Abstract

• Plant-derived virus-like particles (pVLPs) provide a sustainable and multifunctional nanoplatform for drug delivery, enhancing drug solubility, bioavailability and controlled therapeutic release.

• Plant virus capsid proteins act as natural nanocages that enable efficient drug encapsulation, surface modification and targeted delivery through chemical or genetic engineering.

• pVLPs integrate biotechnology and materials science, offering a biocompatible, cost-effective and eco-friendly alternative to synthetic polymer nanoparticles (NPs) in nanomedicine.

• This review article explores the development, biomedical applications, challenges and future prospects of plant virus-based nanostructures in controlled drug delivery and therapeutic innovation.

For several decades, conventional treatments for chronic and degenerative diseases have been constrained by technological limitations, particularly those related to the physicochemical properties, stability and bioavailability of therapeutic molecules, as well as the efficiency of their delivery systems. Medical polymers are widely used in drug delivery to enhance the solubility, stability and controlled release of therapeutic agents, and they can be engineered into nanoparticles (NPs) derived from either natural or synthetic materials. Toward the end of the 20th century, the use of plant viral capsids as supramolecular structures for the packaging and controlled release of therapeutic compounds emerged, introducing a versatile, sustainable and cost-effective strategy that has progressively gained scientific and clinical relevance. Capsid proteins (CPs) derived from plant viruses can act as nanocages for drug encapsulation and delivery, and they can be surface-modified or functionalized with a wide range of biomolecules, including peptides, carbohydrates, functional groups, proteins, and oligonucleotides, through either chemical conjugation or genetic engineering approaches. This review explores the historical development, current biomedical applications, inherent challenges, and future prospects of plant-derived virus-like particles (pVLPs).

Key words: biopolymers, nanomedicine, drug delivery systems, plant viruses, nanocapsules

Introduction

One of the main challenges in the therapeutic management of a wide range of human diseases is maintaining the structural integrity and biological activity of drugs while ensuring their specific, efficient and controlled delivery to target cells and tissues. Nanomedicine, an emerging interdisciplinary field, focuses on the design and development of nanoscale structures for therapeutic, diagnostic and theranostic applications, thereby enhancing the stability, efficacy and overall performance of therapeutic agents. These nanostructures, commonly referred to as nanoparticles (NPs), are typically produced through chemical or physical synthesis methods that require considerable technical expertise, specialized equipment and high-purity chemical reagents. Consequently, their production is often associated with high costs and substantial generation of hazardous waste.1 In contrast, naturally derived NPs are assembled from polymers of biomolecules such as sugars, lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins, offering lower production costs and greater environmental

sustainability.

Among these, virus-like particles (VLPs) are noninfectious, protein-based supramolecular structures that can be produced in various organisms or host cells.2,3 Virus-like particles produced in plants (pVLPs) provide safe and cost-effective platforms for biomedical applications. In contrast to the production of animal pathogenic viruses, the generation of plant pathogenic viruses for pVLP production does not require high-level biosafety facilities or specialized containment measures and, in most cases, is exempt from strict bioethical regulations.

