Abstract

Background. Polyhydroxybutyrate nanoparticles (PHB-NPs) represent a promising strategy for addressing the growing threat of bacterial resistance to antibiotics – a major concern in global public health. Despite their potential, there is a noticeable gap in the current literature regarding their ability to enhance the efficacy of existing antibiotic therapies.

Objectives. This study investigates the synergistic effect of PHB-NPs in enhancing the antibacterial activity of ceftriaxone (CRO) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with a particular focus on mitigating key virulence factors such as biofilm formation and adhesion.

Materials and methods. Polyhydroxybutyrate nanoparticles were synthesized using the pH gradient and sonication method. The antibacterial activity of PHB-NPs, CRO and the combined formulation (PHB-NP-CRO) was assessed using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing and the well diffusion method. Additionally, the effects of these formulations on P. aeruginosa biofilm formation on an abiotic surface (polystyrene) and bacterial adhesion to human oral mucosal epithelial cells (OMECs) were evaluated.

Results. The diameters of the prepared PHB-NPs ranged from 15 nm to 34 nm, with an average size of 28.2 ±6.3 nm. All P. aeruginosa isolates were capable of biofilm production. A negative correlation was observed between the diameter of the CRO inhibition zones and the extent of biofilm formation among the 20 isolates. The MICs for PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, and the combined formulation (PHB-NP-CRO) were 2,000, 1,000, 250, and 62.5 µg/mL, respectively. Sub-MIC concentrations (as low as 1/32 MIC) of both CRO and PHB-NP-CRO exhibited significant inhibitory effects on biofilm formation and bacterial adhesion to human OMECs (p < 0.050).

Conclusions. The combination of PHB-NPs with CRO significantly enhances the antibacterial activity of CRO against P. aeruginosa. Moreover, sub-inhibitory concentrations (sub-MICs) of both PHB-NP-CRO and CRO alone effectively reduce the bacterium’s ability to form biofilms and adhere to biotic surfaces.

Key words: nanoparticles, adhesion, biofilm, ceftriaxone, polyhydroxybutyrate

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen that poses a significant threat to public health. It is known for causing a wide spectrum of infections, ranging from relatively mild skin and soft tissue infections to life-threatening conditions such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, otitis media, bloodstream infections, and sepsis.1, 2, 3, 4

The ability of P. aeruginosa to form biofilms, its intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics and its capacity to acquire additional resistance mechanisms through genetic adaptation represent key virulence factors of this bacterium.1, 2, 3 These characteristics make P. aeruginosa infections particularly challenging to treat, especially in immunocompromised patients.5 One of the primary strategies for eradicating P. aeruginosa infections involves the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Ceftriaxone (CRO), a third-generation cephalosporin, is among the agents that may be employed. It acts by inhibiting bacterial cell wall synthesis.3 However, the emergence of antibiotic resistance – particularly resistance to cephalosporins – poses a significant concern in the treatment of P. aeruginosa infections. Resistance can occur through various mechanisms, including the secretion of β-lactamases that hydrolyze the β-lactam ring of CRO, alterations in bacterial cell wall permeability and overexpression of efflux pumps.6 Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop strategies that enhance the antibacterial efficacy of existing antibiotics – especially in light of the rising prevalence of antibiotic resistance and the limited success in discovering new antimicrobial agents. Nanotechnology offers promising strategies to address the growing challenge of antibiotic resistance. Nanomaterials can enhance drug delivery, improve antibiotic efficacy and help overcome bacterial resistance mechanisms. Among the various nanomaterials explored, polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) nanoparticles have emerged as a biocompatible and biodegradable option for advanced drug delivery systems.7

Polyhydroxybutyrate is considered a low-toxicity material, primarily due to its natural biodegradability, biocompatibility and non-toxic degradation products. It is a naturally occurring polyester synthesized by various microorganisms, including Ralstonia eutropha and Bacillus species.8 Numerous previous studies have explored the antibacterial properties of PHB. As a naturally occurring polyester synthesized by microorganisms, PHB is particularly attractive due to its low toxicity.9 Previous studies have demonstrated the antibacterial activity of polyhydroxybutyrate nanoparticles (PHB-NPs) against various bacterial species. Additionally, other researchers investigated the efficacy of CRO in treating burn wound infections caused by P. aeruginosa.9, 10, 11

Rossi et al. incorporated polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) with gentamicin for the treatment of Staphylococcus infections.12 An earlier study demonstrated that sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MICs) of CRO reduced P. aeruginosa adhesion to human oral mucosal epithelial cells (OMECs).3 However, the antibacterial effect of combining PHB-NPs with CRO remains scarcely explored in the literature.

Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the potential of PHB-NPs loaded with CRO to enhance the antibiotic’s efficacy against P. aeruginosa in vitro. The current research may contribute to the development of novel therapeutic strategies for combating drug-resistant P. aeruginosa infections and improving patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Human Ethical Committee of the Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Baghdad, Iraq. An official signed approval letter was issued under Reference No. CSEC/1124/0098 on June 8, 2024.

Isolation and identification of bacteria

Infected wound samples were aseptically collected from 91 inpatients diagnosed with wound infections at Baghdad Teaching Hospital (Baghdad, Iraq). All patients had not received antibiotic treatment within 72 h prior to sample collection and provided written informed consent to participate in the study. Wound swabs were cultured on MacConkey agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) and incubated at 37°C for 18 h.

