Abstract

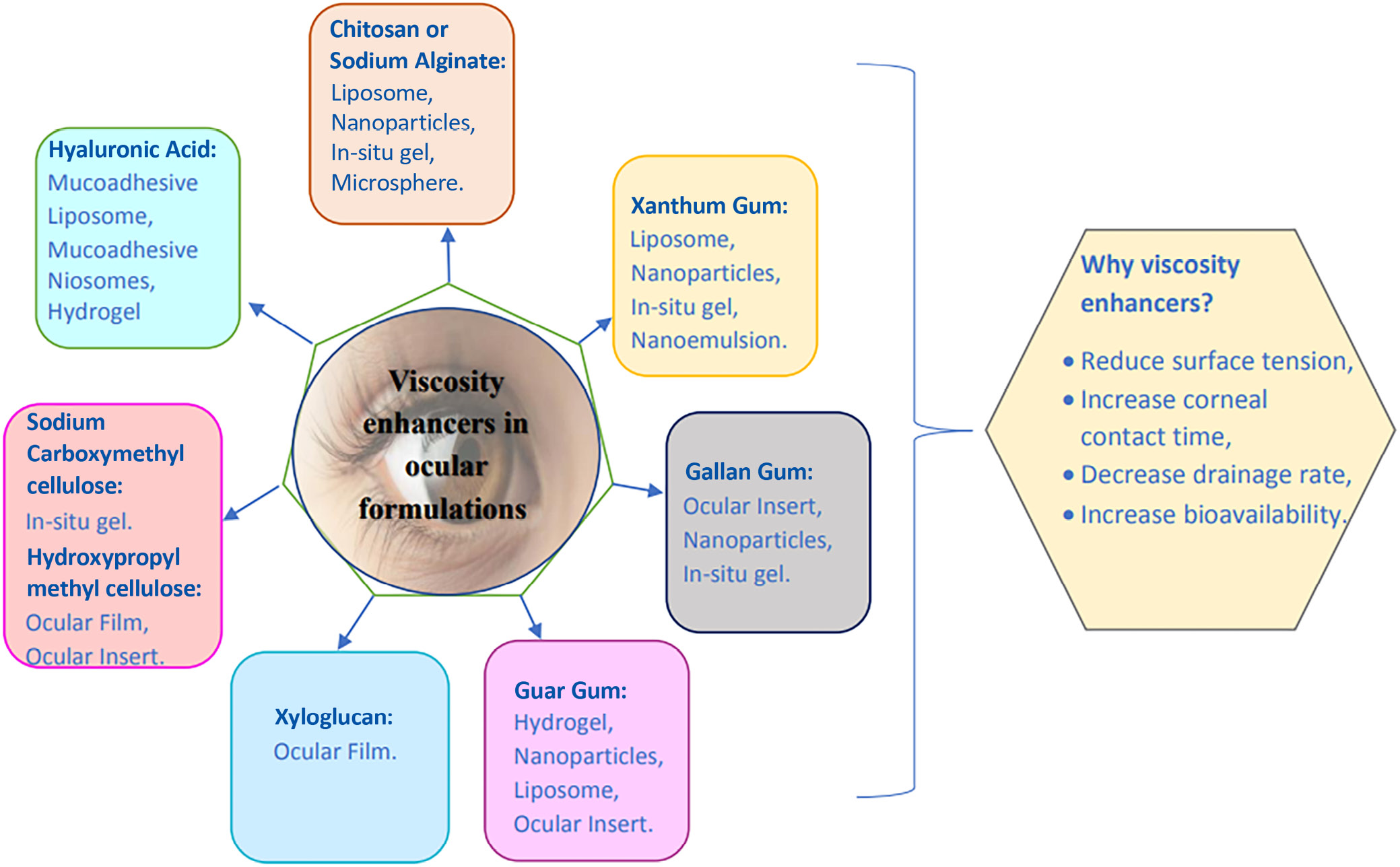

The eye is the most accessible site for topical drug delivery. Drug’s ocular bioavailability is quite low when administered topically as eye drops. Viscosity enhancers are used to increase ocular bioavailability by extending the precorneal residence time of the drug at the ocular site. Cellulose, polyalcohol and polyacrylic acid are examples of hydrophilic viscosity enhancers. The addition of viscosity modifiers increases the amount of time the drug is in contact with the ocular surface. Several polysaccharides have been studied as excipients and viscosity boosters for ocular formulations, including cellulose derivatives such as chitosan (CS), xyloglucan and arabinogalactan (methylcellulose, hydroxyethylcellulose, hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC), and sodium carboxymethylcellulose). Viscosity-increasing substances reduce the surface tension, extend the corneal contact time, slow the drainage, and improve the bioavailability. Chitosan is a viscosity enhancer that was originally thought to open tight junction barrier cells in the epithelium. Chitosan thickens the medication solution and allows it to penetrate deeper. Alginate is an anionic polymer with carboxyl end groups that has the highest mucoadhesive strength and is used to improve penetration. Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), a polysaccharide with a high molecular weight, is one of the most common viscous polymers used in artificial tears to achieve their longer ocular surface residence period. Hyaluronic acid (HA) is biocompatible and biodegradable in nature, and it is available in ocular sustained-release dose forms. A polymer known as xanthan gum is used to increase viscosity. At 0.2% concentration, carbomer forms a highly viscous gel.

Key words: polysaccharides, mucoadhesive strength, retinal bioavailability, viscosity enhancer

Introduction

Topical administration to the eye is the method most frequently used for the treatment of different eye conditions. Ocular medications are only partially absorbed due to the eye’s strong defensive mechanisms. Some of the processes that clear debris from the surface of the eye include drainage, baseline lachrymation, reflex lachrymation, and blinking. Drug absorption is further aided by the cornea’s physiology, composition and barrier performance. Toxic side effects or prolonged contact with very concentrated liquids may cause eye damage. The use of a mucoadhesive, which has been helpful in mucosa and oral applications, was another technique for refining the ocular dose form. One investigation focused on the interaction of mucins with natural and synthetic polymers. Interactions with the ocular structures or mucus layer required longer precorneal preparation. Several mucoadhesive polymers were found to enhance drug absorption, accelerate wound healing and safeguard epithelial cells.1

The eye is an extensive organ with unique structure and physiology that obstructs the entry of medicines into the intended ocular locations. Researchers have been interested in effective topical administration for many years. Their goal has been to increase medication residence time and achieve proper ocular penetration.2 Precorneal, corneal and blood–corneal barriers, among others, prevent the effective transport of drugs to the ocular regions. Topical, intravitreal, intraocular, juxtascleral, subconjunctival, intracameral, and retrobulbar delivery methods are available for ocular administration. More than 95% of commercially available ophthalmic formulations are in liquid state.3

