Abstract

In dentistry, fluoride compounds play a very important role in the development of teeth hard tissue. They have been modifying the development of the carious process for many years in accordance with the principles of minimally invasive therapy. Studies have confirmed their effectiveness in the prevention and treatment of carious lesions and erosion of deciduous and permanent teeth, as well as in the dentin hypersensitivity treatment. Typically, each varnish consists of 3 basic components, i.e., a resin usually in the form of mastic, shellac and/or rosin, an alcohol-based organic solvent (usually ethanol) and active agents. In the first-generation varnishes, the active agent is fluorine compounds, most often in the form of 5% NaF, while in second-generation varnishes, the composition is further enriched with calcium and phosphorus compounds in the form of CPP-ACP/CPP-ACPF, ACP, TCP, fTCP, CSPS, TMP, CXP, or CaGP. This influences the bioavailability of fluoride in the oral environment by increasing both its release from the product and its subsequent accumulation in enamel and plaque, promotes more efficient closure of dentinal tubules, and facilitates pH buffering in the oral cavity.

Key words: dental caries, fluoride release, fluoride varnishes

Introduction

Fluoride is a cyclic element widespread in nature, which, due to its high electronegativity and activity, does not occur in elemental form but only in the form of compounds, reacting with almost all other elements, noble gases, and organic and inorganic compounds.1 It belongs to micronutrients, and can be found in supportive tissue within an organism, in the hard tissues of teeth, in the skin, and in hair. In addition, as an element with high biological activity, it often acts as an inhibitor or, less frequently, an activator of many enzymes, affecting the course of protein biosynthesis processes, carbohydrate metabolism or lipid metabolism.2