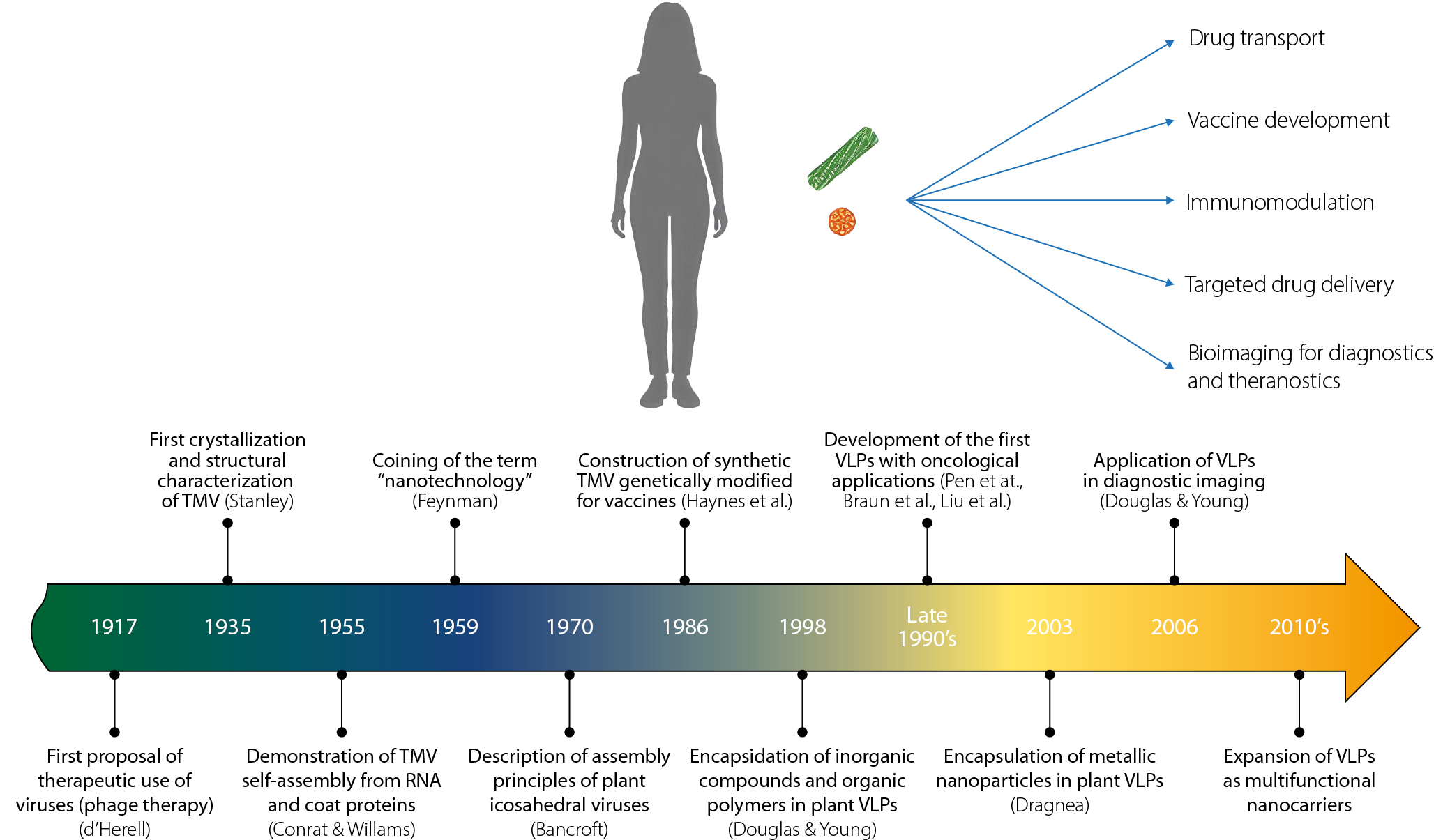

Moreover, large-scale production in plants is relatively simple, scalable and economically viable, supported by well-established agroinfiltration and transgenic expression strategies. These advantages make pVLPs highly attractive candidates for the development of vaccines, drug delivery systems and diagnostic tools, combining biosafety, high yield and structural fidelity.3 Since the beginning of the 21st century, pVLPs have attracted growing interest as drug delivery systems due to their biocompatibility, monodispersity and ability to encapsulate or display therapeutic molecules. Numerous comprehensive reviews have been published, showcasing the broad range of applications for pVLPs.2–7 However, these studies have not addressed the historical challenges and development of these supramolecular structures in nanomedicine. The present review aims to highlight the historical evolution of pVLPs as nanocarriers of bioactive molecules.

Materials and methods

The literature analyzed for this work was retrieved from the PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus databases. To maximize the scope of relevant sources, no temporal restrictions were applied to the articles and studies reviewed. The search strategy included terms such as “plant virus,” “virus-like particle,” “plant virus-like particle,” “plant virus capsid,” and “plant virus protein nanocages.” Nevertheless, the most significant contributions considered in this review are derived from original studies published from the 20th century to the present.

A total of 111 references were selected after applying inclusion criteria that considered only peer-reviewed publications presenting relevant and original contributions (excluding replications of previous studies or works with minor variations). The selected articles were carefully evaluated and mapped along a timeline, with 11 identified as representative historical milestones. In addition, other selected works were analyzed in relation to key concepts that have guided the evolution of medical perspectives, as well as current applications and future prospects.

Early development of the concept of viruses as potentially therapeutic tools

With the advancement of medical knowledge during the 18th and 19th century, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses were exclusively considered infectious agents capable of affecting both animals and plants. This view persisted for almost 3 centuries, until the introduction of concepts such as microbiota – though mentioned since the 20th century, it was widely popularized in the 21st century – which redefines the relationships between host and pathogen. It is now recognized that some microorganisms that are pathogenic to certain species can be harmless, or even beneficial, to others, establishing cooperative consortia resulting from long evolution process.8,9 During the past century this new paradigm allowed for a revival and expansion of Félix d’Herelle’s vision, who in the early 20th century proposed the use of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) as specific antimicrobial therapeutic agents, without affecting human health.10,11 Although his proposals initially did not succeed, by the end of the last century and up to the present day, phage therapy has a broad research focus12 resulting in the commercial use of phages approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2006.13 With this new approach, the idea of using viruses as polymeric systems for therapeutic purposes has increased in recent years.

Another important concept that contributed to the development of VLPs for drug delivery was the use of viral particles in vaccine generation. From the smallpox vaccine developed by Edward Jenner in the late 18th century to the end of the 20th century, viruses were utilized in vaccine production, broadening the understanding of viral particles as therapeutic tools.14

By the 1980s, novel strategies emerged based on the encapsulation of genetic material and the use of VLPs for vaccine development, establishing one of the earliest precedents for employing viruses as carriers of therapeutic agents.15,16 In particular, plant pathogenic viruses have demonstrated remarkable potential in biomedical applications, and with ongoing advances in nanotechnology and molecular biology, their capacity for therapeutic delivery continues to expand.3,10,17,18

What is nanotechnology and where was it born?