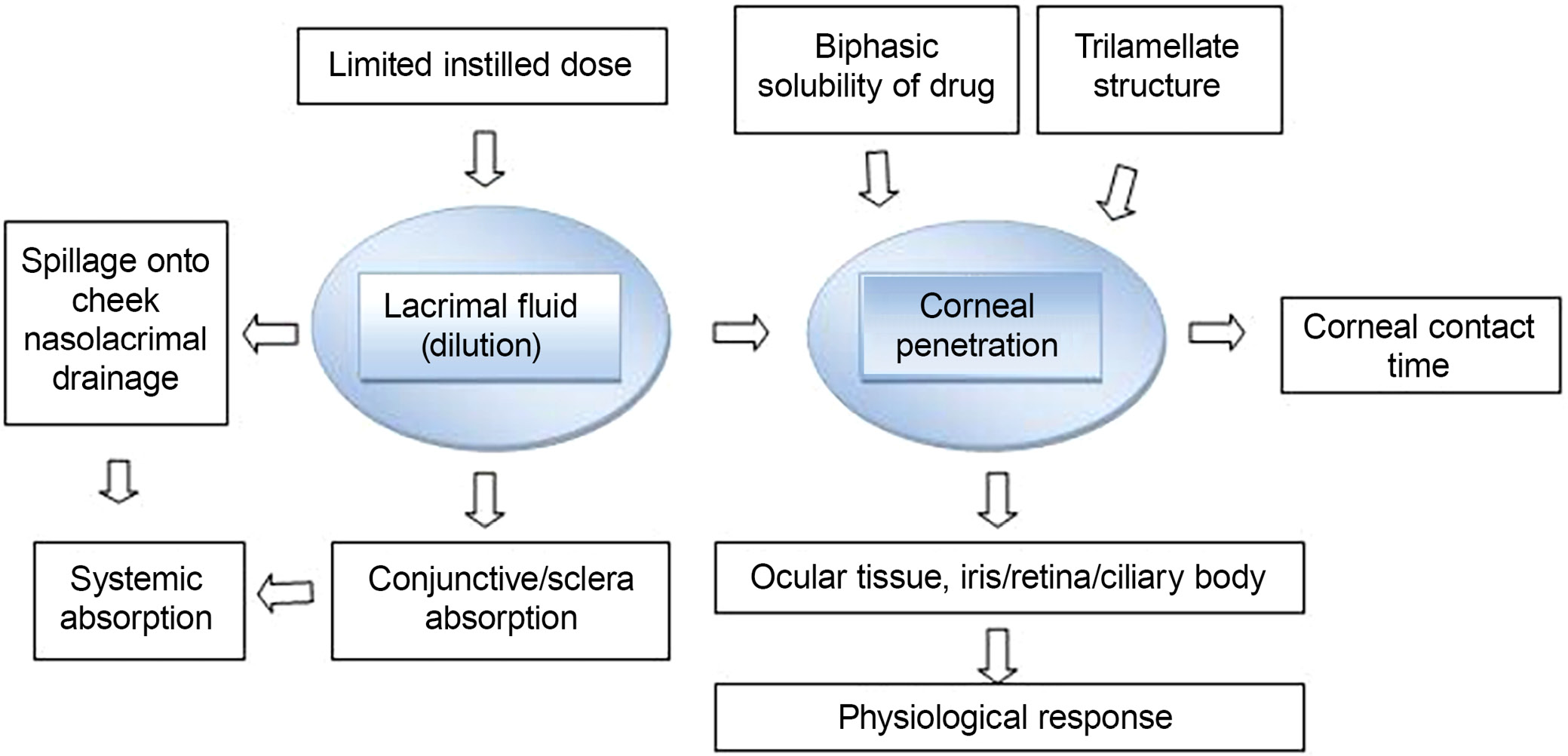

Although many medications are effective in treating the majority of ocular diseases, there are numerous ocular barriers, including tear film, corneal, conjunctival, and blood–ocular barriers, which limit the therapeutic efficiency of these medications. Both tear production and blinking deplete conventional eye drops. The bioavailability of these drugs is thereby reduced by 90%. As per ocular delivery concern, the first rate-limiting step is cornea. Therefore, to achieve higher bioavailability of therapeutic agent at any dose, the minimal penetration is achieved through the cornea. The cornea is made up of epithelium, stroma and endothelium. Only tiny, lipophilic medications can pass through epithelium, but hydrophilic medications can flow through the stroma. The endothelium protects the corneal transparency and allows for the targeted entrance of hydrophilic medicines and macromolecules into the aqueous humour.4, 5 Comparatively speaking, the conjunctiva has less of an impact on drug absorption than the cornea, yet specific macromolecular nanomedicines, peptides and oligonucleotides easily reach the deep layers of the eye through these tissues. Xenobiotic substances cannot enter the bloodstream because of the blood–ocular barriers. The blood–aqueous barrier (BAB) is found in the anterior portion of the eye, and the blood–retinal barrier (BRB) is found in the posterior segment.

The goal of this review is to discuss different viscosity-enhancing agents that are used for improving ocular bioavailability. To achieve and maintain an optimal medication concentration with the least amount of the active therapeutic component, successful ocular absorption requires both effective precorneal residence time and appropriate corneal penetration.

In accordance with several literature reviews, this study focused on a few additional properties of viscosity-enhancing agents that enhance residence duration and improve corneal permeability in the ocular region and are useful for formulation issues.

Current review intends to summarize the existing conventional formulations for ocular delivery and their advancements, followed by polymers that are used in the ocular drug delivery system based on the formulation developments.

Gap between the ocular regions

This review aimed to fill in the gaps left by earlier studies that have been published on the viscosity-enhancing agents used in the administration of ocular medication. Various anatomical features of the eye, various ocular diseases, barriers to ocular delivery, various methods of ocular administration, classification of dosage forms, numerous nanostructured platforms, characterization approaches, strategies to improve ocular delivery, and future technologies were just some of the topics covered in a thorough description of ocular drug delivery from various directions.