Non-fermenting colonies were sub-cultured onto cetrimide agar (HiMedia) for further identification. Colonies exhibiting bright fluorescent green pigmentation – attributed to pyoverdine production – with flat, spreading morphology and a smooth, mucoid texture were selected for analysis. Standard biochemical tests were performed to identify the clinical isolates. Final identification of P. aeruginosa was carried out using the VITEK® DensiCHEK™ instrument and fluorescence-based system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) with the ID-GNB identification card.

PHB-NPs preparation

Polyhydroxybutyrate nanoparticles were prepared and characterized following the method previously described by Ghafil and Flieh.13 Briefly, 0.5 g of PHB (Sigma-

-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was dissolved in 25 mL of distilled water, and the pH was adjusted to 4 using 1 N HCl. The mixture was subjected to ultrasonication at 4,500 kHz for 30 s at 21°C. Subsequently, the pH was raised to 10 using 1 N NaOH. The solution was then shaken in a water bath shaker (Memmert GmbH, Schwabach, Germany) at 37°C for 2 h and incubated at 21°C for 18 h.

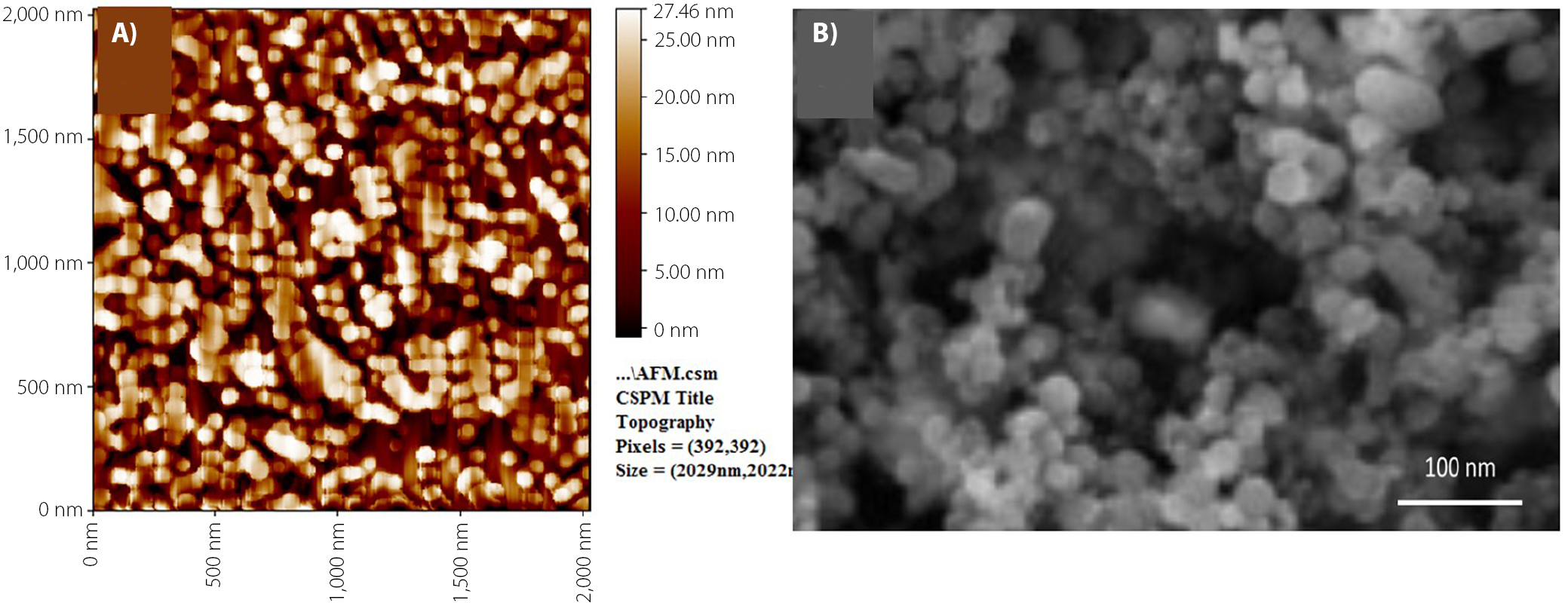

Following incubation, the pH of the solution was readjusted to 7 using 1 N HCl. The prepared PHB-NPs were characterized using atomic force microscopy (AFM; Innova® AFM; Bruker, Santa Barbara, USA). For AFM analysis, a thin film of the nanoparticles was deposited on a silica glass plate. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was also performed (Zeiss EVO® LS 15; Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany); a glass smear of the PHB-NPs was prepared and coated with a thin layer of platinum to enhance conductivity for imaging.13

Kirby–Bauer method

The Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method was employed to assess the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to CRO. A bacterial suspension adjusted to a turbidity equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard was uniformly spread onto Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plates (20 mL per plate; HiMedia). Ceftriaxone disks (30 µg; Bioanalyse, Ankara, Turkey) were placed on the surface of the agar, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h.

The diameters of the inhibition zones around each CRO disk were measured and interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoint guidelines. Based on these standards, isolates were classified as sensitive (S), intermediate (I) or resistant (R). Notably, resistance classification was determined for CRO.14

Minimum inhibitory concentration

The microdilution technique described by Al-Mutalib and Zgair,15 was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, and PHB-NPs-CRO against a P. aeruginosa strain exhibiting high resistance to CRO. Stock solutions of PHB and PHB-NPs (5 mg/mL) were prepared by dissolving 0.5 g of each in 100 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Equivalent concentrations of CRO and PHB-NPs-CRO (containing 1 mg PHB-NPs and 1 mg CRO) were used for MIC determination.