Although it is difficult to precisely define the boundaries of the “nano” classification, the term “nano” is generally used to describe structures or molecules ranging in size from 1 to 200 nanometers (nm), whereas nanotechnology refers to the application of such materials in various scientific and industrial contexts. Nanoscience, in turn, focuses on the study, design and generation of structures at the nanoscale.1,19–21

When these findings are applied to address specific problems, the field of nanotechnology emerges. The term ‘nanotechnology’ was first introduced in 1959 by physicist Richard Feynman during the annual meeting of the American Physical Society.22 However, it was in 1974 that Norio Taniguchi formally defined it as a set of tools and techniques for the separation, consolidation and formation of materials at the atomic or molecular level.23

Building on these principles, nanotechnology has advanced toward the development of nanostructures through 2 main approaches: the “top-down” and “bottom-up” methods, each with distinct implications for quality, precision and production costs. Although historical records indicate the use of NPs as early as the 4th century in the Roman Empire, true mastery of nanotechnology – including its synthesis, modeling, modification, and application – has emerged only within the past few decades.

A major turning point was the development of the scanning tunneling microscopy (STM), a technique that enabled the visualization and manipulation of individual atoms. In 1983, the STM was used to reconstruct the surface of silicon (111)-7×7, and in 1990, a team led by Don Eigler at IBM manipulated 35 xenon atoms on a nickel surface to form the company’s logo.

These milestones demonstrated, for the first time, the ability to control matter at the atomic level, sparking global scientific interest in the manipulation of NPs.24–26 Both nanoscience and nanotechnology are relatively recent disciplines, as work at the nanoscale requires techniques that have only become available in the past few decades. Both fields are expanding rapidly and have revealed enormous potential for the development of future technological applications.5,27

Bio-nanomedicine

Initially, nanotechnology focused on addressing challenges in the chemical sciences, such as the development of new materials for industrial applications. However, its uses and applications soon expanded across multiple disciplines. In particular, nanomaterials began to offer solutions to long-standing problems in medicine, serving as strategies for the transport of poorly soluble drugs and for targeted delivery to hard-to-reach sites such as the brain and tumors.5,25,28

From the applications of classical nanotechnology across various scientific fields, modern nanotechnology emerged, integrating principles from chemistry, electronics, physics, and biology.29–34 In the biological sciences, advances in biomaterials and biomolecular research have been particularly beneficial, enabling the development of biologically derived NPs with strong potential for medical and therapeutic applications.19 One of the most important properties of biomaterials is their biocompatibility, i.e., their ability to avoid activating the immune system, which makes many nanosystems ideal for therapeutic applications.35–39 This is particularly relevant for NPs that structurally resemble viruses.18,40–42

The term ‘nanomedicine’ was first coined in the 1990s by Eric Drexler and collaborators in the book Unbounding the Future: The Nanotechnology Revolution,43 and was later formally defined in 1999 in the book Nanomedicine.44 Since then, the discipline was consolidated as a science with the incorporation of nanomaterials into therapeutic strategies.

Despite its relatively recent origin, nanomedicine has undergone rapid expansion driven by technological advances. One of its most promising branches is bionanomedicine, which applies nanotechnological methods and biomaterials for the diagnosis, monitoring and treatment of diseases at the cellular level. This approach focuses on the interaction and modification of biomolecules such as extracellular vesicles, proteins, mRNA, and viral particles.1,41,45–47

