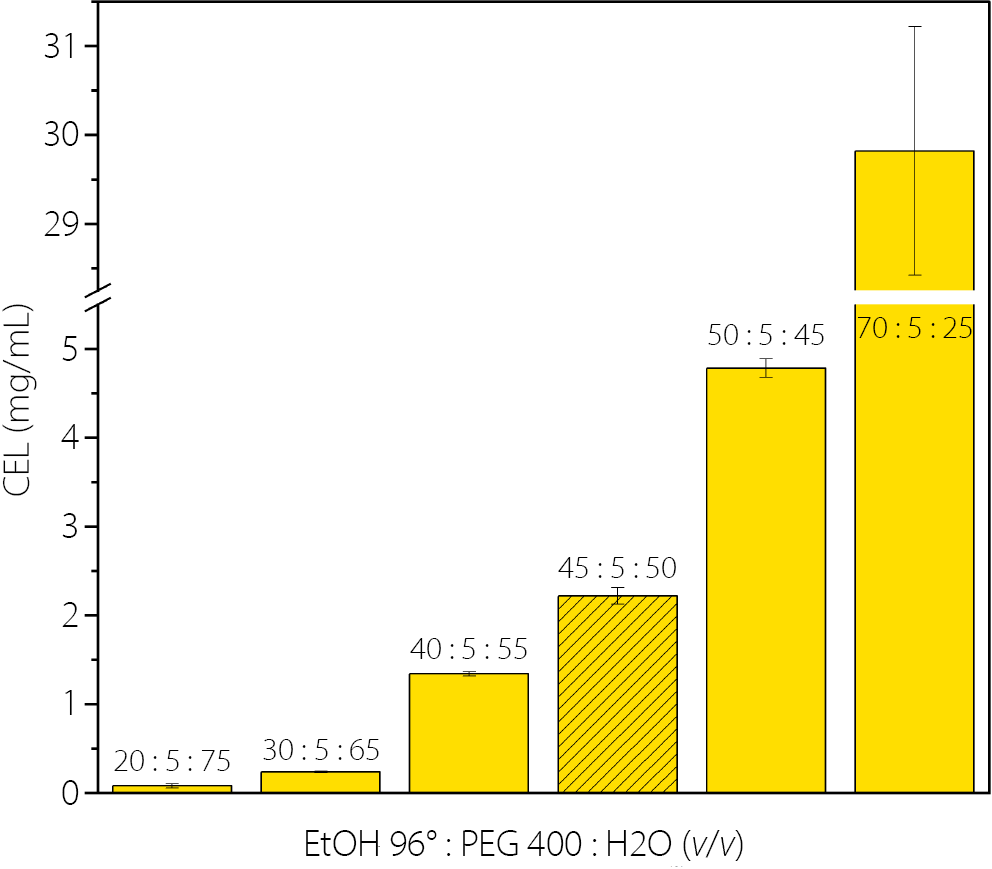

Given the poor solubility of CEL in water (<5 μg/mL), an aqueous-organic mixture was required as a receptor solution to maintain sink conditions. Based on published data and our preliminary solvent screening (data not shown), a mixture composed of water, ethanol 96° and PEG 400 was selected as the most promising. The PEG 400 concentration was kept at 5% (v/v). The effect of various ethanol 96° concentrations was evaluated to determine the optimal solvent ratio that ensures the highest equilibrium solubility of CEL. As shown in Figure 3, drug solubility increases gradually with the concentration of ethanol 96°. However, a high concentration of ethanol in the receptor solution could potentially lead to backward diffusion into the donor chamber and may affect the integrity of the membrane. To minimize these risks, it is important to keep the ethanol concentration as low as possible. Therefore, a mixture composed of 45% ethanol 96°, 5% PEG 400 and 50% water was selected for IVRT studies. The equilibrium solubility of CEL in this mixture at 32°C was 2.2 ±0.09 mg/mL.