Anatomy and physiology

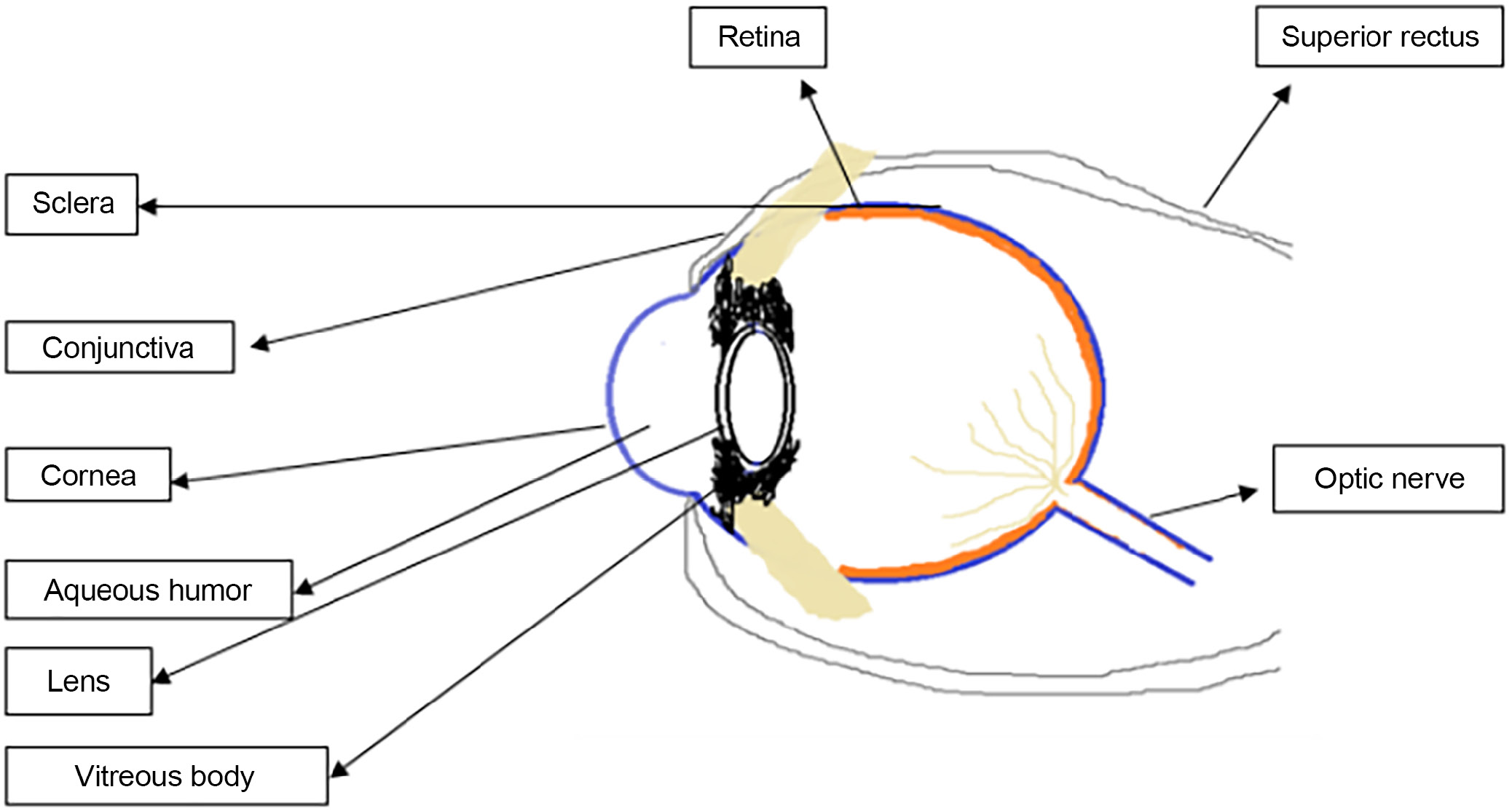

The eyeball’s 3 layers are an inner coat, a uveal coat, and the sclera and the cornea on the outside (retina). The sclera is made up of sphere-like structures, and the cornea and sclera are both made up of fibers. The flexible front section of the eyelids shields the eye’s outer surface. The sclera fissure can open and close based on how rapidly the fragile skin of the eyelids folds over the eyeball.

One can close their eyes either intentionally or involuntarily (via reflex and spontaneous blinking). Sclera fissure provides an optically smooth surface to the cornea by distributing tear fluid throughout the eye. The translucent cornea of the eye extends forward and has an approximately spherical shape. The eyelids, tears, blinking, and lashes are considered ocular defense mechanisms. Blinking often occurs to keep the ocular surface moist using tears secreted by the lachrymal gland and clean the mucus. The blink reflex closes the eyelids to protect them from damage, and the eyelashes trap anything that might fly in while they do so. Tears, because of their antibacterial properties, soothe irritations and protect the body from infections. The defensive mechanisms of the eyelids and cornea ensure that any substance injected into the eye is quickly removed through the lachrymal system. It is not a modest volume unless it is chemo- and physio-compatible with surface tissues.6

Structure of the eye

Along with the extrinsic eye muscles, the lachrymal system (which produces tears) develops. The components of the lachrymal apparatus produce and discharge lachrymal fluid, sometimes known as tears.

The vitreous chamber, the largest of the 3 chambers, is filled with a translucent, jelly-like fluid called vitreous humor. As a result, the health of the eyeball, lens, retina, intraocular pressure, and light refraction within the eye are all protected. Layers of the eye are made up of vascular, fibrous and neuronal tissues. The cornea and sclera are the 2 fibrous outermost layers of the eye. The choroid, ciliary body and iris are examples of intermediate vascular layer structures (Figure 1).

Fibrous layers of the eye

The cornea

The cornea, a fibrous layer that is external and transparent, makes up 1/6 of the eyeball. The endothelium, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, Bowman’s membrane, and epithelial membrane are the 5 structural layers of the cornea. There are 5 sublayers and a 50–100-μm thick outer epithelium of the human cornea. The epithelium’s lipophilic character accounts for around 90% of the barrier to hydrophilic drug entry, whereas hydrophobic drug entry accounts for just 10% of the barrier. The Bowman’s membrane is considerably thinner than the epithelium, with a thickness range of 8–14 μm. This layer serves as a barrier to prevent medications from entering the cornea, despite the fact that it cannot be regenerated if it is damaged. Mucopolysaccharides, collagen and other proteins make up the 20% of the stroma’s dry weight that is not made up primarily of water. Therefore, it is believed that the stroma is responsible for preventing the absorption of lipophilic medicines across the cornea. The membrane that follows is known as the Descemet’s membrane. Studies revealed that the 6-μm layer, a thin regeneration membrane, has little impact on how well ocular medications are absorbed. The posterior corneal surface is enveloped by a cell layer resembling the endothelium. These cells, linked by gap junctions, exhibit a permeability 200 times greater than that of the epithelial layer. This structure facilitates active fluid drainage and efficient fluid removal.