Virus-like particles

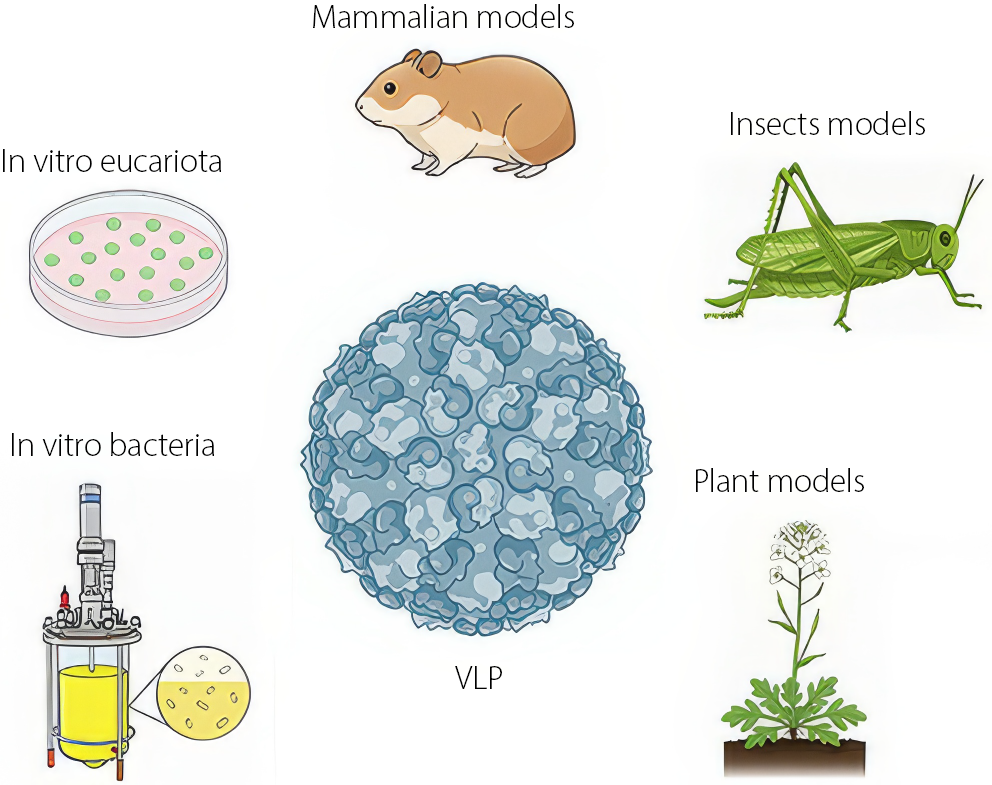

Virus-like particles are natural nanosystems derived from native viral structures that lack infectious capability. These NPs can be produced using a variety of methods and expression systems, including cultivation in plant, mammalian, insect, or bacterial hosts. They can also be generated recombinantly through genetic engineering and molecular biology techniques (Figure 1).

The capsid proteins (CPs) that make up the VLPs are quite resilient, measuring only a few nanometers, have the ability to self-assemble and are biocompatible. The self-assembly capability of the CP allows for the trapping and transport of drugs in VLPs to prevent premature degradation and facilitate their delivery while improving bioavailability in the system.6,48,49 Since the early 21st century, a wide variety of drugs and other therapeutic agents have been encapsulated using the proteins that form the capsid of viruses as nanocages.50–53

One of the first viral particle systems for the delivery of molecules was developed by Zhou et al. using papillomavirus to activate the immune response against tumor models with defined epitopes.51 Subsequently, Braun et al. used polyoma VP1 to encapsulate oligonucleotides and DNA plasmids,54 and in 2000, a system based on the capsid of the papillomavirus was used to transport epitopes and activate the cytotoxic response of T lymphocytes, inducing an improvement in the immune response against the tumor.55 In the following years, VLPs began to be used for the packaging of therapeutic molecules targeting cancer by various research groups with distinct approaches, primarily focusing on disease contexts in which dosage, solubility and specificity represented the greatest challenges.2,6,7,30,56–58

The loading of VLPs can occur through electrochemical processes that promote the assembly of the CP around the therapeutic cargo or through pH-induced pore opening, which allows the cargo to be adsorbed. However, one limitation of VLPs is that the cargo must be compatible with the electrostatic charge and internal cavity diameter of the particle, restricting the number and size of molecules that can be encapsulated.59–61