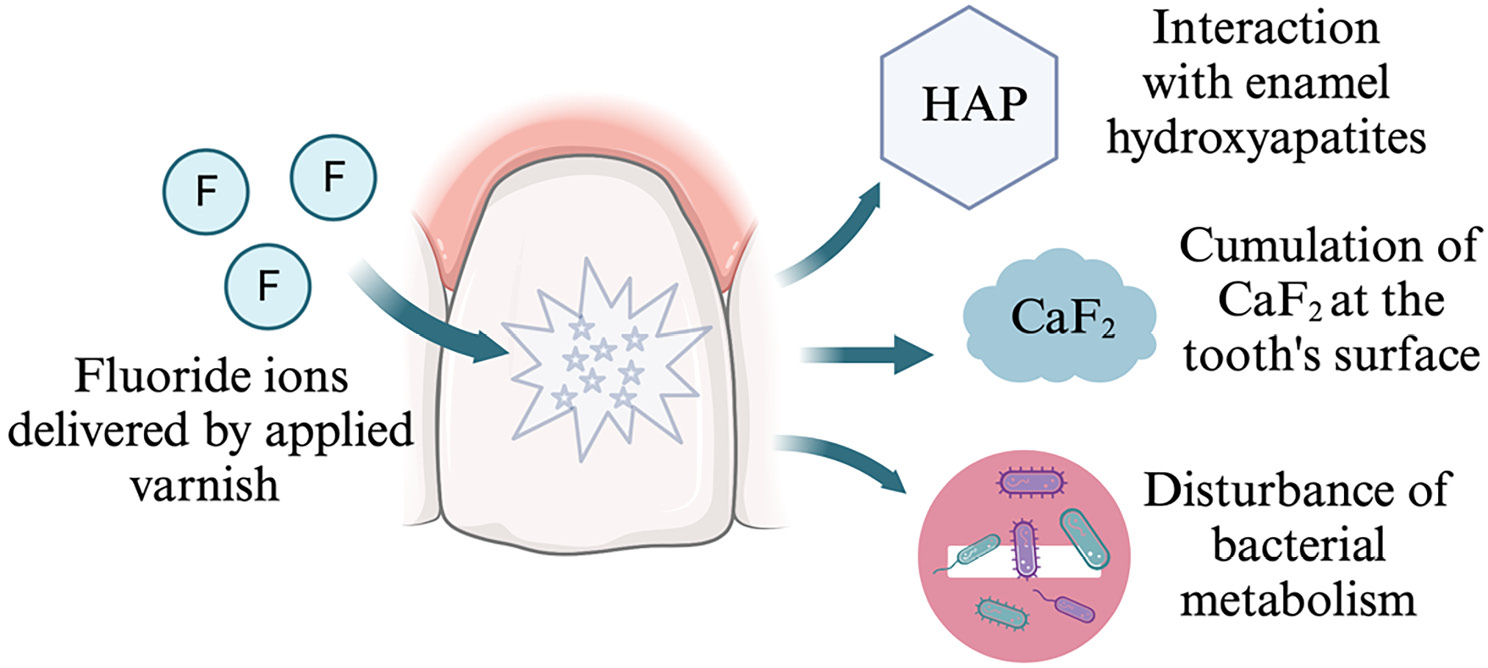

Fluoride-containing compounds are widely used in minimal invasive therapies in contemporary dentistry. Their effectiveness in preventing caries end erosion of primary teeth and treating hypersensitivity in permanent teeth has been confirmed in many reports.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 The role of varnishes is depicted in Figure 1. Furthermore, it is suggested that continuous, repeatable fluoride delivery over time is most advantageous for dental treatment.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 It turns out that the amount of fluoride in the fluids flowing around the teeth in the experimental model above 0.03 ppm already initiates a cariostatic effect.

Fluoride varnishes are materials that contain the highest content of this element and are intended for professional use in dental practices. They facilitate prolongation of contact between tooth tissues and fluoride. Their use in dentistry was first reported in 1964 by German researcher Hans Joachim Schmidt. He used 2% sodium fluoride in an alcoholic solution of natural resin as an alternative to preparations that were aqueous. Clinical studies confirming its effectiveness were published 4 years later,13 resulting in the introduction of the first commercial fluoride varnish to the markets under the name of Duraphat (Woelm Pharma Co., Eshwege, Germany) containing 5% NaF. Promising results contributed to the introduction to the market of newer formulations in subsequent years, i.e., in 1975 Fluor Protector (Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) with 0.9% difluorosilane, in 1984 Duraflor (AMD Medicom Inc., Montreal, Canada) with 5% NaF, or in 1986 Bifluorid 12 (Voco Chemie GmbH, Cuxhaven, Germany) with 6% NaF.14 Approved by the FDA in 1994, they initially functioned as hypersensitivity drugs, and over the years have become a permanent part of dental practice. Numerous meta-analyses showed their therapeutic effectiveness in reducing caries at 46% for permanent dentition and 33% for deciduous dentition, provided they were applied 2–4 times a year.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Similar results were obtained in a study in which the use of fluoride varnish as early childhood caries prophylaxis reduced caries by 25–45%.20, 21