The sclera

The sclera, or “white of the eye,” covers 5/6 of the eyeball. The stiff, collagenous connective tissue and elastic fibers give it a white, opaque look. It develops the eyeball, shields the internal organs and tissues of the eye, and protects the eye. According to research, the sclera has a strong molecular radius dependence and is highly permeable to hydrophilic medicines. Water-soluble substances with a reduced molecular weight can thus more efficiently penetrate the pores and cytosol of the sclera.

The conjunctiva

This double or triple epithelial layer is made up of 3 major cell types: neurogenic epithelium, relevant epithelium integration and anterior epithelium. Despite their near proximity, these cells are more permeable to hydrophilic chemicals than the cornea. Greater permeability is caused by larger paracellular epithelial holes and an increase in epithelial pores.

The neural layer of the eye

The retina is located in the ocular layer, which is the eyeball’s innermost layer. Layers of pigmented cuboidal cells and light-sensitive neurons line the inside and outside of the retina, respectively. This layer of the brain also comprises 6–7-μm photoreceptor cone cells and 120-μm photoreceptor rod cells. The macula and fovea of the retina are both illuminated. The fovea of the retina has more photoreceptors than any other portion of the retina, thus when light is concentrated there, visual acuity is at its peak. The optical disc has a “blind spot” because it lacks photoreceptor cells. The retinal artery and vein enter and leave here.

The vascular layer of the eye

Melanin pigments, which are mostly located in the vascular layer’s cells, are responsible for the dark color of the layer. The ophthalmic artery branches and the tiny ciliary arteries that wrap around the optic nerve vascularize the eye. The vascular layer of the eye, in addition to the choroid, ciliary body and iris, includes the majority of the blood vessels. The choroid, the circulatory layer’s deepest layer, lines the sclera’s inner surface. This layer creates the blood–ocular barrier, which strictly regulates the passage of chemicals from the blood into the eye.7

Ophthalmic disorders

Conjunctivitis

Bacteria, viruses, allergens like pollen and dust, smoking, and pollution can all cause ocular inflammation. It distinguishes itself from other conjunctivitis by its capacity to secrete and infiltrate cells. Staphylococcus aureus is the most prevalent cause of bacterial conjunctivitis and blepharon conjunctivitis. Furthermore, Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumonia can cause conjunctivitis.

Glaucoma

Inadequate aqueous humor outflow causes pressure to build up in the front and posterior chambers of the choroid layers. Glaucoma can cause permanent eyesight loss as well as severe and irreversible visual loss, if left untreated.

Keratitis

Keratitis is an eye infection caused by viruses, bacteria or fungi. Bacterial corneal ulcers are more frequently caused by viral infections. The most common causes of corneal ulcers are S. aureus, Pseudomonas pyocyanea, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis.

Dry eye syndrome

The area around the eyes has extremely dry skin. The characteristic of dry eye syndrome, sometimes referred to as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, is inflammation of the lachrymal glands and ocular surface.

Iritis

The usual acute side effects include inflammation and eye irritation. Aside from that, chalazas, ophthalmic rosacea variations, and blepharitis (lid edge inflammation) are also medical conditions (meibomian cysts of the eye lid).8

Ocular drug delivery system

Medication of specific impact above surface or interior of the eye is regularly delivered to the ocular system. Topically applied medications, such as eye drops, have a limited bioavailability. The nasolachrymal system is used to inject a dose into the nasopharynx in order to improve the duration of therapeutic activity and ocular bioavailability. Despite improving corneal contact length to varying degrees, these devices have not been widely adopted because of eye pain (ointments), poor patient compliance (inserts) and lid sticking (gels). Their place has been replaced by ointments, gels and polymeric implants. Because of eye irritation (ointments), poor patient compliance (inserts) and lid sticking, all of these technologies extend the duration of corneal contact to varying degrees (Figure 2). Recently, it was shown that pH- and temperature-induced in situ forming systems, such as carbopol and cellulose acetate phthalate, can keep ocular drugs administered. These in situ gel production strategies may improve ocular bioavailability by increasing a drug’s precorneal residence duration. Drugs with low bioavailability due to poor permeability and solubility can be made more accessible by utilizing a variety of techniques. Increased drug absorption and longer ocular residence times are being worked on in order to increase topical bioavailability and therapeutic responsiveness of ophthalmic medicines. The formulation viscosity was increased to improve ocular bioavailability and the drug’s precorneal residence duration at the ocular site. Hydrophilic viscosity enhancers such as cellulose, polyalcohol and polyacrylic acid are examples. Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose is the most important mucoadhesive polymer with strong adherence. The addition of carbomer increases the viscosity of liquid and semisolid solutions. Because it binds form and has mucoadhesive properties, hydrogel aids in drug delivery system maintenance. Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a naturally occurring substance that is both biocompatible and biodegradable. It is available in dose formulations that provide a sustained release for the eyes. The polysaccharide xanthan gum can be used to enhance viscosity. A viscosity vehicle increases contact time and improves ocular absorption. A viscosity enhancer can be added to an ophthalmic solution vehicle to lower the size of the injected drop while increasing the viscosity of the solution in order to improve ocular absorption, increase the viscosity of the solution and add a viscosity enhancer to an ophthalmic solution vehicle. Poorly absorbed medications can be more successfully absorbed by improving ocular absorption. Using viscosity modifiers to extend the time the medicine is in contact with the ocular surface, for example, can assist increase drug bioavailability. Other techniques include particle retention at the site of administration following ocular delivery, polymer breakdown, diffusion-based drug release, chemical reaction processes, and drug release. Particulate medicine delivery techniques utilize the nanoparticles and microspheres. Chitosan (CS) is a bioadhesive carrier that is suitable for ocular formulation owing to its intrinsic biological properties, which include biodegradability, nontoxicity and biocompatibility.9 Salicylic acid reacts ionically with its opposing charges because of its positive charge and neutral pH. Carrageenan and xanthan are both bioadhesive polysaccharides. When surface tension is reduced, longer corneal contact durations result in slower drainage and greater absorption. This is the fundamental purpose of viscosity-increasing compounds.9, 10 (Figure 3.)

Viscosity enhancers used in ocular drug delivery system

Viscosity modifiers are chemicals that are used to alter the thickness or texture of medicinal substances. Thickeners, texturizers, gelation agents, and stiffening agents are examples of viscosity modifiers. Table 1 presents viscosity profiles of selected viscosity-enhancing agents.