Virus-like particles based on plant viruses

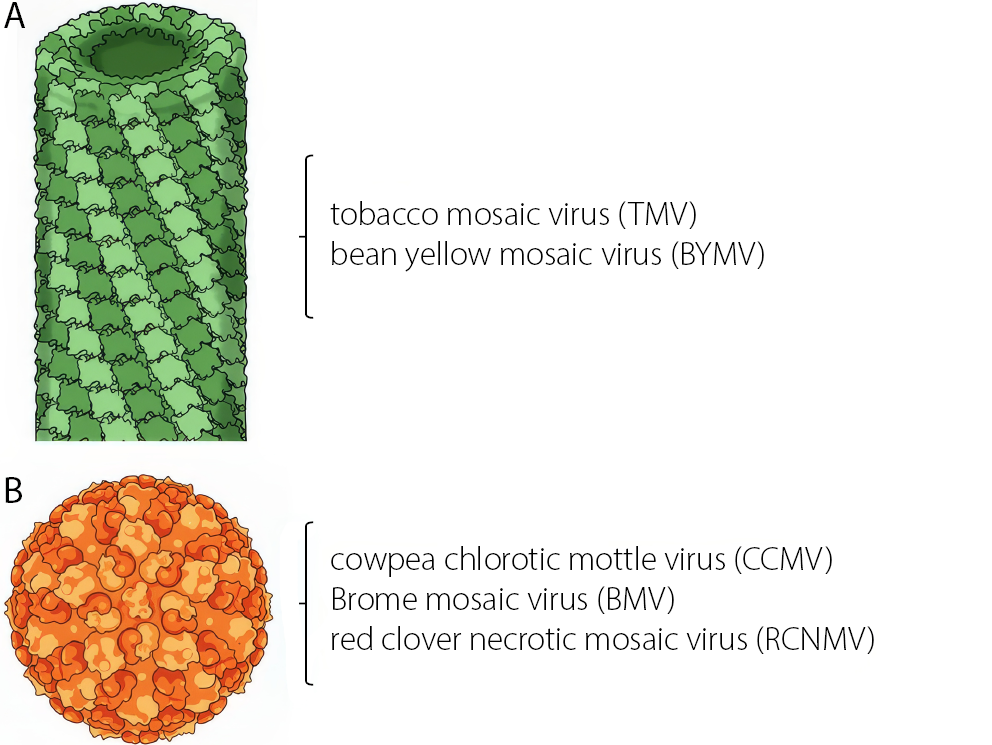

Currently, much of the research on VLPs focuses on obtaining capsids from plant pathogenic viruses, as their manipulation and inoculation are simpler than those of animal viruses and they do not pose biological risks. Plant viruses generally exhibit 2 main structural types: rod-like forms, such as the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), and icosahedral forms, such as the cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV) of the Bromovirus genus – both of which are widely used as nanocarriers (Figure 2). Regardless of their structure, viruses possess functional groups on their surfaces that can be used to anchor molecules such as antibodies or peptides, thereby improving targeting and enhancing therapeutic efficacy.59,60,62,63

Plant virus-like particle platforms for drug delivery emerged in the early 21st century, with several key studies demonstrating the ability of these viruses to transport cargos other than their genetic material and, subsequently, to deliver poorly water-soluble chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin (Table 1).15,17,29,42,50,59,60,62,64–80 However, one of the main advantages of using plant viruses as nanocarriers resulted in relatively simple production, low resource demand, high yield of virus per gram of infected leaf, and rapid purification of these.3,18

These characteristics, combined with the ease of production, storage and manipulation of this type of virus, are rarely found in other types of infectious viruses for humans, giving pVLPs an almost unbeatable advantage as biomaterials.