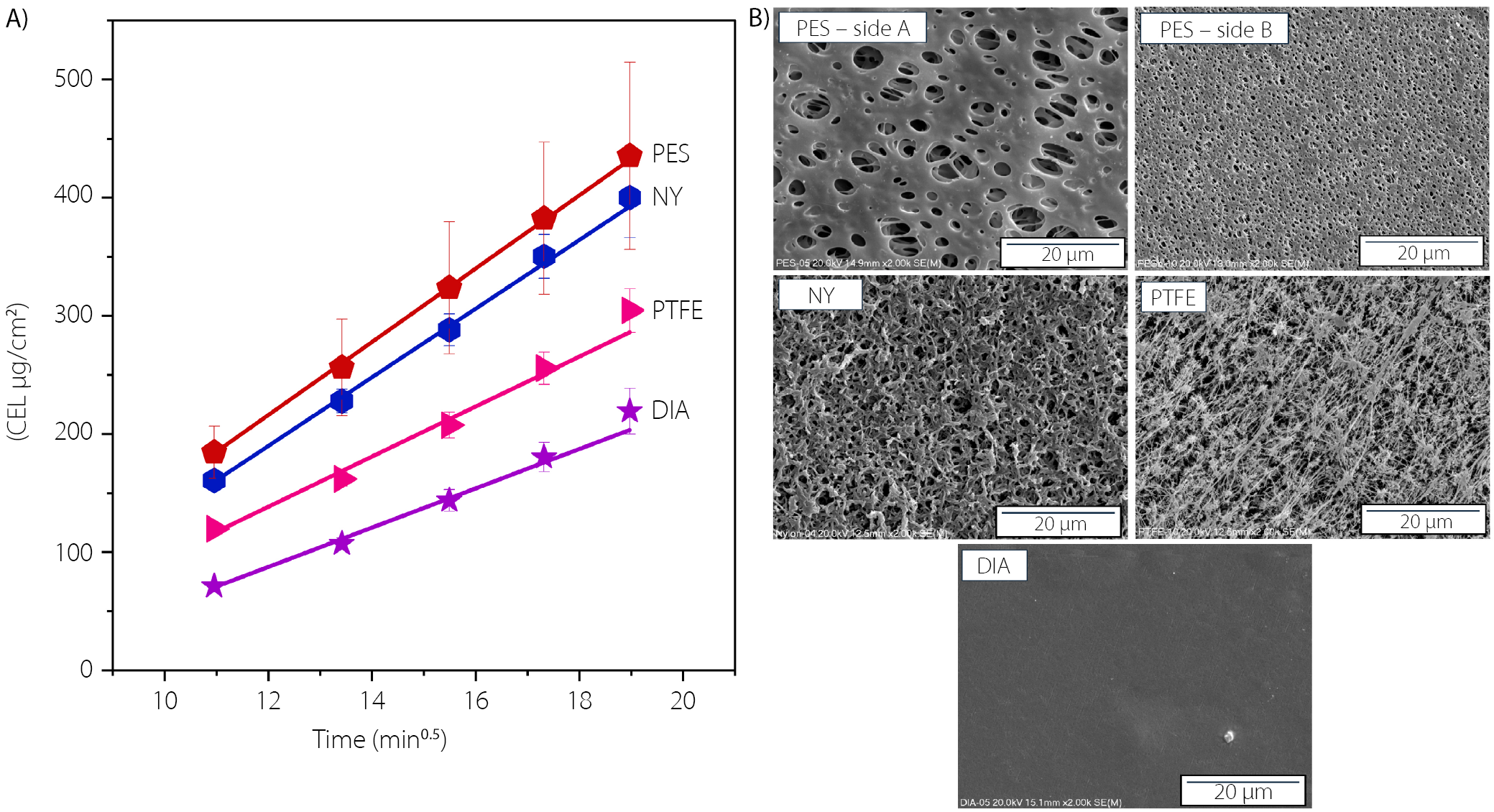

The suitability of 4 synthetic filter membranes (0.45-µm pore size) for the IVRT of CEL was also assessed. Initially, the binding of CEL was evaluated by measuring the recovery after soaking the membranes for 12 h in the drug solution. The recovery ranged from 99.0% to 100.7%, confirming that all membranes met the guidelines for inertness.14 Next, the impact of the filter material on the diffusion of CEL suspended in the semisolid matrix was investigated to select the material that least hindered this process. Based on screening tests showing a high drug diffusion rate from Lekobaza, this semisolid matrix was selected as the model for this part of the study. The release profiles obtained (using the receptor solution of the previously described composition), along with scanning electron micrographs of the membrane surface, are presented in Figure 4A and Figure 4B, respectively. The corresponding linear regression parameters are provided in Table 3. With the exception of the PES membrane, all studied filters exhibited symmetry in terms of pore size. For the PES membrane, the side with the largest pores (side A) was oriented towards the donor cell, while the side with the smallest pores (side B) faced the receptor cell (Figure 4B). As shown in Figure 4A, drug diffusion was least restricted when PES and NY membranes were used. The difference between the slopes for these membranes was minimal (31.00 ±0.44 vs 29.03 ±0.70), but the variation in CEL concentration released across the cells was significantly lower when the NY membrane was used instead of PES. Considering the low binding of CEL to the NY membrane (recovery of 99.8%), the high compatibility of this membrane with both the receptor solution and semisolid formulations, as well as the reduced variability in CEL diffusion, the NY membrane was selected to evaluate the performance of CEL in various semisolid matrices.

Impact of semisolid matrix on CEL release

In Figure 5, the cumulative amount of CEL released from the developed semisolid formulations is plotted against the square root of time. The slope of this line represents the drug release rate (Table 3).11 All formulations exhibited a linear relationship between the amount of drug released and the square root of time, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.98. This confirms that CEL release follows the Higuchi model, indicating that the release process is diffusion-controlled. After 6 