Abstract

• Cocoa pod gum (CPG) offers a biodegradable and sustainable alternative to synthetic binders in pharmaceutical tablets.

• CPG-based metronidazole tablets show faster disintegration and drug release, ideal for immediate release formulations.

• Compared to xanthan gum, CPG demonstrates superior flow properties and swelling capacity with no drug incompatibility.

• CPG is a cost-effective, eco-friendly binder with physicochemical properties suitable for tablet formulation.

Background. Natural gums offer environmentally friendly, biodegradable and non-toxic alternatives to synthetic binders in pharmaceutical formulations. Cocoa pod gum (CPG), derived from cocoa pod husk (CPH), presents a sustainable and underexplored source for pharmaceutical application.

Objectives. This study investigates the potential of CPG as a natural binder in metronidazole tablet formulations, evaluating its physicochemical and compressional properties, mechanical strength, drug release behavior, and compatibility with the active pharmaceutical ingredient.

Materials and methods. The CPG was extracted from CPH and characterized alongside xanthan gum (XNG), a standard natural binder. Physicochemical analyses included pH, flow properties, viscosity, particle size, crystallinity, and thermal behavior. Compaction behavior was assessed using Heckel and Kawakita equations. Metronidazole tablets were formulated with varying concentrations (10–20% w/w) of both gums and evaluated for hardness, friability, disintegration time, and in vitro drug release. Compatibility was examined using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR).

Results. Cocoa pod gum demonstrated better flow properties and swelling capacity, while XNG showed higher viscosity and plastic deformation, yield pressure (Py) and PK values. Tablets formulated with XNG had greater hardness and slower disintegration, resulting in more delayed drug release. Cocoa pod gum-based tablets disintegrated faster and showed rapid drug release, making them more suitable for immediate release formulations. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy confirmed no drug-excipient incompatibilities.

Conclusions. Cocoa pod gum exhibits promising binder properties comparable to XNG and may serve as a cost-effective, sustainable and biocompatible alternative to conventional excipients in tablet formulations.

Key words: drug release, cocoa pod gum, natural binder, tablet formulation, compaction behavior

Background

Natural gums and mucilages are biopolymers that provide eco-friendly, biocompatible, biodegradable, and cost-effective alternatives to synthetic excipients in pharmaceutical formulations.1, 2, 3 These plant-derived polymers serve multiple functional roles – including binders, disintegrants, stabilizers, and release modifiers – across various dosage forms.1,4

Unlike synthetic polymers, which may have challenges regarding toxicity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and environmental concerns, natural gums are non-toxic and non-irritant, making them ideal for sustainable drug delivery systems.2, 4 The polysaccharide structures of natural gums allow for chemical modifications to enhance their performance in modified drug delivery systems applications.5, 6, 7

Agricultural by-products are increasingly explored as sustainable sources of functional polymers.8, 9, 10 The large quantities of agro-industrial waste generated worldwide contribute substantially to environmental pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.11 Valorizing such waste through its conversion into useful bioproducts not only mitigates environmental impacts but also enhances its economic value.

Cocoa pod husk (CPH), a major by-product of Theobroma cacao, is rich in polysaccharides and represents a promising raw material for gum extraction.12, 13 Cocoa pod gum (CPG), derived from CPH, has demonstrated potential as a binder in tablet formulations, offering an innovative and sustainable approach to excipient development.14 Metronidazole is a widely used nitroimidazole antimicrobial that is effective against anaerobic bacteria and protozoa. It is commonly formulated in tablet dosage forms, where the binder plays a crucial role in ensuring adequate mechanical strength, disintegration, and dissolution efficiency.

Objectives

Traditional binders such as starch and synthetic polymers have long been used in tablet formulations; however, they may pose challenges related to cost, potential toxicity and limited sustainability.4 Consequently, the search for novel, plant-based binders has become increasingly important. Cocoa pod gum represents a promising alternative, offering a sustainable, eco-friendly and cost-effective option compared with conventional synthetic polymers. The present study explores the applicability of CPG as a binding agent in metronidazole tablet formulations. The study aims to evaluate the compressional behavior, mechanical properties, drug release profile, and compatibility of CPG with metronidazole, using xanthan gum (XNG) as a standard binder for comparison.