Encapsulation techniques

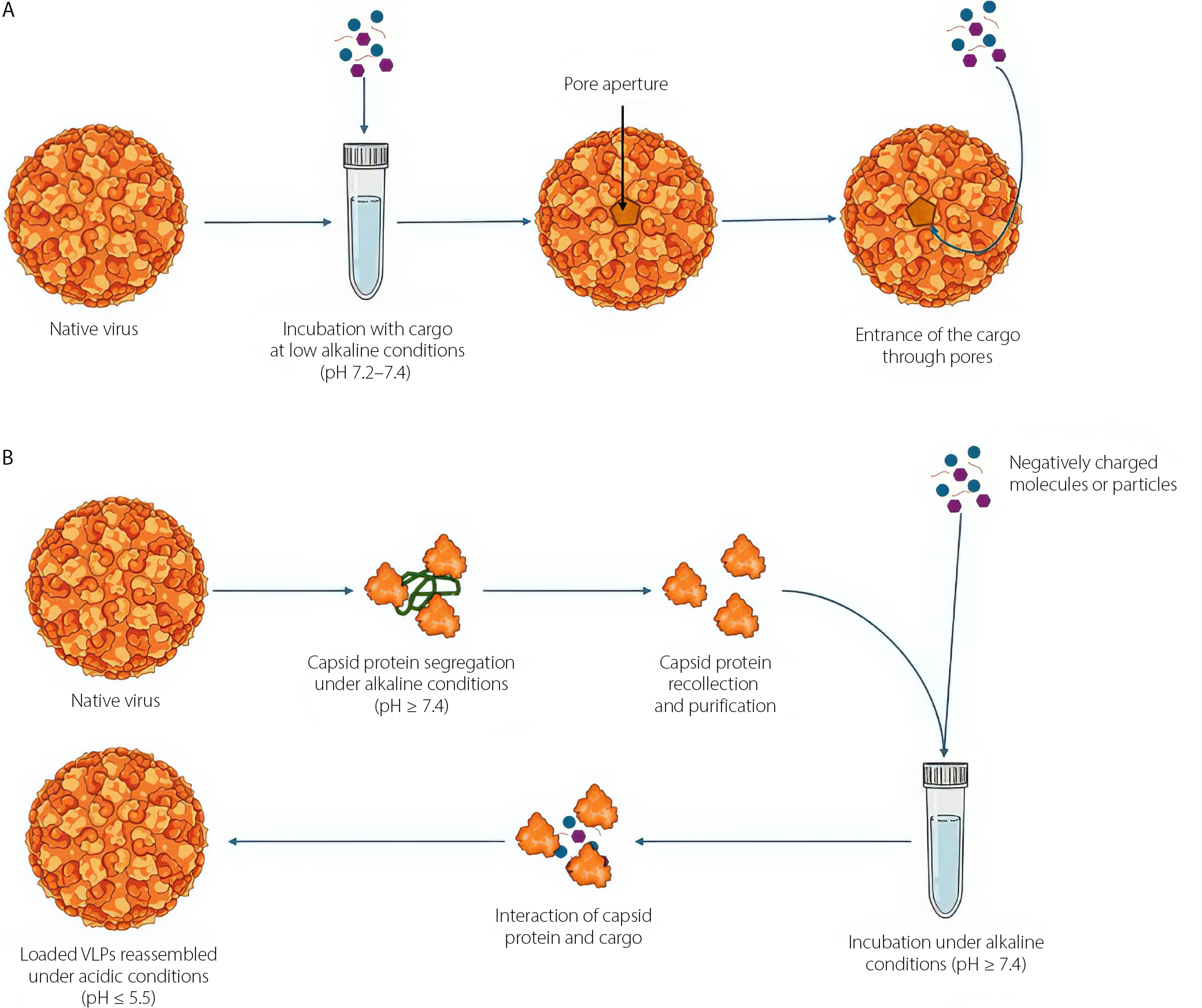

There are 2 main methods for loading the internal cavity of a VLP with cargo: reassembly of the CP around a negatively charged core, or infusion through pore opening. To induce pore expansion, the native virus and the cargo are incubated together under mildly alkaline conditions.42,59,65,81 Under acidic conditions, VLPs maintain their native conformation, whereas under alkaline pH conditions, their pores open, allowing the entry of cargo molecules in contact with them (Figure 3).82–84 However, it should be clarified that this method is limited by the pore size of the virus, so larger particles than that size will not be able to enter the internal cavity of the virus; for those purposes, encapsulation protocols through CP self-assembly are suggested. The self-assembly capability of viruses was first explored in 1955 through successful reconstruction of TMV in vitro.85 By the end of the 1960s, the assembly mechanisms of TMV were well known,86,87 and during the following decade, the self-assembly mechanisms of icosahedral plant viruses were studied and described.63 The reconstruction of the particles is first achieved by purifying the CP, generally subjecting the viruses to high ionic strength conditions, resulting in the disassembly of the virions into proteins and nucleic acids. At that point, the proteins are recovered and the nucleic acids are removed. The protein must be purified before attempting to assemble the cargo. To achieve assembly, the CP is incubated in cycles with the cargo under high ionic strength conditions, followed by incubation or dialysis against an acidic pH buffer solution (Figure 3). These changes in electrostatic forces promote the binding of positively charged amino residues inside the capsid to the core, which must have a negative electrostatic charge.53,60,64,66 Since then, this field of research has developed significantly.

Recently, a strategy based in the infusion using metal ions and pH-dependent reversible mechanisms has been developed.65,67 This approach relies on the opening of capsid pores induced by abrupt pH changes: At acidic values, the particles retain their native conformation, whereas under basic conditions, the pores open and permit the incorporation of molecules of interest.