h, the highest amount of CEL was released from the hydrophilic Celugel (540.5 ±42.3 μg/cm2), followed by the amphiphilic Lekobaza (399.9 ±33.8 μg/cm2). The CEL release from the lipophilic Lekobaza Lux (235.3 ±7.3 μg/cm2) was nearly half that of the release from Lekobaza. When the CEL suspension in a lipophilic Oleogel matrix was studied, the amount of CEL released remained very low, even after 6 h of testing (4.6 ±0.5 μg/cm2), which was more than 100 times lower compared to Celugel. These results were reflected in the slope values, which followed this order: Celugel > Lekobaza >> Lekobaza Lux >>> Oleogel. This clearly indicates that the drug’s affinity to the semisolid matrix and the receptor solution governs the kinetics of CEL partitioning. Since CEL is a lipophilic drug (logP = 3.53), it has a strong affinity for lipophilic vehicles, resulting in slower release rates as the lipophilicity of the matrix increases, especially when a hydrophilic receptor solution is used. Similar findings were reported by Shah et al.,15 who optimized the IVRT conditions for hydrocortisone (logP = 1.61) using phosphate buffers as receptor solutions. They showed that the IVRT results correlated well with the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic response when hydrophilic semisolid matrices (e.g., lotions, creams) were used as drug vehicles. However, when hydrocortisone was incorporated into a lipophilic matrix, its diffusion to the receptor solution was highly limited, and this did not correlate with the in vivo performance of the drug. To address this challenge, the authors demonstrated that saturating the synthetic membrane with a 15% solution of ethoxylated aliphatic amine in isopropyl myristate (mimicking the lipids of the skin) was critical to enhance the miscibility of the receptor solution with the matrix components. This approach led to reliable in vitro results that better reflected the in vivo performance of the drug when topical oily vehicles were used.15 In the present study, Oleogel was the most lipophilic semisolid matrix among the tested vehicles. This vehicle is immiscible with the receptor solution, which could hinder the partitioning of CEL between the matrix and the receptor solution, especially when separated by a hydrophilic synthetic membrane. A similar observation can be made for CEL release from Lekobaza Lux (lipophilic cream). The release rate was approx. twice as slow compared to when the amphiphilic cream, Lekobaza, was used.