Structure of fluoride varnishes

Fluoride varnishes are available on the market in a wide variety, differing in chemical composition, particle shape and size, consistency and viscosity, which, according to some researchers, affects different fluoride release patterns.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Typically, each varnish consists of 3 basic components, i.e., a resin (often in the form of mastic), shellac and/or rosin in an organic solvent (usually ethanol), and of active agents involved in the remineralization process.29, 30 Shellac and mastic are responsible for the formation of an elastic and hard layer on teeth, which prevents rapid dissolution in saliva. On the other hand, rosin obtained from the oleoresin of dead pine wood or talc oil improves the liquidity of the preparation, which translates into better adhesion to enamel, longer contact time with the tooth surface, the ability to flow onto hard-to-reach surfaces and prolonged release of fluoride ions. In turn, the polyvinyl acetate polymer used in varnishes with complex of casein phosphopeptide and amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) shows very good solubility in aqueous solutions, which can directly affect the dynamics of fluoride ion release.31 Alcohol, undergoing rapid evaporation after exposure to air, leaves free volume, which causes easier contact of the varnish with water and accelerates the release of fluoride.32 The active agents of the first generation of varnishes are usually in the form of neutral or acidified 5% NaF containing 2.26% fluoride ions (22,600 ppm of fluoride), 1% difluorosilane containing 0.1% fluoride ions (1,000 ppm of fluoride) or 6% NaF combined with 6% CaF2 (56,300 ppm of fluoride). TiF4-containing varnishes can also be found, while they are still seen as experimental formulations requiring continued in vitro and in vivo studies.33, 34, 35 In the literature, the formation of calcium fluoride after application of 2% neutral NaF has been compared with acidified fluoride preparations, which evidently showed an advantage for the latter in terms of the amount of CaF2 deposited on the enamel surface.36, 37 This is explained by increased affinity of the released fluoride to the enamel in an acidic environment compared to neutral pH. According to many researchers,23, 38, 39, 40, 41 in the oral environment, the amount of available calcium and phosphate ions is insufficient to bind the large amounts of fluoride obtained after fluoride varnish application. For this reason, so-called second-generation varnishes enriched in Ca2+ and PO43− ions in the form of, e.g., complex of casein phosphopeptide and amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP, CPP-ACPF), amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP), tricalcium phosphate (TCP – tricalcium phosphate – Ca3(PO4)2), active form of tricalcium phosphate (fTCP), sodium-calcium phosphosilicate (CSPS or so-called bioactive glass), sodium trimetaphosphate (TMP), xylitol-coated calcium phosphate (CXP), or calcium glycerophosphate (CaGP).28, 35, 42, 43, 44, 45 Their presence is believed to have a significant effect on the bioavailability of fluoride in the oral environment by increasing its release from the product, facilitating its accumulation in enamel and plaque, closing dentinal tubules more effectively, and buffering oral pH. However, there is still no conclusive evidence as to which of the aforementioned compounds works best.25, 26, 28, 37, 39, 42, 43, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 According to Karlinsey et al.,51 the addition of TCP increases the effectiveness of fluoride without compromising its bioavailability. This is explained by the fact that during the manufacturing process, a protective fumar barrier is formed around the Ca2+ ions, preventing the ions from being deactivated during storage. Contact limited to saliva causes the barrier to dissolve, resulting in the release of both calcium and fluoride ions, the latter in significantly higher amounts compared to non-enriched varnishes.48, 52, 53 Research conducted by Alamoudi et al.54 showed an increase in the microhardness of the enamel surface treated with varnish from TCP, and Elkassas et al.52 reported greater remineralization efficiency following reducing its roughness. Another available compound is the CPP-ACP/CPP-ACPF complex, which includes a milk-derived protein that is a source of readily available calcium ions and phosphate ions. Casein phosphopeptides (CPP), with the help of phosphoserine sequences, stabilize amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) and, after contact with saliva, help it attach to the surface of enamel or plaque.28, 45, 55 This was confirmed by in vitro research38, 56 showing CPP-ACP nanocomplexes attached to supragingival plaque, as well as to the surface of Streptococcus mutans bacterial cells by means of electron microscopy. By buffering the pH of the biofilm, free Ca2+ and PO42– ions dissociate, thus not only acting as a reservoir of bioavailable ions, but also maintaining the supersaturated state of saliva relative to the surface of the enamel.57 Some researchers believe that the enrichment of the varnish with the CPP-ACP complex is the best technology that allows a stable combination of high concentrations of calcium, phosphate and fluoride ions with the tooth surface and plaque.23, 38, 39, 43, 50, 58, 59, 60, 61 In addition, Bakry et al.62 observed that the application of MI Varnish (GC, Tokyo, Japan) with CPP-ACP complex is followed by a significant reduction in demineralization and an increase in enamel microhardness. This was confirmed by the study by Świetlicka et al., in which it was shown that 24 h after application, fluoride varnish with CPP-ACP induced partial regeneration of the previously damaged enamel surface, activating the formation of a new honeycomb-like layer.63 On the other hand, according to Yapp et al.,64 a better solution is the introduction of CXP (xylitol-coated calcium and phosphate) ions into the varnish, i.e., calcium and phosphate ions coated with xylitol and suspended in a permeable resin, which enables their uniform and prolonged release and enhances the antimicrobial effect. According to the manufacturers,65 such an enriched varnish can provide 4 times more fluoride compared to others, with the maximum release occurring in the first 4 h after application.