Structural modifications

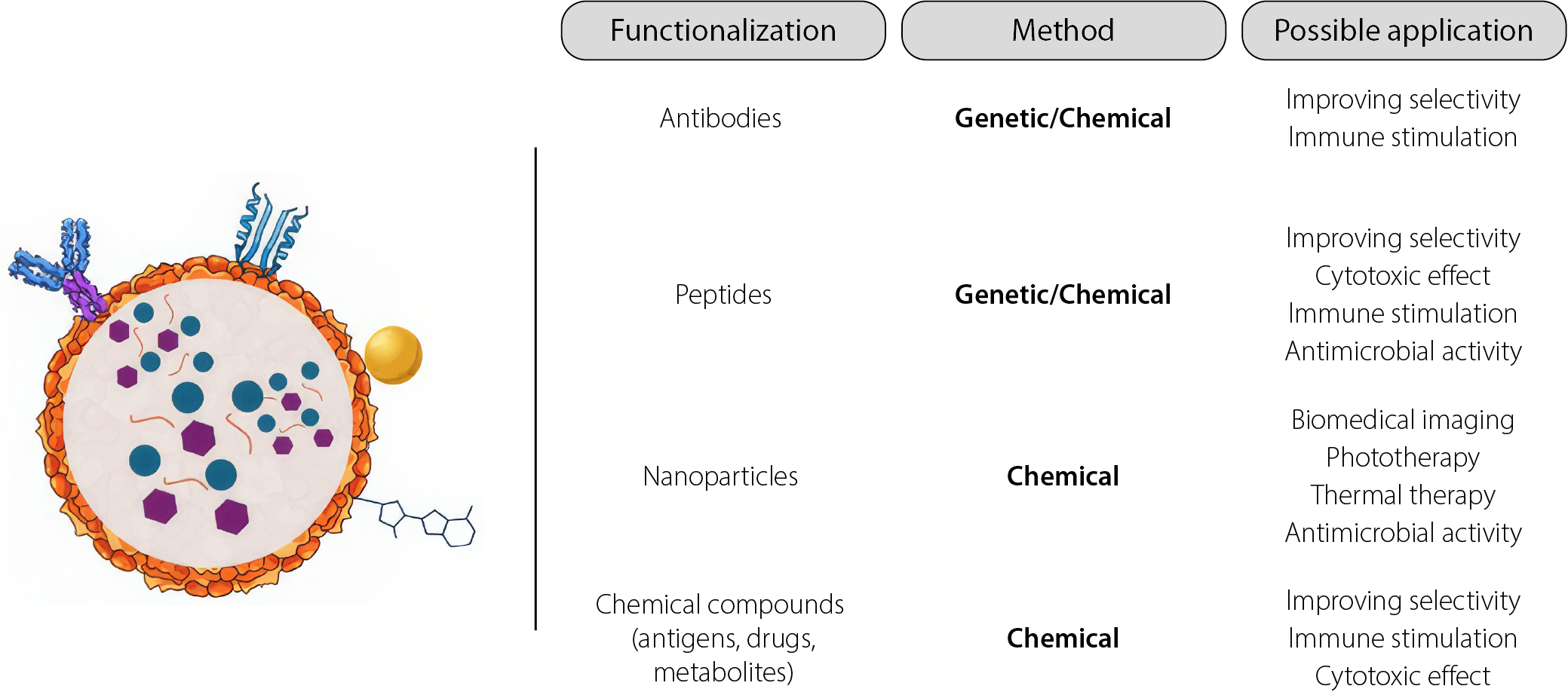

Almost half of the virus families have icosahedral geometry, with CPs that facilitate assembly and disassembly to introduce the cargo. The proteins that form the surface, called “coat proteins”, contain lysine, cysteine and aspartic/glutamic acid residues that can be modified or used as an anchoring platform for other molecules. The main types of functionalization are based on the conjugation of biomolecules (bioconjugation) such as antibodies, peptides, oligonucleotides, or carbohydrates68–72; however, fuctionalization can be also achieved with organic and inorganic molecules, such as drugs (Figure 4), various chemical agents, such as N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), polyethylene glycol (PEG), biotin, or carbodiimide, as well as through genetic modification methods.71,73,74

The first approach of the conjugation of a VLPs was made by Frank et al. in 1971; They conjugated a decapeptide representing a fraction of the TMV CP to a succinylated bovine serum albumin and observed an immunization effect in rabbits. Years before, Kriwaczek et al. conjugated molecules of α-melanotropin to TMV virus like particles, creating the first conjugated plant VLP.75,76 First spherical fitovirus to be functionalized was the CCMV, by Wang et al.3,88 Hydrazone conjugation is a relatively recent chemoselective strategy that enables the sequential and controlled introduction of multiple peptides by regulating the reaction conditions. This technique demonstrates high chemoselectivity, with the resulting products exhibiting absorbance around 350 nm. The method is based on the reaction between a terminal hydrazine group on the substrate and benzaldehyde-functionalized VLPs. Hydrazone chemistry is particularly valuable for conjugating VLPs with ligands that are unstable under click chemistry conditions.10,77,78

Biomedical applications

The use of VLPs has considerably expanded across the spectrum of biological and medical sciences, having outstanding applications for both areas. With VLPs, it is possible to perform gene therapy, diagnostic utility testing, targeted delivery systems, and vaccine development.2,5,6,89–91 These applications have supported the development of therapeutic strategies for the treatment of cancer, neuropathological disorders and other diseases of genetic origin.

Targeted delivery

The proper administration of therapeutic drugs has 2 challenges: correct dose delivery and the reduction of side effects through targeted delivery.27,48,92 The ideal drug dose is determined by balancing bioavailability and concentration to achieve therapeutic efficacy. However, this balance is often disrupted by physiological processes that degrade the active compound before it reaches its target site. To compensate, drug concentrations are frequently increased, which can lead to adverse side effects resulting from excessive exposure of healthy tissues to the drug.93–95 As other NPs, the application of VLPs ensures the integrity of the dose until it is delivered specifically. It is achieved through bioconjugation techniques, but in contrast with other NPs, the VLPs and pVLPs exhibit chemical groups allowing to be conjugated with molecules of different natures that respond to indicated situations without previous modifications; e.g., in conjugation with antibodies, the particle recognizes a receptor on the cell and triggers a response. Other molecules such as peptides, carbohydrates and nucleic acids are also used to direct therapy to specific cells and they can be anchored directly to the VLP or pVLP on the surface.6,96 Meanwhile, other classes of NPs, such as metallic NPs or mesoporous silica NPs, require the addition of chemical groups to which other molecules can be anchored through chemical modifications performed either during or after synthesis. Similarly, various mechanisms employ strategies that exploit disease-specific conditions – e.g., the acidic environment of the tumor microenvironment (TME), where pH changes are utilized to trigger the release of chemotherapeutic agents.97–99 Other NPs have exhibited toxic effects and failed to induce the desired pro-inflammatory response. These side effects are associated with factors such as surface charge and size polydispersity of the NPs.100 Monodispersity has been identified as an important characteristic for efficient cellular uptake.101 Through evolutionary processes, viruses achieved monodisperse size – a feature that can be exploited to minimize unwanted activation of the inflammatory response. Consequently, VLPs and pVLPs can function as targeted delivery systems that help reduce undesirable toxic or proinflammatory effects.3,18,102

Immunomodulation

The immunomodulatory activity of VLPs is related to the mimicry they can have with wild viruses. Like a wild virus, VLPs are capable of activating the immune response at the humoral or innate level. The size and structure of VLPs alert antigen-presenting dendritic cells, which will subsequently initiate the action chain of the adaptive response, but they can also be recognized by toll-like receptors (TLR) of the innate system.103 Some clinical studies have used viral particles from pathogenic viruses such as influenza and have reported the induction of an effective immune response (both humoral and cellular), which has allowed the development of vaccines, findings in immunotherapy and the fight against immunodeficiency.103–105 Through recombinant DNA and genetic engineering methods, chimeric VLPs can be synthesized that express short sequences of peptides or proteins, which allows for the maintenance of peptide integrity and achieving optimal therapeutic activity.68,79 This strategy has been used both for vaccine development and recruitment of immune system cells in tumors.