Double-fold serial dilutions (100 μL) were prepared in a 96-well U-bottom microtiter plate (BIOFIL) using sterile Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB; HiMedia). The P. aeruginosa suspension was prepared by harvesting overnight bacterial growth, followed by washing with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.1 M, pH 7.2) and centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA). The optical density (OD) of the resulting suspension was adjusted to 0.1 at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer (Bioevopeak, Jinan, China).

The microtiter plates were gently shaken and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Multiple controls were included in the experiment: 1) MHB with the bacterial isolate, 2) MHB only (sterility control), 3) serial dilutions of PHB, 4) serial dilutions of PHB-NPs, 5) serial dilutions of CRO, 6) serial dilutions of PHB-NP-CRO, and 7) serial dilutions of DMSO. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration of the tested compound that completely inhibited visible bacterial growth.15

Well diffusion method

The method described by Hasan and Ghafil16 was followed to evaluate the antibacterial effects of PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, and PHB-NPs-CRO against P. aeruginosa strain Pa11. A 100 μL aliquot of the standardized Pa11 inoculum (OD₆₀₀ = 0.1), as prepared in section of MIC method, was uniformly spread onto MHA plates.

Five wells, each 8 mm in diameter, were created in the agar using a sterile cork borer. Each well was filled with 100 μL of the respective test solution (2,000 μg/mL) of PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, or PHB-NPs-CRO. One well was filled with 100 μL of DMSO and served as a negative control. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. The diameters of the inhibition zones around each well were measured using a ruler. All experiments were performed in triplicate.16

Biofilm formation

The standard method described by Talib and Ghafil3 was followed to assess biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa strains resistant to CRO (30-µg disk). Briefly, 200 μL of sterile Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB; HiMedia) were added to the wells of a flat-bottom polystyrene tissue culture plate. A 5 µL aliquot of the standardized P. aeruginosa inoculum (prepared as described in MIC method) was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. After incubation, the TSB was discarded, and the wells were gently washed 3 times with sterile distilled water to remove non-adherent cells. The plates were air-dried and stained with 200 μL of 0.4% Hucker’s crystal violet solution for 15 min. Excess stain was removed by washing the wells 5 times with distilled water. After complete drying, 200 μL of anhydrous ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the bound dye. The absorbance was measured at 590 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek 800 TS; BioTek, Winooski, USA). The experiment was performed in triplicate.3 To investigate the effect of various sub-MIC concentrations of PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, and PHB-NPs-CRO (½ MIC, ¼ MIC, ⅛ MIC, ¹⁄₁₆ MIC, ¹⁄₃₂ MIC, and ¹⁄₆₄ MIC) on P. aeruginosa biofilm formation, a modification of the standard biofilm assay was employed. Instead of using plain TSB, serial dilutions of each test compound at the indicated sub-MIC levels were prepared in TSB (HiMedia) and added to the wells of a flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plate. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h, after which the wells were washed 3 times with distilled water to remove non-adherent cells. The wells were then stained with 200 μL of crystal violet (0.4%) for 15 min. After thorough washing and air drying, 200 μL of anhydrous ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the bound dye. The absorbance was measured at 590 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek 800 TS). The experiment was performed in triplicate.3

Effect of sub-MICs on adhesion to human OMECs

In this experiment, a P. aeruginosa strain that exhibited resistance to CRO 30-μg antibiotic disk and produced the highest level of biofilm was selected to study the effect of various sub-MICs of PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, and PHB-NPs-CRO (½ MIC, ¼ MIC, ⅛ MIC, 1⁄16 MIC, ¹⁄₃₂ MIC, and ¹⁄₆₄ MIC) on bacterial adhesion to human OMECs. Previously established methods were followed to culture human OMECs in vitro and to assess the influence of different antibiotic concentrations on P. aeruginosa adhesion to these cells.3,15

Bacterial colonies were cultured in TCB (HiMedia). A standardized inoculum of P. aeruginosa (OD₆₀₀ = 0.1) was prepared in TSB and treated with various sub-MICs (½ MIC, ¼ MIC, ⅛ MIC, 1⁄16 MIC, ¹⁄₃₂ MIC, and ¹⁄₆₄ MIC) of PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, and PHB-NPs-CRO. The suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. After incubation, the bacterial cultures were washed 3 times with PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2) by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting bacterial pellets were resuspended in fresh TSB, and the optical density was readjusted to 0.1 at 600 nm. In tissue culture tubes (Biofil, Guangzhou, China), 900 μL of a suspension containing 1 × 10⁵ human OMECs in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 10 mM L-glutamine was mixed with 100 μL of pre-treated P. aeruginosa (OD₆₀₀ = 0.1). The tubes were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Following incubation, the OMECs were washed 3 times with PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2) by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 8 min (Beckman Coulter) to remove non-adherent bacteria. One portion of the OMECs was stained with Leishman’s stain for microscopic examination. The remaining cells were lysed using PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). The resulting lysate was serially diluted tenfold and plated on nutrient agar to enumerate viable adherent bacteria. The OMECs exposed to untreated bacteria to PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, and PHB-NPs-CRO served as control groups.3,15

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed and graphs generated using Origin pro 8.6 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA). Data are presented as means ± standard error (M ±SE). Differences between groups were evaluated using Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Correlations were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PHB-NP preparation

In the present study, PHB nanoparticles (P3HB-NPs) were prepared using the pH gradient combined with ultrasonication, which proved to be the most effective method for producing uniform nanoparticles. To confirm the nanoparticulate nature of the prepared material, ATM and SEM were employed, as illustrated in Figure 1. The results indicated that the diameters of the synthesized PHB-NPs ranged from 15 nm to 34 nm, with an average size of 28.2 nm.