In addition to these 3 main ingredients, manufacturers may also add colorants, sweeteners (e.g., saccharin sodium), stabilizing and adhesion-enhancing agents,35 as well as xylitol with antimicrobial properties, chlorhexidine with antimicrobial and remineralizing properties, or arginine and chlorhexidine with antibacterial, remineralizing and pH stabilizing properties.43

Reviewing the literature, we can find new experimental varnishes that are undergoing clinical evaluation all the time. Pichaiaukrit et al. evaluated in 2019 in vitro the effect of chitosan, a linear copolymer of D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, on fluoride release.66 Comparing fluoride varnishes differing only in the amount of chitosan, it was found that the increase in fluoride release was related to the increase in polymer concentration. The highest values were obtained after 1 h, which significantly decreased after 2 h after application, with slow but steady fluoride release continuing up to 6 h. Unfortunately, fluoride varnishes with chitosan were cytotoxic to human gingival fibroblasts. Table 1 lists examples of first- and second-generation fluoride varnishes with information on their composition.

Mechanism of action of varnishes and fluoride

Fluoride ions released by fluoride varnishes have a direct effect on the processes occurring on the surface of the enamel in the oral environment. More specifically, they inhibit demineralization, promote remineralization and interfere with the adhesion and metabolism of carious bacteria.12, 14, 15, 29, 44, 73, 74

Two types of reactions of fluoride with enamel occur depending on the concentration of the preparation used.75 At low concentrations of no more than 50 ppm, fluorohydroxyapatite is formed with simultaneous acidification of the environment, which follows the reaction described below (Reaction 1).

Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 + F– + H+ → Ca10(PO4)6(OH)F + H2O

The fluorohydroxyapatite thus formed is very strongly bound to the outermost layers of the enamel. In the literature, it is often referred to as bonded fluoride, which can only be lost if the entire tissue is abraded or completely dissolved. If the concentration of fluoride is greater than 100 ppm on the enamel surface, small granules of calcium fluoride form in the plaque and acquired membrane, perceived as loose, unbound fluoride,14, 37, 40, 42, 43, 56, 74, 76, 77, 78 as illustrated by the reaction below (Reaction 2).

Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 + 20F– + 8H+ →

10CaF2 + 6HPO42– +2H2O

Fluorides react with hydroxyapatites of the enamel by replacing hydroxide ions. As a result of this reaction, some part of hydroxyapatites transform into fluorapatites, which have better crystalline properties, and are more acid-resistant. In the apatite, strong ionic bonds between fluoride and the amine group of the organic enamel matrix are formed, which contributes to greater stability of fluorapatite crystals. Fluoride may also react with apatite by stimulating the growth of fluorapatite crystals. Moreover, it may cause apatite dissolution and forming calcium fluoride. The formation and stimulation of fluorapatite growth may occur during frequent exposure to low fluoride concentration in the solutions (below 0.1%). The role of fluoride delivered through application of varnish at the tooth’s surface is showed in Figure 2.

The bacteriostatic and/or bactericidal effect is achieved by reducing plaque deposition by disrupting bacterial adherence to the acquired membrane and altering bacterial metabolism by inhibiting enolase activity, reducing glucose transport into the cell and storage, interfering with the synthesis of extracellular and intracellular bacterial polysaccharides, decreasing the amount of lactic acid produced, decreasing the activity of cellular phosphatases responsible for the hydrolysis of phosphate esters, and disrupting the transport and accumulation of cations in cells.9, 37, 74