Chitosan

Chitosan is a positively charged mucopolysaccharide found in the shells of insects and crustaceans that is produced through chitin deacetylation. It contains both N-acetylglucosamine and glucosamine. Chitosan’s acetylation level has a substantial impact on its solubility; the higher the acetylation level, the more CS is affected. The amine group in CS has a pKa of about 6.5 and is soluble at acidic pHs but insoluble at neutral pHs. Chitosan, a viscosity enhancer, was considered to open epithelial tight junction barrier cells and intracellular cells. Chitosan increases cell permeability without impairing viability. Because of this increased permeability, more drugs are transported across the cornea. It is also naturally biodegradable and has mucoadhesive properties. The majority of organic acidic solutions, such as citric, formic, acetic, and tartaric acids, are dissolved by CS. Phosphoric and sulfuric acids are not dissolved with CS. It is highly soluble in organic acids due to its ability to generate protonated amines and exhibit polycationic properties at pH values lower than 6. Chitosan concentration can be increased by cutting it into quarters to produce trimethyl CS. It is soluble in both neutral and basic pH ranges.11

At pH values above approx. 6.5, CS amines become reactive and deprotonated, encouraging polymer connections and the formation of fibers and networks (i.e., film and gel). Chitosan’s structure has been altered to improve properties such as mucoadhesion and penetration. Chitosan penetration capability is improved when given a thiol group by creating disulfide linkages with the cysteine residues on mucin. Several eye disorders could possibly be addressed by using these effects. Chitosan improves faster corneal repair by hastening kerocyte migration, which accelerates wound healing and collagen synthesis. According to Gurtler et al., the optimal CS dose for topical ophthalmology is 1.5% when compared with CS that has a low molecular weight range of 500–800 kDa.

Chitosan-based formulations

Chitosan nanoparticle

The use of CS nanoparticles enhanced drug bioavailability to the ocular mucosa. Tighter contact benefits such systems, and distribution to the outside ocular tissues should be increased without jeopardizing the inner ocular structures.12, 13 Chitosan nanoparticles were researched to evaluate if they could be used to deliver ocular drugs in vivo; their toxicity in conjunctival cell cultures was also examined. The fluorescent nanoparticles were generated using the ionotropic gelation process.14, 15 To test the particle stability in the presence of lysozyme, the size, viscosity of the mucin dispersion and particle interaction with mucin were all examined. The in vivo interactions of CS-fluorescent (FL) (CS-FL) nanoparticles with rabbit cornea and conjunctiva were investigated using spectrofluorimetry and confocal imaging. Chitosan nanoparticles are promising medication delivery platforms for the eye.16, 17

Chitosan microspheres

Microspheres enable precise and controlled drug administration. The incorporation of penetration enhancers, such as CS, into microspheres has the advantages, such as the bioavailability and improved retention time due to much closer contact with the mucus layer, and accurate targeting of medications to the ocular region.18 The use of CS microspheres enables prolonged in-vivo ocular medication release. Chitosan is useful for drug release control due to its mucoadhesive characteristics. Overall, each particle system provides a feasible technique for improving drug bioavailability in the eye.19

Chitosan of in situ gelling system

In situ gel combines the advantages of liquid and gel. It is precise and easy to operate. Before administration, the medicine was in the solution form; during administration, it was in the gel form. As a result, less medication is lost and the drug remains in the precornea of the eye for longer. Also, the medicine is more bioavailable.20, 21 Temperature and pH fluctuations can activate in situ gelling processes. Chitosan, a polymer sensitive to pH changes, has the capability to enhance the viscosity of a substance. By combining CS in situ gel with polaxamer, the resulting gel’s mechanical strength surpasses that of either component on its own, making this combination especially advantageous for ocular delivery.22

Chitosan solutions

When administered topically, polycationic CS compounds that are soluble at the physiological pH of tear fluid enhance penetration. The precorneal residence was extended by tobramycin and CS solutions. The therapeutic solution’s viscosity and permeability have increased as a result.23

Chitosan liposomes

Liposomes, which are colloidal drug delivery techniques, have better ocular bioavailability than standard liquid formulations. Although they have some advantages, such as ease of administration, better bioavailability and no effect on vision, there are also some disadvantages. Drugs leak due to their rapid fusion or disintegration while being stored or administered.24 To address these issues, liposomes were coated with low-molecular-weight CS. Because of the CS coating, the liposomes have high penetration and a positive charge. Chitosan coating improves precorneal retention compared to liposomes without a coating. Chitosan coating increased transcorneal medication absorption through modulating CS influence on drug penetration.25

Sodium alginate

Due to its high degree of hydrophobicity, biocompatibility and low cost, alginate is a popular pharmaceutical delivery alternative. In situ gelling system that is based on polymers appears to be a better drug delivery strategy. Most mucoadhesive polymers are found in the form of sodium alginate, an anionic polymer containing a carboxyl end group. When alginate is slowly dissolved in water, it creates a gel. The solution has permeated high viscosity.26, 27

Sodium alginate-based formulations

Sodium alginate nanoparticle

Sodium alginate, an interesting polysaccharide, has found applications in diverse ocular delivery systems, both independently and in combination with other substances. Innovative nanoparticles have been created using sodium alginate encapsulation, facilitating gradual medication transport to the ocular mucosa.28 Because of its excellent biological properties, such as renewability and non-toxicity, sodium alginate was chosen as an ocular formulation carrier. Alginic acid formulations with a prolonged precorneal stay were sought after due to their mucoadhesive properties and the ability to gel in the eye.

Sodium alginate microsphere

The sodium alginate technique was devised to deliver gatifloxacin to the ocular mucosa over time. The combination of biocompatible and biodegradable properties protects the encapsulated chemical and prevents its release more effectively than alginate or CS alone. It is a promising technique of drug release because of its properties, such as mild gelation conditions, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and pH dependence.29

Sodium alginate in situ gelling system

The porosity of these hydrogels, the initial viscosity of the alginate solution, the ratios between guluronic acid and mannuronic acid, the concentration of the ionic cross-linker – all these factors play a crucial role. Calcium serves as the initial cross-linker in the alginate solution. Calcium cross-linked polymers can physically capture and stimulate the release of a variety of compounds, even at low polymer solution concentrations.30 This phase shift occurs in the in situ gel conjunctiva of the eye. In the literature, numerous physiologic circumstances have been employed to document the sol–gel transition of various gels. These include CS, carbopol, sodium alginate, poloxamers, Pluronic® (Shilpa ChemSpe, Mumbai India), Gelrite (Opal Biotech, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India), xanthan, and polymeric copolymers. Many synthetic and organic polymers have the potential to improve drug bioavailability by extending the time drugs stay in the body.31 Aside from safety, biocompatibility and biodegradability, an excellent polymer-fabricated delivery system should be able to load medications and have a longer residence length at target tissues.