Bacterial isolates

Twenty P. aeruginosa isolates were obtained from 91 wound swab samples collected from inpatients with severe wound infections. Initial identification was performed using microscopic examination and standard biochemical tests, followed by confirmation with the VITEK 2 system (bioMérieux). Findings indicate a high prevalence of P. aeruginosa in wound infections, with an isolation rate of 21.97%.

Antibiotic susceptibility and biofilm formation

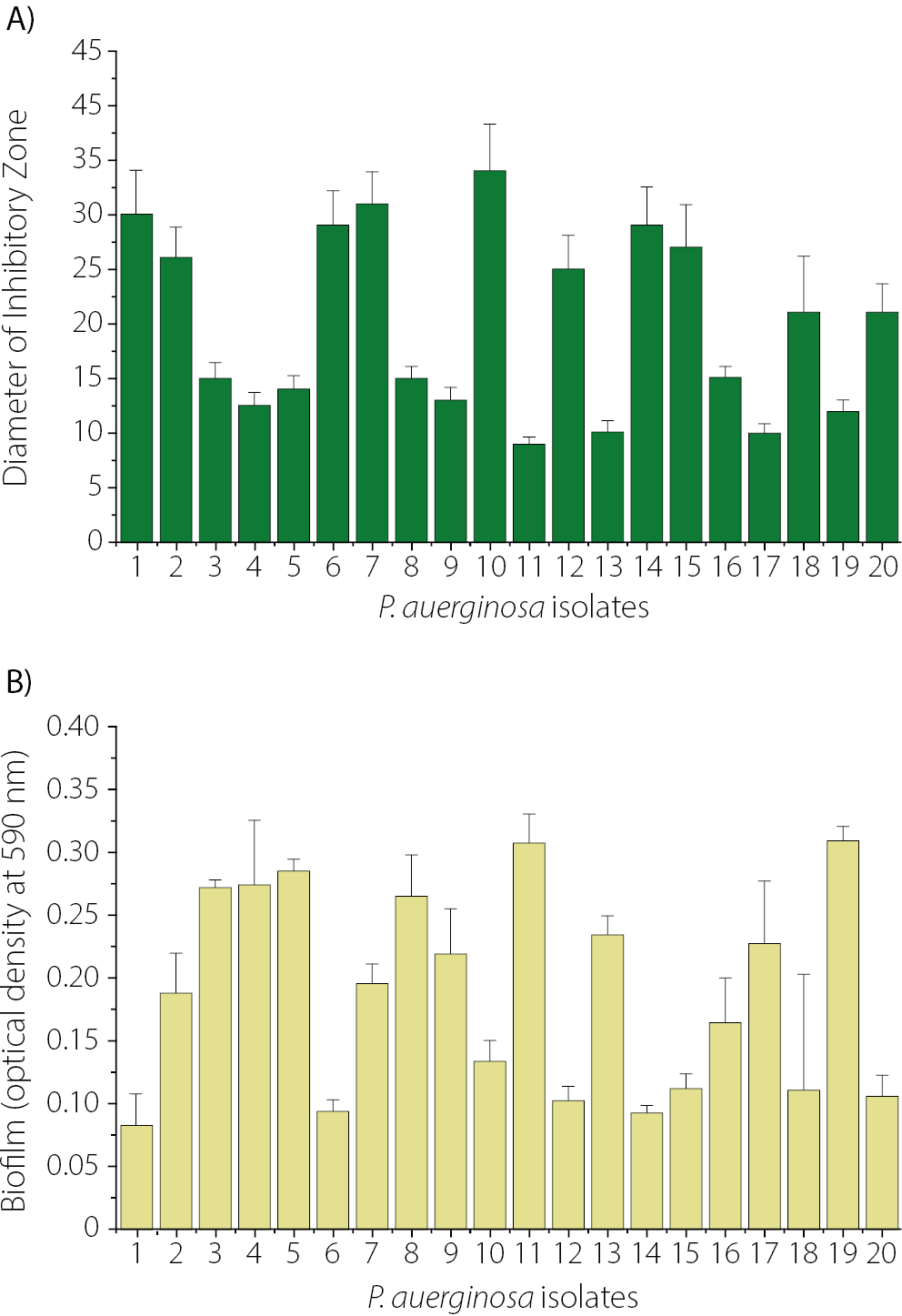

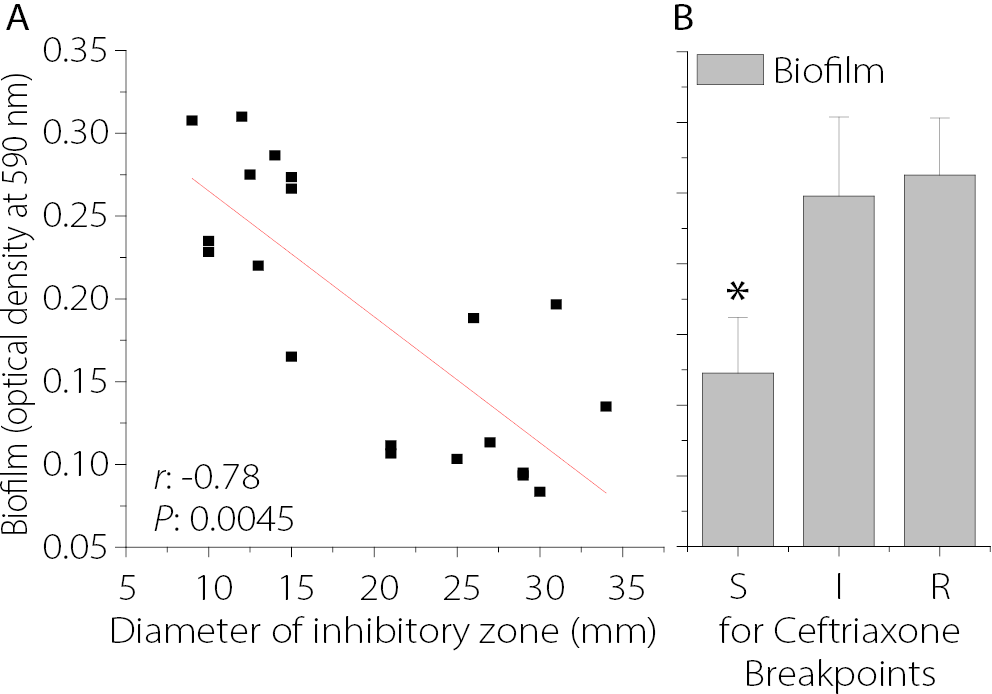

The susceptibility of 20 P. aeruginosa isolates to CRO was assessed using the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method. As shown in Figure 2, the smallest inhibition zone was observed for isolate Pa11 (9 ±0.6 mm), followed by Pa13 (10 ±1.01 mm) and Pa17 (10 ±0.9 mm). In contrast, the largest inhibition zone for CRO was observed in isolate Pa10 (34 ±4.2 mm), as shown in Figure 2A. The levels of biofilm formation for the 20 P. aeruginosa isolates are presented in Figure 2B. Among them, Pa19 (0.31 ±0.011) and Pa11 (0.307 ±0.02) exhibited the highest levels of biofilm production, whereas Pa1 showed the lowest biofilm formation (0.085 ±0.02). Among the 20 P. aeruginosa isolates, 7 produced strong biofilms, 10 exhibited moderate biofilm formation, and 3 were classified as weak biofilm producers. Isolate Pa11, which demonstrated the highest level of biofilm production and resistance to CRO, was selected for further experiments. In the present study, the MIC of CRO against Pa11 was determined to be 256 µg/mL. Figure 3A illustrates the relationship between biofilm formation and the diameter of the inhibition zone of CRO for 20 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. A significant negative correlation was observed between biofilm-forming ability and susceptibility to CRO, as indicated by the diameter of the inhibition zones (r = –0.78, p < 0.005).

It was observed that P. aeruginosa isolates classified as sensitive to CRO produced significantly less biofilm (p < 0.05) compared to isolates exhibiting intermediate or resistant profiles. However, no significant difference in biofilm formation was found between the CRO-resistant and intermediate groups (Figure 3B).