However, the advantages of using hydrophilic matrices, such as emulgels or hydrogels, over lipophilic ointments for the cutaneous delivery of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac sodium were demonstrated by Manian et al.13 Diclofenac sodium, with a similar logP of 4.26 to CEL, is sparingly soluble in water, in contrast to the practically insoluble CEL. The authors found that the release rate of diclofenac sodium was the fastest from the hydrogel and the slowest from the ointment. Similar to our approach, they did not saturate the synthetic membranes with isopropyl myristate. Interestingly, their IVPT studies on human skin provided evidence that the drug permeability was greatest from the emulgel, followed by the emulsion and the hydrogel. Notably, there was no permeation of the drug from the ointment.

These results suggest that hydrophilic vehicles, which are non-greasy and thus more acceptable to patients, could be more favorable than lipophilic matrices for topical CEL delivery. A proper design of IVRT, including the saturation of the synthetic membrane with a solvent mimicking skin lipids, seems crucial when analyzing lipophilic matrices in order to obtain reliable in vivo performance insights into the performance of poorly soluble drugs based on in vitro results. This approach will be explored in detail in our future studies.

Limitations

Taking into account the variety of new indications for celecoxib, e.g. oncological therapy, psoriasis treatment or its antimicrobial activity, the use of semisolid carriers that differ a lot in properties is proposed. However, comparing in vitro is challenging, and does not always reflect the ease of administration or therapeutic effects observed upon topical treatment. Among others, this applies to release studies (IVRT), where a design of the test in terms of the kind of a diffusion chamber, an artificial membrane, a contact area or a receptor solution can have an impact on the final results, and therefore; its combination with IVPT, microscopy and spectroscopy is necessary to better characterize in vitro a new semisolid product.

Conclusions

The choice of semisolid matrix significantly influences the spreadability, rheology and release rate of suspended CEL. Among the developed formulations, the greatest spreadability was observed when Lekobaza was used, while Oleogel exhibited the smallest spreadability. Rheological measurements indicated that all samples exhibited non-Newtonian fluid characteristics with shear-thinning properties. The comparison of oscillation frequency sweep profiles revealed that the viscous component predominated only when Celugel was used as a vehicle. When CEL was suspended in Oleogel, Lekobaza or Lekobaza Lux, the elastic properties prevailed. Despite the differences in the viscoelastic properties of the developed formulations, all of them exhibited rheological properties suitable for topical administration. The low tan δ values typical of Oleogel, Lekobaza and Lekobaza Lux suggest their high long-term stability. The rheology and lipophilicity of the matrix influenced the CEL release rate. The drug was released rapidly from the hydrophilic Celugel matrix, which exhibited viscous liquid characteristics. However, when the formulation made with Oleogel was tested, the lack of miscibility between the matrix and the receptor solution likely hindered drug diffusion. Therefore, the design of the IVRT test, particularly for poorly soluble drugs, should ensure optimal miscibility between matrix components and the receptor solution. The IVRT study design outlined in this research appears to be the most suitable for evaluating CEL release from hydrophilic matrices. From a clinical perspective, hydrogels are recommended for the treatment of inflammatory skin lesions with exudate, making Celugel a suitable vehicle for CEL. However, if there is a risk of skin drying due to chronic treatment, the formulation of CEL in Lekobaza cream appears to be the better option. This is particularly relevant as the high spreadability of CEL suspended in Lekobaza makes it ideal for application over large skin surfaces.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.