Fluoride varnish application involves the use of high concentrations of fluoride salts suspended in a resin that allows them to persist for some time on the tooth surface. The basic technology involved in the construction of F varnishes is to use very high concentrations of fluoride salts, usually at 50,000 ppm NaF (22,600 ppm of fluoride) in a resin varnish that stays on the tooth surface for several hours. During the dwell time, saliva washes over the varnish and dissolves the fluoride salts, allowing fluoride ions to diffuse out of the varnish and be absorbed into the fluoride reservoirs in oral fluid tissues, plaque and teeth. Over time, fluoride ions are re-released from these reservoirs.44 Released fluoride ions accumulate in higher concentrations (above 100 ppm) both on the enamel surface and in the enamel itself, as well as in plaque. The presence of fluoride attracts calcium and phosphate ions from saliva or from dissolved hydroxyapatite, forming small calcium fluoride crystals with embedded phosphates.14, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44, 74, 76, 77, 78 Since pure CaF2 crystal is cubic rather than spherical, the resulting spherical deposits are described as calcium fluoride-like compounds, which on the one hand block acid diffusion, and on the other hand form a fluoride reservoir that is stable and insoluble in neutral pH environments. Phosphate ions increase its solubility compared to pure CaF2.24, 79 With a decrease in pH, the membrane coating is dissolved and the release of fluoride ions and their incorporation into the enamel structure occurs. A decrease in fluoride concentration below 100 ppm and an increase in pH results in saturation of the enamel relative to the surrounding fluid and inhibition of the process described above.12, 29, 37, 40, 42, 44, 53, 74, 76, 80 Following the application of the varnish, more fluoride is retained on the demineralized rather than the healthy surface, contributing to the activation of repair processes in the enamel.3, 81

The formation of CaF224, 25, 34, 40, 50, 67, 82, 83 is influenced by fluoride ions at sufficiently high concentrations, as well as calcium and phosphate ions presence in the oral cavity.23, 38, 40, 41, 56 According to Attin et al.,84 the supply of these ions in second-generation varnishes results in the deposition of larger amounts of calcium fluoride on the enamel surface, which in turn enhances the therapeutic effect.23, 38, 48, 49, 60, 78, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92

Clinical use of fluoride varnishes: indications, scheme, contraindications, and method of application

Varnish is defined as a professionally, topically applied fluoride compound. Its topical application is meant to slow down the release of active substances, including oxidative agents or chlorhexidine.93 Varnishes have properties that facilitate their adhesion to the tooth surface. In comparison to sealants, fluoride varnishes are claimed to be easier to apply. In contrast to the multi-step technique of sealant application, varnishes can be successfully applied without etching or overdrying the surface of the tooth.94

Application and spreading of fluoride varnishes on tooth surfaces is usually performed with small brushes or cotton pellets. In the process of application, the clinician applies around 0.30–0.75 mL of varnish per single tooth. Additionally, the clinician may soak the dental floss in a varnish and apply it between teeth to cover hard to reach interdental spaces. Prolonged adhesion to the enamel enables the varnish to constantly release the fluoride, lowering long-time sensitivity and vulnerability of the tooth toward bacterial activity and generally caries.29 The whole process should take about 1–4 min, which is dependent on number of teeth that need to be covered. The indications after successful application of fluoride varnish are as follows: Patient should avoid eating for around 2 h and in order to allow varnish to remain longer on the tooth surface, tooth brushing should be avoided on the same day, after which it should be continued. Fluoride varnishes have no age restrictions. For moderate risk, they should be applied twice a year, while for high risk up to 4 times. Disposable doses of fluoride varnish containing 5% NaF (22,600 ppm of fluoride) are 0.10 mL for infants and 0.25 mL for children over 1 year old. Contraindications to the use of fluoride varnish include bronchial asthma, stomatitis and necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis.