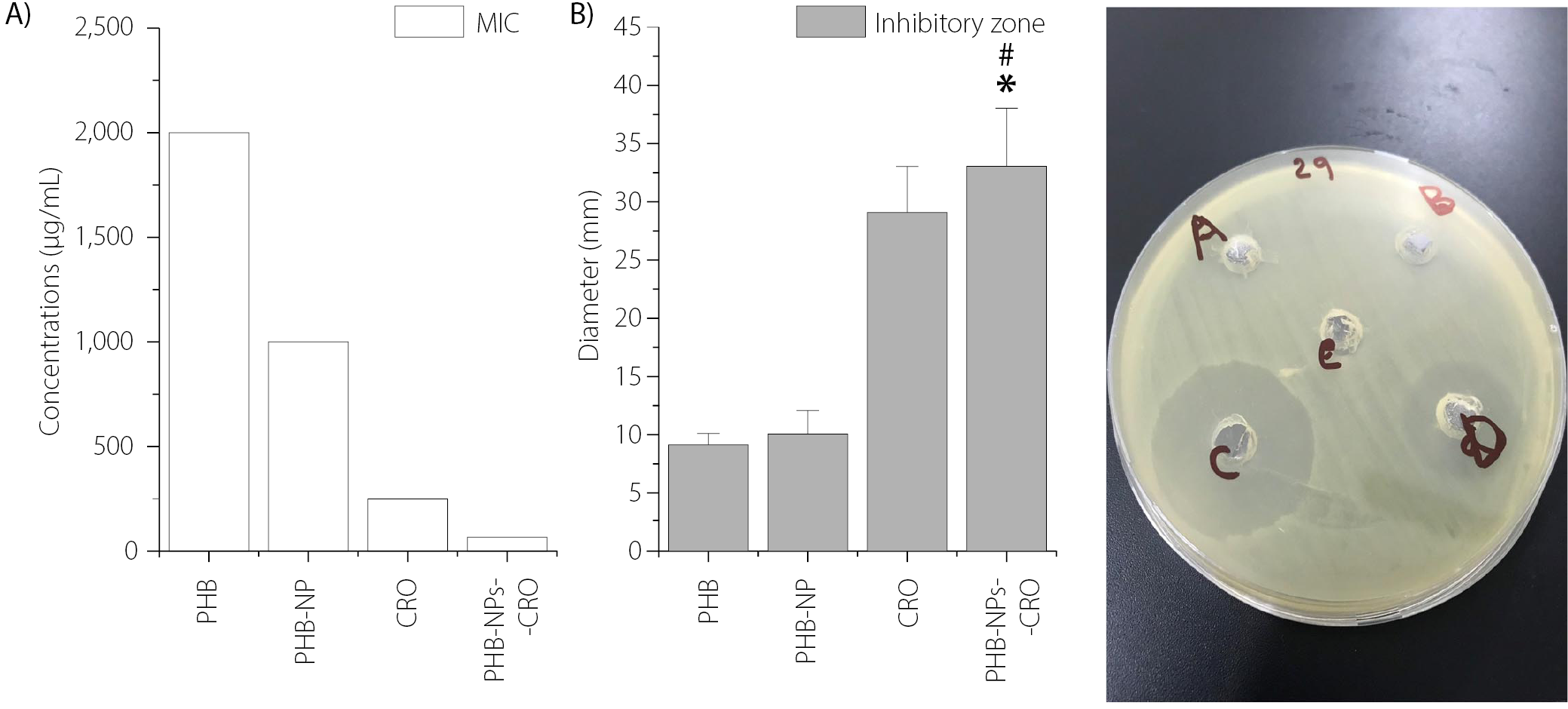

Susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to PHB-NPs and ceftriaxone

In the current study, P. aeruginosa isolate Pa11, which exhibited resistance to CRO and produced a high level of biofilm, was selected for further experiments. The microdilution method was used to determine the MICs of PHB, PHB-NPs, CRO, and the PHB-NP-CRO combination against Pa11. The highest MIC was recorded for PHB (2,000 µg/mL), followed by PHB-NPs (1,000 µg/mL). A notable reduction in MIC was observed for CRO alone (250 µg/mL), while the lowest MIC was achieved with the PHB-NP-CRO formulation (62.5 µg/mL), as shown in Figure 4A.

Figure 4B presents the diameters of the inhibition zones produced by various treatments against P. aeruginosa isolate Pa11. The largest inhibition zone was observed around the well containing PHB-NP-CRO (100 μL), measuring 33.1 ±5.13 mm, followed by CRO alone (29.2 ±4.11 mm). In contrast, the smallest inhibition zones were recorded for PHB (9.2 ±1.3 mm) and PHB-NPs (9.8 ±1.9 mm). Figure 4C displays the visual representation of antibacterial susceptibility. Prominent inhibition zones were observed around the wells containing CRO and the PHB-NP-CRO formulation, indicating strong antibacterial activity. In contrast, smaller inhibition zones were noted around the wells filled with PHB and PHB-NPs. The central well, filled with DMSO, served as the negative control. These results confirm that PHB-NP-CRO exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect against P. aeruginosa, followed by CRO.