Xanthan gum

Higher quantities of locust bean gum produce soft, elastic and thermally reversible gels. At 1% or higher concentrations, xanthan gum solutions virtually appear gel-like at repose, yet they pour readily and provide little mixing or pumping issues. These properties are present at 0.1–0.3% of normal use levels. Xanthan gum solutions can help colloidal systems stay stable over time due to their high viscosity at low shear rates.32

Because xanthan gum solutions are significantly more viscous than sodium alginate or carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) at low shear rates and roughly 15 times more viscous than guar gum at high shear rates, they are more effective at stabilizing suspensions. Because of chemical forces such as van der Waals interactions, xanthan gum has a double-stranded helix structure and a low ionic strength in an aqueous dispersion. To properly link with the co-synergist, the conformation of the xanthan gum molecule must be pushed over if it is in an ordered state at the time of mixing. The physicochemical features of xanthan gum, as well as variations in molecular conformation, have an effect on the substance’s capacity to attach to mucous membranes. Secondary bonds formed between double-stranded helices increase polymer concentration and elastic characteristics.33 Mucin must be present in substantial quantities for xanthan gum to interact. To keep the scattered granules from settling, the liquid must be constantly swirled after being added to the xanthan gum solution until it is completely dissolved. Xanthan gum is a carrier for a number of eye diseases, including proliferative uveitis and choroiditis. Proliferation of tumors causes uveitis.34 Retinopathy of prematurity, posterior segment trauma and retinal vascular pathology are all names used to characterize inflammatory retinal diseases. According to the in vivo trial with healthy volunteers, xanthan gum solutions of greater viscosity take longer to clear following injection. Therefore, xanthan gum outperforms poly(vinyl alcohol), hydroxyethylcellulose and hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC) as a viscosifying agent. But, particularly at later time points, the gelation process of gellan gum performs better than that of xanthan gum.35, 36

Xanthan gum-based formulation

Xanthan gum in situ gelling

Devices that gel upon ion activation offer 2 advantages: they prompt gel formation on the ocular surface and extend the duration of corneal contact with the surface. The recent investigation of this in situ gelling system indicates high cost alongside compatibility considerations.37

Xanthan gum nanoemulsion

Angiogenesis inhibitor-containing targeted vesicles were administered intraocularly and greatly reduced choroidal neovascularization when compared to a placebo injection. Nanoparticle medication has emerged as a feasible option for cutting-edge ocular ailment therapy as a result of recent improvements in ocular drug delivery system research that have provided new insights into drug composition. Nanoemulsion (NE)-based topical formulations have the potential to create new options for clinical translation in ocular therapy by designing NEs for effective loading and delivery of ocular drugs to achieve the desired therapeutic effects or to behave in a specific ocular state.38

Gellan gum

Nanoparticle drug delivery has become a promising approach for cutting-edge ocular sickness treatment as a result of recent advancements in ocular drug delivery system research that new insights into drug creation.

Gellan gum is a recognized polysaccharide derived from an aerobic Gram-negative bacterium that serves as an energy source. Its structure comprises glucuronic acid, rhamnose and glucose in a 2:1:1 ratio, resulting in a repeat unit of tetrasaccharide through their combination.39 Gelrite, a commercial product, completely de-esters the native polysaccharide after being exposed to alkali, whereas L-glycerate and acetate only partially esterify the polymer. Gellan gum contains the following molecules: O-acetyl, rhamnose, glucose, and glucuronic acid. Gellan gum is easily hydrated and dissolves in both hot and cold deionized water; however, when employed with cold distilled water, it generates viscous solutions. When soluble salts are present, gellan gum can be utilized to form a strong gel at low concentrations. At high temperatures, gellan polymers exist in an arrangement known as an unorganized random coil in aqueous solutions.40 When polymers are cooled until they gel, double helices form and assemble to form junction zones. Cations stabilize the double helices and junction zones, resulting in a 3D gel network. Gellan gum is classified into 3 groups based on its structural composition: those with a high polysaccharide content, those with a high protein content, and those with a high polysaccharide O-acetyl replacement content. Indomethacin is gelled in situ using gellan gum. When this approach is applied in a test tube to generate sustained drug release for 8 h, there is no harm to the eye tissues. A novel ophthalmic carrier called Gelrite® gellan gum hardens when it comes into touch with monovalent or divalent cations in the lachrymal fluid.41

Gelrite is a better transporter than xanthan gum due to its inclination to gel. Gelation is characterized by the creation of an orderly state of gellan chains.42

Gellan gum-based formulations

System for in situ gelling of gellan gum

In situ gelling is used as a delivery strategy in one of the most promising ocular dosage forms. Liquid instillation facilitates administration while simultaneously increasing safety and frequency. Industrial preparation and manufacture are also simplified when compared to solid and traditional semi-solid forms. The most significant advancement of these smart hydrogels is a solution-to-gel phase transition induced by physiologically relevant ocular surface stimuli such as temperature, pH or ionic strength. These 2 chemicals, hydroxyethylcellulose-based and gellan gum, are used in in situ gelling delivery methods. Many gellan gum-based formulations have been shown to have prolonged in vivo ocular surface residence durations and the propensity to promote ocular gelling.43, 44 Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) was used to enhance viscosity, mucoadhesion and release properties while decreasing polymer concentration. In comparison to other cellulosic polymers, HEC is well tolerated and possesses the appropriate viscosity and lubricating qualities. All formulations are free of the majority of dangerous eye drop preservatives, such as benzalkonium chloride. Market trends, patient and practitioner expectations and the increasing number of publications on the issue support the effectiveness of polymers like gellan gum (Table 2).

Gellan gum ocular inserts

There are few insert goods on the market due to the difficulties of self-insertion and the perception of a foreign body. Because the production of gels is an extreme form of raising viscosity through the use of viscosity enhancers, the dosage can be reduced to once daily. Droppable gel is made by using modern gel production techniques. They transform from liquid to viscoelastic gel in the ocular cul-de-sac. For effective causation, 3 ways have been devised: pH change, temperature change and ionic activation phase transition in the ocular surface. Eye drops, ointments and lotions are some of the most commonly used topical medications for ocular delivery.45, 46 Because just a small percentage of the medicine is therapeutically helpful, dosage must be done on a regular basis. Gellan gum ocular inserts irritate the eye and obstruct vision, among other problems.