Vaccine production

There is a wide variety of approved vaccines based on VLPs, and many more are in development or clinical trial phases. Some of the VLP-based vaccines on the market include CervarixVR (HPV), Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Merck and Co., Inc.’s Recombivax HBVR.106 The immune response to these vaccines focuses on the recombination of the particle with specific antigens that generate immunity, the delivery of RNA transcripts that will be translated to produce the immunogenic response, or the delivery of specific antigens.56,107,108 The transport of specific epitopes in VLPs for vaccines has demonstrated the ability to generate memory in immunity, leaving the immune system prepared for an infection event, in addition to being able to fully transport the epitopes.7,58 Complementarily, VLPs offer a solid and well-designed alternative platform for the development of cancer vaccines. Various working groups have created cancer vaccines using VLPs for different types of cancer.51,52,99 In addition to strategies that display epitopes on the surface of the VLP, other strategies use VLPs to transport mRNA transcripts to induce immunity against certain types of cancer.58 Vaccines based on pVLPs began to be developed in the previous century. The first pVLP vaccine candidates were generated using TMV as a platform.15,76 Plant viruses such as TMV and CCMV have shown promising characteristics for vaccine development, including biocompatibility, efficient and selective immune activation, and well-described genetic and phenotypic profiles that make them highly amenable to modification. Additionally, the production costs of these vaccine platforms are comparatively low. Despite having great utility and good results in this field, the greatest benefit that VLPs provide to vaccine development is the broad potential for improvement they present.

Discussion

Historically, viruses have been regarded as agents of disease and epidemics, a perception that has long shaped the public consciousness. However, with the technological and scientific advances of the contemporary era, it is now recognized that viruses can also function as bio-nanoparticles (bio-NPs) with a wide range of biotechnological and medical applications (Figure 5).

The self-assembly capability allows for effective encapsulation of therapeutic and theranostic molecules, such as antigens, fluorescent markers, metals, and drugs, facilitating targeted delivery to tissues or organs.66,95,98,109 Given their capacities, CP proteins can be used, designed and modified to produce natural, safe, stable and biodegradable nanocages for therapeutic purposes.

On the other hand, VLPs have also positioned themselves in the fields of vaccine generation. Compared to traditional vaccines, which are often produced from an attenuated or inactivated viral strain, genome-free VLPs allow for the transport of RNA transcripts or isolated antigens that enable the activation of the immune response, offering innovative alternatives that are safe.7,72,106,107 The variety of VLPs makes them structurally attractive and functionally diverse, allowing them to be designed to carry antigenic molecules to specific target tissues. Nevertheless, most of commercial VLP based vaccines use mammalian viruses as platform.106 Consequently, the production methods, storage and transportation requires more resources, and bioethical considerations that significantly influence the costs and availability of these vaccines. In contrast, plant viruses can be easily propagated, facilitating the large-scale production of p-VLPs and potentially reducing costs. Furthermore, viruses such as TMV and its mutants exhibit significant temperature resistance,110,111 eliminating the need for preserving a cold chain.

Although the development of VLPs is relatively recent, it has been demonstrated that they have enormous potential to resolve therapeutic problems.3,6,49

Limitations

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of key works that have contributed to the development of pVLPs for biomedical applications, from their initial conceptualization in the past century till now. It is important to emphasize that although some of the studies discussed here describe the physicochemical properties of pVLPs and fundamental proof-of-concept experiments (e.g., CP reassembly and NP encapsidation), the primary focus was on those that demonstrated biotherapeutic applications or represented pioneering exploratory efforts that have driven the advancement of pVLPs in biomedical research.

Conclusions

This work has explored the development of pVLPs as nanocarriers in the emerging era of nanomedicine, encompassing their use in the delivery of novel therapeutic agents, antigen presentation, and the enhancement of existing drugs through improved bioavailability, solubility and stability.

The comprehensive compilation of the most relevant findings and historical studies is important for understanding the development of pVLPs, as well as recent advances that demonstrate their current applications, relevance and future potential. Furthermore, this review highlights the inherent advantages of pVLP production methods and the mechanisms by which drug loading is achieved, providing an overview of their therapeutic promise.

Finally, new technologies and methodologies may further enhance pVLP production, loading strategies and biomedical applications. Future studies should also focus on evaluating key characteristics such as structural integrity, safety and potential toxicity during the preclinical stage.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.