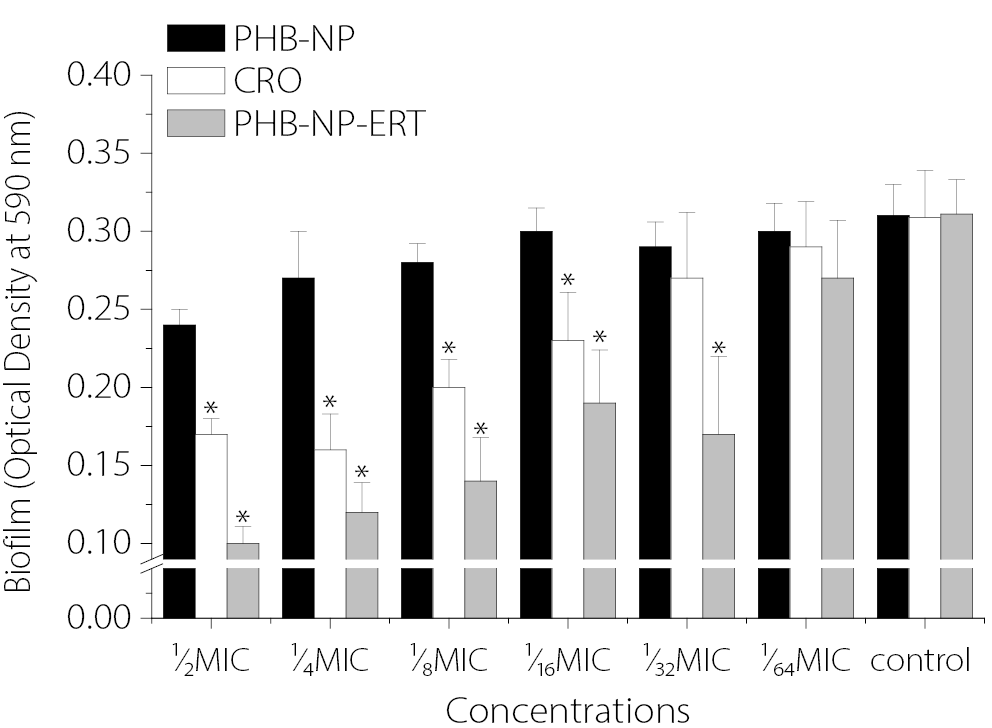

Effect of sub-MICs on biofilm formation

Figure 5 illustrates the effects of sub-MICs of PHB-NPs, CRO and the PHB-NP-CRO combination on biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa isolate Pa11. The results indicate that sub-MICs of PHB-NPs alone did not significantly inhibit biofilm formation. Sub-inhibitory concentrations (½ MIC, ¼ MIC, ⅛ MIC, and 1⁄16 MIC) of CRO significantly reduced biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa Pa11 compared to the control group pretreated with PBS (p < 0.05). Similarly, PHB-NP-CRO sub-MICs (½ MIC, ¼ MIC, ⅛ MIC, 1⁄₁₆ MIC, and ¹⁄₃₂ MIC) also resulted in a significant reduction in biofilm formation compared to the PBS-treated control (p < 0.05). The greatest inhibition of biofilm formation was observed with sub-MICs of PHB-NP-CRO, followed by sub-MICs of CRO alone.

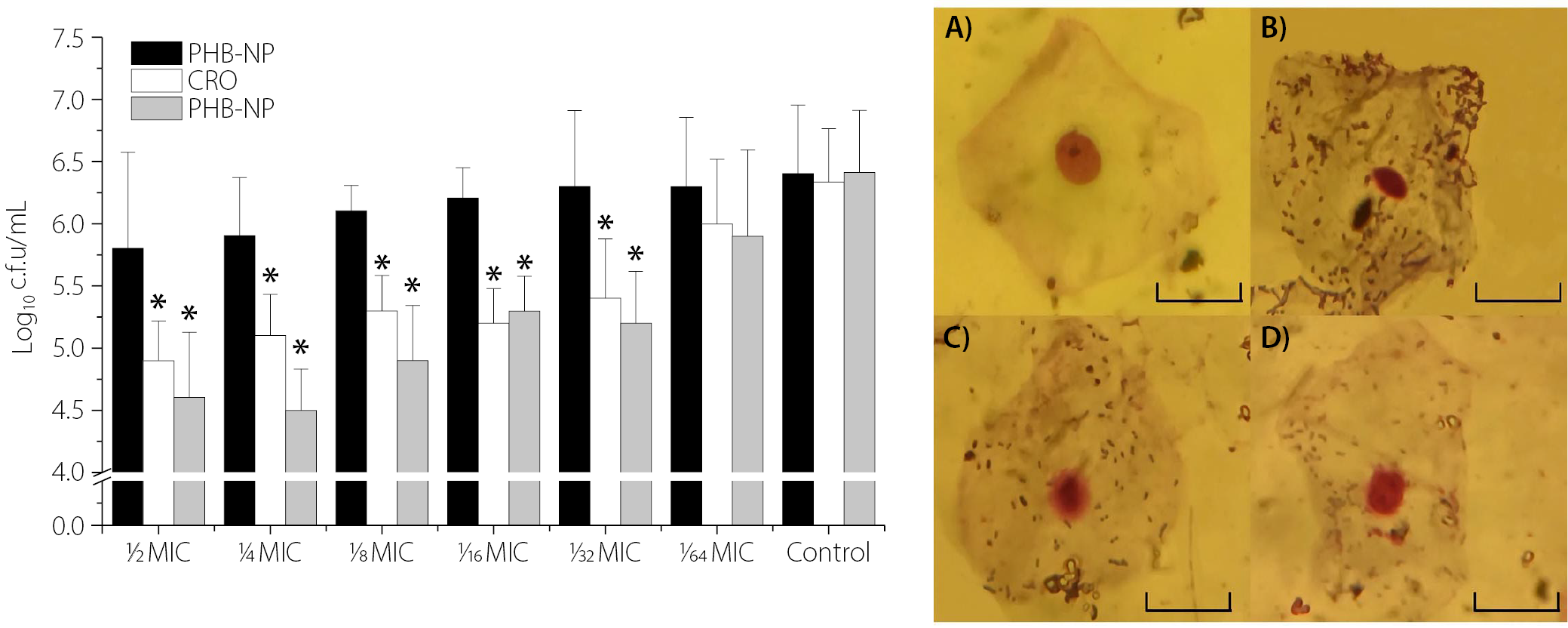

Effect of sub-MICs on adhesion to human OMECs

Figure 6 illustrates the impact of pre-treatment with different sub-MICs of PHB-NPs, CRO and the PHB-NP-CRO combination on the adhesion of P. aeruginosa Pa11 to human OMECs. No significant difference was observed in the number of adhered Pa11 cells pretreated with PHB-NPs compared to the control group (Pa11 pretreated with PBS). A significant reduction (p < 0.05) in the number of adhered P. aeruginosa Pa11 cells was observed following pre-treatment with sub-MICs of CRO (½ MIC, ¼ MIC, ⅛ MIC, ¹⁄₁₆ MIC, and ¹⁄₃₂ MIC). However, no significant difference was found in adhesion when Pa11 was pre-treated with 1⁄64 MIC of CRO (p > 0.05). A similar pattern was observed for Pa11 cells pre-treated with sub-MICs of PHB-NP-CRO. Figure 6A shows human OMECs with normal flat morphology and centrally located nuclei. In contrast, Figure 6B reveals a high density of P. aeruginosa Pa11 adhered to OMECs following pre-treatment with PBS (control). A noticeable reduction in bacterial adhesion was observed when OMECs were exposed to Pa11 pre-treated with CRO at ⅛ MIC (Figure 6C) and PHB-NP-CRO at ⅛ MIC (Figure 6D). The present study demonstrated that the PHB-NP-CRO formulation produced the most substantial reduction in bacterial adhesion to the epithelial surface, followed by CRO alone.