Guar gum

Guar gum is utilized in the pharmaceutical industry as a solid dosage form binder and disintegrant to improve the cohesiveness of prescription powders, as well as a suspending, thickening and stabilizing agent in oral and topical therapies. Guar gum is a common controlled-release component in medications due to its fast hydration. It is composed of galactose and mannose carbohydrates.47 Guar gum is insoluble in the vast majority of organic solvents, but it dissolves efficiently in both cold and warm organic solvents.

Guar gum-based formulations

Guar gum nanoparticle

The lack of stability required for a dependable drug administration strategy is the main drawback in the production of nanosized carboxymethyl guar gum nanoparticles by nanoprecipitation and sonication. Sodium trimetaphosphate (STMP), a non-toxic cyclic triphosphate, is extensively used to cross-link hydrogels and microspheres for therapeutic uses.48, 49 However, the nanoparticles must be cross-linked to avoid dissolving at different pH levels, which would deplete some of the free functional groups.

Guar gum-based liposome

Liposomes are water-filled containers with a membrane or bilayer covering. As opposed to phospholipid-based liposomes, they feature a core-shell arrangement in drug delivery systems, allowing for a superior encapsulating technique for extended drug release. Hydrophilic medications can be encapsulated by watery phospholipid-based liposomes, whereas hydrophobic drugs can be contained inside the lipid membrane. As a result, the liposomal smart design allows for the inclusion of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic medications.50

Guar gum-based ocular insert

Guar gum is used to strengthen the cohesiveness of the medicinal powder, as a binder and disintegrant in solid dosage forms, and as a suspending, thickening and stabilizing agent in oral and topical therapies. To address the limitations of existing ophthalmic dose forms, ofloxacin and guar gum (a biodegradable polymer) are being developed as ocular inserts with zero order kinetics (eye drops and suspensions).51 By altering the guar gum content, the release of ofloxacin from inserts was examined (polymer matrix).

Xyloglucan

The sugars arabinose, xylose, glucose, and galactose are mixed in the ratios of 4:3.4:1.5:0.3 to create xyloglucan, a galactoxyloglucan with a molecular weight of 720–880 kDa. The cell walls of higher plants are made up of xyloglucans, a type of linear polysaccharide. The xyloglucan’s viscosity is affected by the number of glycosyl and non-glycosyl subunits, the backbone molecular weight and the molecular weight. Tamarindus indica L. plants produce tamarind seed unionic and neutral carbohydrate xyloglucan (TSX), a tamarind seed sticky polymer.52, 53 Tamarind seed polysaccharide (TSP) is a compound with mucoadhesive, bio-adhesive, viscosity-increasing, and mucomimetic properties. At the O–6 position, the 14-linked glucan backbone chain of TSX is significantly replaced by d-xylose. These xylose residues have been found in O-254 in some cases.

Despite the fact that xyloglucan’s hydrophilic and hydrophobic characteristics make it soluble in water, aggregated species are present in the solution because individual macromolecules do not fully hydrate. They can be found in extremely diluted liquids. Thus, structure and function are interwoven in xyloglucan aqueous solutions. The xyloglucan content and inherent viscosity have the biggest influence on the random coil overlap and entanglement of the polymer backbone, respectively. When the concentration of xyloglucan in aqueous solutions increases, the random-coil structure appears. Carboxymethylation was used to change the properties of 55 TSPs.55, 56 The biodegradation of TSP is slowed by carboxymethylation, which also renders TSP more soluble in cold water and stable around bacteria. Even with a longer interval between doses of the medication, polysaccharide still enables prolonged reduction of S. aureus in the cornea. Tamarind seed polysaccharide increased drug accumulation in the cornea and prolonged antibiotic precorneal residence duration, most likely by lowering drug washout after topical administration.57

Gel-forming ocular film based on xyloglucan

The material’s major properties include its high drug retention, mucoadhesivity, biocompatibility, high thermal stability, and lack of carcinogens.58 Solvent casting was utilized to create an ocular film containing xyloglucan, which was then evaluated. Xyloglucan may produce a film with outstanding properties. The characterization outcome, which emphasizes the substance’s specific physical and mechanical properties, provides a clear indicator of its filmmaking potential. According to the research, ciprofloxacin could be given to the eye in an effective and consistent manner utilizing xyloglucan ocular films.59

Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose

Carboxymethylcellulose, a high-molecular-weight polysaccharide, is one of the most commonly used viscous polymers in synthetic tears to accomplish the prolonged ocular surface residency length. Because of its viscosity and mucoadhesiveness, CMC has a long retention time on the ocular surface. It is made by pretreatment of cellulose with sodium hydroxide, combining chloroacetic acid, and adding an alkali catalyst. The molecular weights of this material, however, range from 90,000 to 2,000,000 g/mol. As a viscosity modifier, emulsifier, stabilizing agent, and lubricant, sodium carboxymethylcellulose (SCMC) is frequently employed in the manufacturing of medicinal dosage forms. In addition to being secure for use in medicine, it is inexpensive, abundant, and has a high-water bonding capacity.60

Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose-based formulations

SCMC-based in situ gel

After being injected into the eye and subjected to physiological conditions, a viscous liquid known as an in situ active gel forming system transforms into gels or solid phase. In situ gelation combines the precision and ease of solutions and gels, as well as the latter’s prolonged precorneal retention.61

We created the formulation with the most potential for sustained azithromycin release and effectiveness using pectin and SCMC at 0.5% w/v. Similar to polyacrylic acid, the cellulose ether SCMC exhibits mucoadhesive characteristics. In order to promote ocular bioavailability via mucoadhesion and aid in the creation of the in situ gel, SCMC, a viscosity enhancer, is used. Pectin-based in situ gels may be utilized to extend azithromycin’s duration of action or contact time in the ocular region.62

Hyaluronic acid

The extracellular matrix contains HA, a polymer with a high molecular weight. This non-immunogenic glycosaminoglycan is utilized in ophthalmic medicine for a variety of objectives, including protecting corneal endothelial cells during intraocular surgery, treating dry eyes by replacing tears for vitreous humor, and lengthening the precorneal residence duration of various pharmaceuticals. Diluted sodium hyaluronate solutions, which act as a substitute for tears, have been used successfully to treat severe dry eye conditions. Their primary advantages are their biophysical characteristics that resemble mucin and viscoelasticity, which allow long-lasting hydration and retention. The eye’s surface is also well moisturized. Along with its ability to promote corneal epithelial cell proliferation, HA has also been related to inflammation and wound healing.63