The use of fluoride varnishes in dentistry is now recommended by international dental organizations and societies, e.g., European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (EAPD), American Dental Association (ADA), American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), IAPD International Association of Paediatric Dentistry (IAPD), World Dental Federation (FDI), or World Health Organization (WHO).95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101

According to ADA experts, in adults at increased risk of developing caries, including root caries, professional prophylaxis should include the application of 2.26% fluoride varnish 2–4 times a year or the use of acidified fluorophosphate gel (1.23%) 2–4 times a year.102 Fluoride varnishes possess many advantages which make it one of the best ways of topical application. In general, they are considered safe and acceptable.103 Their prolonged, slow release of fluoride allows teeth to be exposed to higher doses without the risk of overdose. The application is fast and simple, without any need of additional drying. Prior teeth prophylaxis is not mandatory before application. Rapid setting time makes it an ideal material even for younger children or patients with gagging reflux.14 Indications of topical fluoride varnish applications are mainly dental prophylaxis treatment of incipient caries or root caries. Hypersensitivity of teeth or roots is another indicator where fluoride varnish can act as a pain relief. Varnishes are indicated for use in patients with bad hygiene that has no prognosis of getting better, including handicapped and senile patients or children. They are particularly recommended for children using orthodontic appliances, adults using prosthetic restorations and patients with decreased salivary secretion.104

Among the contraindications, there are confirmed statuses like bronchial asthma, stomatitis or necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Each applied dose of a varnish contains up to 0.2 g of ethanol, and therefore usage during pregnancy or lactation is not recommended. Application of fluoride varnish may occasionally cause temporary discoloration of teeth after contact with fluoride, lasting around 24 h after the outer layer of varnish is removed with brushing.29 There is a possibility of allergy to fluoride varnish, which can cause a burning sensation in the mouth, eventually causing dermatitis or stomatitis if the varnish had contact with either skin tissue or oral mucosa. A lot of varnishes, e.g., Duraphat® (Colgate Oral Care, Sydney, Australia), contain rosin. Children who were hospitalized during previous 12 months due to severe asthma or allergies or who are allergic to patches may be at risk of an allergic reaction to rosin. In such cases, usage of varnish without rosin should be considered (approved for caries prevention in the UK) or alternative age-appropriate fluoride preparations should be suggested (e.g., fluoride mouthwash or toothpaste with a higher fluoride concentration). Likewise, fluoride varnishes containing the CPP-ACP complex are not recommended for patients allergic to milk. Swallowing the topical fluoride varnish may result in elevation of plasma fluoride level, yet such increase is lower than when compared to fluoride gels.105

Discussion

The effectiveness of the cariostatic action of fluoride ions can be attributed, on one hand, to their multidirectional effect on the carious process.106, 107, 108, 109, 110 On the other hand, it affects the hard tissues of the tooth from mineralization during development to external protection in the oral environment. Fluoride released from fluoride varnishes increases its concentration in both saliva and plaque, interacts with enamel hydroxyapatites, interferes with bacterial metabolism, and accumulates on the tooth surface in the form of CaF2. These deposits, according to Øgaard et al.,24 could be observed in vitro for up to 4 months after application, while in vivo, due to the processes involved in chewing, swallowing, speech, and individual hygiene procedures, the time period of CaF2 deposit removal was definitely shorter when compared to in vitro observations, reaching up to a maximum of 3 days.111 According to Tenuta et. al.,77 it is the amount of calcium fluoride formed that will have a direct impact on the long-term maintenance of higher fluoride levels in the mouth and the effective long-term anti-carious effect. Other researchers40, 67, 82, 83 emphasize the importance of calcium and phosphate ions present in the mouth as a factor that has a significant impact on the amount of fluoride captured and bound.24, 25, 34, 50

Despite a very large number of studies conducted both in vitro and in vivo, there is still no clear opinion regarding the choice of the best fluoride varnish. Numerous experiments have shown that all varnishes of both the first and second generation applied to tooth surfaces release fluoride ions and cause them to accumulate in the enamel and plaque.23, 25, 46 In in vitro studies, fluoride release was greatest during the first few hours after application, then decreased over time, with some investigators observing this on the 1st day after application46, 69, 112 and others within 3 weeks.25, 50 The highest increase in fluoride was usually measured either after the 1st46, 112 or the 2nd hour after application.25, 113, 114 Cumulative fluoride release, even for varnishes containing the same amount of fluoride, was not uniform and was likely due to differences in formulation, consistency and viscosity of the formulations.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 115 Shen and Autio-Gold115 obtained lower cumulative fluoride release in artificial saliva from Duraphat® (Colgate Oral Care) compared to Duraflor® (AMD Medicom Inc., Montreal, Canada) and CavityShield® (3M ESPE Dental Products, St. Paul, USA) (all 3 varnishes with 5% NaF), but for all, the decrease in ion emission between 7 h and 213 h of the experiment was similar.