Discussion

Infection with P. aeruginosa strains resistant to broad-spectrum antibiotics presents a serious challenge for clinicians.17 This is largely due to the bacterium’s intrinsic resistance mechanisms and its ability to form biofilms.1 The biofilm matrix provides protection to bacterial cells, enabling them to evade the effects of antibiotics and the host immune response.18 The resistance of P. aeruginosa to antibiotics – particularly to CRO, a third-generation cephalosporin – has increased markedly in recent years.19 As a result, the development of safe and effective strategies to limit bacterial resistance has become essential. One promising approach involves the use of biocompatible materials to inhibit biofilm formation, a key factor in the persistence and resistance of bacterial infections.18

In the present study, PHB-NPs were synthesized, and their synergistic effect with CRO in reducing P. aeruginosa resistance and biofilm formation was evaluated. The findings demonstrated that PHB-NPs enhanced the antibacterial efficacy of CRO. Notably, sub-MICs of the PHB-NP-CRO combination significantly reduced biofilm formation and impaired P. aeruginosa adhesion to epithelial cells in vitro. Furthermore, the combination of CRO and PHB-NPs not only exhibited potent antibacterial activity, but also reduced bacterial virulence by inhibiting biofilm formation and adhesion to biotic surfaces, such as human OMECs. Since biofilm formation and adhesion are key virulence factors of P. aeruginosa, their suppression significantly enhances the therapeutic potential of this combination strategy.20

Previous studies on PHB-NP synthesis reported findings consistent with the current study regarding particle size. For instance, Deepak et al. reported PHB-NP diameters ranging from 100 nm to 125 nm,21 while Pachiyappan et al. obtained particles with a broader size range of 50 nm to 300 nm.7 In contrast, the PHB-NPs synthesized in the present study exhibited significantly smaller diameters, ranging from 15 nm to 34 nm, suggesting an improvement in the efficiency of the preparation method employed. The primary applications of PHB-NPs include drug delivery,22 as well as antibacterial activity. Kiran et al. demonstrated the antibacterial efficacy of PHB-NPs against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms.23 In addition, Rodriguez-Contreras reported the anticancer potential of PHB.24 More recently, Hamdy et al. highlighted the utility of PHB in wound healing, tissue regeneration, and bone and tissue engineering.25 Polyhydroxybutyrate is a safe, biodegradable polymer with various biomedical applications, largely attributed to its antibacterial properties.23 The biomedical potential of PHB-NPs lies in their ability to facilitate targeted antibiotic delivery. The observed synergistic enhancement of CRO’s antibacterial activity by PHB-NPs may be attributed to improved diffusion of CRO across the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa. Furthermore, the transformation of PHB into nanoparticle form appears to enhance its antibacterial effect when combined with CRO. PHB-NPs may interfere with quorum sensing and inhibit polysaccharide production, thereby disrupting biofilm formation and increasing bacterial susceptibility to CRO. In addition, CRO itself is known to inhibit quorum sensing mechanisms.26 The nanoparticulate nature of PHB-NPs may also facilitate interactions with bacterial membranes, leading to increased membrane permeability and enhanced intracellular accumulation of CRO.26 The findings of the present study highlight the promising potential of PHB-NPs in antimicrobial applications. They were shown to enhance the efficacy of CRO, enabling a reduction in the required antibiotic dosage and potentially minimizing associated side effects. This approach may offer a valuable strategy for combating broad-spectrum antibiotic-resistant P. aeruginosa. The observed ability of the PHB-NP-CRO combination to inhibit biofilm formation further suggests its potential use in treating biofilm-associated infections, including respiratory tract infections,27,28 urinary tract infections15 and medical device-related infections (e.g., catheters and prosthetic implants).29 Therefore, the present study supports the use of PHB-NP-based systems as a novel approach to restoring the therapeutic efficacy of existing antibiotics against resistant bacterial strains. Based on the findings of the present study, we recommend conducting in vivo studies to further validate the observed effects. In vivo investigations are essential to evaluate the safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetic profile of the PHB-NP-CRO combination in a physiological environment. Additionally, the use of animal models and future clinical studies will be crucial in assessing the therapeutic potential, bioavailability and potential immunological responses associated with PHB-NP-CRO administration. Furthermore, evaluating the antimicrobial efficacy of PHB-NP-CRO against a broader spectrum of bacterial species, including Gram-positive and multidrug-resistant pathogens, will provide valuable insights into its potential application for the treatment of diverse infections.

Conclusions

Resistance of P. aeruginosa to CRO is a major public health concern. The use of safe materials that enhance the efficacy of antibiotics represents a promising therapeutic strategy. In the present study, PHB-NPs were synthesized; however, they exhibited limited antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa when used alone. In contrast, the PHB-NP-CRO demonstrated a significantly enhanced antibacterial effect compared to either agent alone. The increased effectiveness of the PHB-NP-CRO formulation may be attributed to several factors, one of which, as shown in this study, is its ability to reduce biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.