When given topically to the eye, HA stimulates keratocyte proliferation and corneal epithelial migration, which speeds up wound healing. Topical eye drops must be applied on a regular basis. The viscosity required to ensure good efficacy and an extended residence period while delaying the commencement of ocular surface drainage. However, in order to eliminate optical haze and to speed up the production process, which includes sterile filtration, the solutions should not be excessively viscous.64

Hyaluronic acid-based formulations

Hyaluronic acid-modified mucoadhesive liposomes

For more than a decade, liposomes, a type of closed vesicle composed of an aqueous phase and a phospholipid bilayer, have been used to treat eye problems. This approach resulted in regulated medication release and lowered membrane permeability. Liposomes modified with HA function as an eye therapy. Because HA-modified liposomes can be given more often and at lower doses, and because HA-coated vehicles have a longer retention time on the surface of the eye, ocular drug bioavailability is increased.

Hyaluronic acid-based mucoadhesive niosomes

Niosomes, which are non-ionic, self-assembling vesicles, outperformed the replacement system in the following ways: they offer high compatibility, chemical stability, low toxicity, ease of production, and increased solubility and permeability due to the use of surfactants. Mucoadhesion niosomes with HA coatings are being developed. The HA coating aided niosome adherence to mucin. The HA-coated niosomes surpassed solution- or uncoated niosomes in terms of ocular bioavailability and aqueous humor pharmacokinetics. They also improved tacrolimus retention in vivo.65

Oxidized hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel

A hydrogel can be created by combining oxidized HA, CS and glycol. In this study, researchers developed a hydrogel film that can deliver the eye drugs dexamethasone and levofloxacin at the same time. The swelling ratio of the hydrogel films reduced as the oxidized hyaluronic acid (OHA) oxidation level increased. Many bacterial strains were inhibited in their development when exposed to hydrogel sheets containing levofloxacin.66

Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose

According to research, while having a lower viscosity than carbomer, this substance has better mucoadhesive qualities. The gelling capabilities of HPMC and carbopol 980 NF were merged to create a pH-responsive in situ gelling vehicle, serving as a gelling agent for administering drugs to the eye. Additionally, the laboratory examined how hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) impacted puerarin solubility in water and its penetration into the cornea.67 The substance is composed of glucose molecule chain. However, instead of the hydrogen, the material is composed with methoxy and hydroxypropyl side chains of the hydroxyl groups. It is a cellulose ether that is commonly used as a first-line treatment for dry eyes and other ocular surface problems.68, 69

HPMC-based formulations

Ocular film using HPMC

Following the method for administering diclofenac sodium to the eye, CS-based nanoparticles are dispersed on an HPMC-based film. The CS-HA nanoparticles’ zeta potential was discovered to have a negative charge. Encapsulation efficiency was 70%, and the particles were nanometer in size. The diclofenac film viscosity/polymer concentration had a higher viscosity and a slower rate of drug release. When nanoparticles were added to HPMC films, the drug was released gradually and constantly. Drug release and corneal penetration studies demonstrated that diclofenac-loaded nanoparticles have a slower- or longer-lasting drug release.70

HPMC-based ocular insert

Cyclosporin A (CsA) is the most effective in the manufacturing process for the physicochemical analysis and it is loaded with HPMC inserts. Mechanical features such as thickness and wettability have been shown to reduce eye irritation. The CsA concentration in the polymer matrix was uniform throughout. According to the in vitro release studies, the drug continued to leak for up to 20 h. Xanthan gum improves folding endurance and extends the time the medicine is in contact with the ocular layer in addition to increasing the time of CsA production. The cytotoxicity investigation did not show any evidence of harm to the bovine corneal cells, in contrast to the control group.71 The research’s conclusions show that when CsA was added to the anti-inflammatory study in Jurkat T cells activity by reducing interkeukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production (Figure 3, Table 3, Table 4).

Conclusions

Some of the problems with the present formulations result in a very little fraction of active moiety in the posterior section of the ocular region. Due to a shorter residence time, reduced penetration and an absence of optimal viscosity behavior, topical ophthalmic medicine has a lower ocular bioavailability. The viscosity agents employed in ophthalmic formulations can be crucial in extending the active moiety’s precorneal residence time on the epithelial corneal surface. It is challenging for manufacturers to use selected viscosity components at an appropriate concentration in an ophthalmic formulation. Furthermore, the viscosity-improving components are crucial in lowering surface tension (between the formulation and the corneal surface), which improves corneal surface contact time and ocular bioavailability of the relevant formulations.

It has been established that the use of viscosity enhancers is successful in treating the symptoms of dry eye caused by a lack of aqueous tears. Viscous topical ophthalmic solutions provide significant efficacy and prolonged residence time while delaying rapid drainage from the ocular surface. The concentration of the eye solution should be adjusted to minimize viscosity in order to prevent blurry vision. A medication delivery method intended to prolong the duration of drug interaction at the ocular site is known as a viscosity enhancer. Additionally, the viscosity enhancer has been demonstrated to improve corneal absorption by altering the integrity of corneal epithelium. Further developments in ocular medication delivery systems are expected in future in order to improve and preserve eye health, enhance patient compliance, and accomplish superior results in the management of ocular disorders.

Expert opinion

Over the last 2 decades, there have been major advancements in the study of ocular drug delivery, turning away from the use of traditional solutions, suspensions and ointments and towards viscosity-improving in situ gel systems, various inserts, colloidal systems, etc. Even though significantly higher bioavailability and controlled release systems have been achieved with the use of various novel formulation approaches for ophthalmic drug delivery, research is mainly limited to in vitro and in vivo studies, with very few reports on phase I clinical trials. The commercialization of newer dosage formulations is severely constrained by this issue. The physical stability problems linked to vesicular systems, another barrier to the commercialization of innovative dosage forms, need to be resolved through extensive research.

Due to the ability of the medications to penetrate deeper tissues, the use of topical chemotherapy for the treatment of ocular melanoma (uveal, corneal and conjunctival melanoma) is restricted. Owing to the CS capacity to disrupt the deeper corneal layers, as opposed to synthetic penetration enhancers such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), azone compounds, sodium deoxycholate, polycarbophils, etc., it can increase the bioavailability of chemotherapeutic medications. Melanoma cells can be targeted with chemotherapeutic drug-loaded nanoparticles identified with specific moieties, and sustained release can be achieved.