Under in vivo conditions, the decrease in fluoride release was faster due to the effects of saliva on fluoride leaching and retention, as well as due to cheek and tongue muscle work, chewing, diet acidity, or hygiene treatments, but the pattern overlapped with in vitro studies. Most fluoride was released during the first few hours after application; in some studies,46, 112 it was the 2nd hour of the study, and in others the first 4 h.36, 58 A study by Piesiak-Pańczyszyn and Kaczmarek46 showed a significant increase in salivary fluoride release during the first 2 h after application, which decreased with time, with the highest increase in the 1st hour – more than 15 times the initial value, in the 2nd hour slightly less, representing 9 times the initial level, and decreasing in the 168th hour of the experiment to a value oscillating near the initial value and corresponding to the cariostatic level. Comparing first- and second-generation varnishes with each other, it turns out that opinions on their effectivness and the factors affecting them are divided.45 Based on data from the literature, one can find both works that, evaluating the amount of fluoride ions released, as well as the composition and mechanical properties of varnish-treated enamel surfaces, showed the superiority of second-generation varnishes over the first one,23, 38, 45, 46, 48, 49, 60, 78, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 112 as well as those that did not show these differences28, 76, 78 or even studies reporting the higher effectiveness of non-enriched varnishes.23, 42, 53

In a number of comparative studies, the best performing varnish was the second-generation one containing the CPP-ACP complex, for which the highest cumulative fluoride release and the largest increases in released fluoride over time were recorded.23, 46, 85, 112 In addition, it is also noteworthy that this release proceeded most dynamically in the initial phase, causing the release of more than 90% of the total available amount of fluoride applied in the varnish in a fairly short time (up to 24 h).46, 112 This was confirmed in a laboratory study performed by the ADA in 2015.116 This study considered 7 varnishes, from which only 2: – MI Varnish (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (with CPP-ACP complex) and Prevident® varnish (Colgate Oral Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Canton, USA) (with 5% NaF and xylitol) – released almost 100% of the available fluoride within the first 6 h after application, while the other 5 reached levels between 29% and 53%. In contrast, Milburn et al.50 showed in vitro that CXP-containing Embrace™ varnish (Pulpdent, Watertown, USA) released as much as 10-fold more fluoride in the first 4 h after application than Duraphat® (Colgate Oral Care), Enamel Pro Varnish (Premier Dental Products, Plymouth Meeting, USA) and Vanish (3M ESPE Dental Products). There are other papers that show higher amounts of fluoride ions released from varnishes with amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP).25, 26, 117 In a study by Jablonowski et al.,25 highest cumulative release of fluoride and highest rate of release were recorded for the Enamel Pro varnish with the addition of ACP for timeframe up to 3 weeks after application. Limit of detection in the referenced work oscillated around 4th week of the experiment for Enamel Pro Varnish (Premier Dental Products) compared to Duraphat® (Colgate Oral Care) and Clinpro XT (3 M ESPE Dental Products) varnishes, which reached limit of detection after approx. 6–7 weeks. It translates to a conclusion that varnish containing ACP in relatively short time released all available fluoride, causing its high concentration in the initial phase, which is considered critical.

In the case of second-generation varnishes, fluoride release is often observed in 2 phases, which was decribed by Pichaiaukrit et al.66 The phase of initial rapid release of large amounts of fluoride usually lasts until the first 4 h after application, depending on the varnish; between 12 h and 24 h, a steady, slower increase in fluoride commences, reaching a plateau.34, 46, 50, 112 In line with previous opinions26, 44 that a sufficiently high initial concentration of fluoride allows the formation of more calcium fluoride on the enamel surface and facilitates its binding to tooth tissues, and because the retention time of the tooth varnish is limited under in vivo conditions, such fluoride release characteristics can have a pronounced impact on the therapeutic efficacy of the applied agent. Some researchers also noted the highly significant effect of medium pH on the amount of fluoride ions released.46 In the studies by Piesiak-Pańczyszyn and Kaczmarek46 and by Piesiak-Pańczyszyn et al.,112 the level of fluoride released for both first (Duraphat®; Colgate Oral Care) and second-generation varnishes: MI Varnish (GC Corporation) and Embrance Varnish (Pulpdent, Watertown, USA) was significantly lower in neutral environments than in pH = 4 and pH = 5 environments, as confirmed in post hoc tests. In addition, regression analysis showed that the acidity of the artificial saliva had a greater effect on fluoride ion release than time since application. On the other hand, Ten Cate et al.,37 evaluating the enamel surface after application of 2% neutral NaF compared to acidified fluoride preparations, found the presence of significantly higher amounts of CaF2 in the latter case. Similar conclusions were obtained in the Fluor Protector study.36, 37

Fluoride varnishes, according to current knowledge, are the safest and most effective means in the treatment and prevention of tooth decay and hypersensitivity.118 Despite the fact that they contain almost twice as much fluoride as the gels and foams used, and more than 15 times as much fluoride as everyday toothpastes, they do not entail health risk.119 The most commonly used fluoride varnishes in dentistry are those with concentrations of 5% NaF, which is equivalent to 22,600 ppm of fluoride.102, 119, 120 Indeed, it has been shown that the maximum fluoride concentration in serum after application of varnish with 5% NaF in young children is only 1/7 of the maximum values found after application of APF gel with 1.25% NaF.121, 122 This is due to the ability to apply the product very precisely to the teeth, as well as its adherence to the enamel surface, which prevents unintentional swallowing.122 An analysis of the number of adverse events reported to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) confirmed that the use of fluoride varnish should be considered safe in the systemic aspect.123 On the other hand, reports of varnish cytotoxicity appearing in the literature draw attention. Due to the close contact of fluoride varnish with enamel, dentin or adjacent soft tissues including the gingival mucosa, it is necessary to rule out cytotoxicity prior clinical use. Evaluation of the possible cytotoxic effect on human tissues caused by fluoride varnishes is important for the health of oral cavity tissues.14, 124, 125, 126

Biocompatibility of materials that are prepared to be used clinically in dentistry is evaluated using primary human cells, including fibroblast cells or odontoblasts cells; e.g., Sengun et al.127 and Hoang-Dao et al.128 confirmed evaluating cytotoxic effects on primary gingival fibroblasts, as well as pulp fibroblasts from dentin slice, due to the fact that both of them are directly exposed during the procedure of fluoride varnish application. In such evaluations, it is extremely important to determine the cytotoxicity of a specific agent in vitro. Cytotoxicity can be properly measured only when there is direct contact between the specific material and gingival cells. Hoang-Dao et al.128 confirmed that toxicity of given material is generally lower on dentin slice when compared to gingival fibroblasts. It can be explained by the buffering capacity of dentin.129 There is also additional risk of swallowing fluoride varnishes, which should be avoided because of renal toxicity risk.18 Moreover, it is very important to follow the clinician’s recommendations regarding the dosage of fluoride varnishes. Prolonged inappropriate effects of fluoride varnishes on soft tissues in the oral cavity can cause, although rare and preventable, acute topical toxicity involving oral mucosa irritation.130, 131

Conclusions

Despite many studies conducted both in vitro and in vivo, we still do not know all the mechanisms affecting the effect of fluoride on dental hard tissues, nor are we able to identify all the relevant variables that may intensify or limit this effect. In addition, in light of emerging information about the local negative effects of fluoride varnishes on soft tissues, it is necessary to continue experiments to maximize efficacy and safety.