Materials and methods

The materials used in this study included metronidazole (a gift from Exus Pharmaceuticals, Ejirin, Nigeria), xanthan gum (Jungbunzlauer, Germany), lactose monohydrate (Ind-Swift Labs Ltd., Parwanoo, India), corn starch (S.D. Fine Chemicals, Mumbai, India), magnesium stearate (Loba Chemie Ltd., Mumbai, India), and CPH (locally sourced). All other solvents and reagents used were of analytical grade.

Collection and extraction of cocoa pod gum from Theobroma cacao

Dried CPHs were locally sourced in Ago-Iwoye, Nigeria. The husks were sun-dried for approx. 2 weeks, ground into a fine powder, sieved and further dried in a hot-air oven. Briefly, 500 g of CPH powder were subjected to aqueous extraction by boiling in 3 L of distilled water at 80°C for 2 h with continuous stirring. The resulting mixture was filtered through white muslin cloth, and the filtrate was treated with acetone in a 3 : 1 (v/v) ratio to precipitate the gum. The precipitate was collected by filtration and dried in a desiccator. The dried product, referred to as CPG, was then ground and passed through a fine sieve.

Phytochemical screening

Cocoa pod husk and the CPG were subjected to phytochemical screening using well-established procedures to detect the major classes of secondary metabolites.14 The frothing test was used for the detection of saponins, while Molisch’s test confirmed the presence of carbohydrates. Alkaloids were identified using Mayer’s, Dragendorff’s and Wagner’s reagents. Proteins were detected by the Biuret and Ninhydrin tests. Additional phytochemical constituents screened included lignin, tannins, flavonoids, and triterpenoids.

Physicochemical properties

pH determination

A dispersion of each gum was prepared by dissolving 1 g of CPG or XNG in 50 mL of distilled water and allowed to stand. The supernatant pH was then measured with a Jenway pH meter model 3510 (Jenway, Great Dunmow, UK). Each measurement was performed 3 times, and the mean value was calculated.

Density and flow properties determination

The bulk density, tapped density and true density of both gums were determined using standard procedures as described by Adeleye et al.14 Flow properties – including the angle of repose, Hausner’s ratio and Carr’s index – were also evaluated following the methods outlined in the same reference.14

Mean particle size distribution determination

The mean particle size distribution of each gum was determined by sieving 20 g of sample through a series of sieves arranged in descending mesh sizes (1.0 mm to 90 µm). The sieve stack was mounted on a mechanical shaker (Endecotts, London, UK) and operated for 15 min at room temperature to facilitate particle separation according to size. The material retained on each sieve was weighed, the percentage retained was calculated, and these values were used to compute the mean particle size for each gum.15

Moisture content

The loss on drying method was employed to determine the moisture content. A 5 g portion of gum was weighed and placed into a pre-tarred glass petri dish and dried in an oven at 105°C to constant weight. The percentage of moisture loss was calculated by subtracting the weight after drying from the initial weight, divided by the weight after drying and multiplying by 100.

Swelling capacity

Three grams each of gum were transferred into separate 50 mL measuring cylinders, followed by the addition of 20 mL of distilled water. The cylinder was agitated at 10-min intervals for 1 h at room temperature, then it was left undisturbed at room temperature for 5 h. Swelling capacity (%) was calculated as the difference between the hydrated and initial tapped volumes of the gum, divided by the initial tapped volume and multiplied by 100.

Viscosity of gum

The viscosity of each gum was determined using 2% w/v aqueous dispersions, which were allowed to hydrate for 2 h before measurement. Viscosity was measured at room temperature using a Brookfield DV-II+ Pro viscometer (AMETEK Brookfield, Middleboro, USA) fitted with spindle No. 2, operating at a shear rate of 50 rpm.

Physicochemical characterizations of the gums

The physicochemical characteristics of the gums were evaluated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), following the procedures described by Adeleye et al.14 Scanning electron microscopy was employed to examine the shape and surface morphology of the gums. A focused electron beam was directed onto the sample surface to obtain high-resolution images at various magnifications. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy was performed using an FTIR spectrophotometer, with the samples prepared as potassium bromide (KBr) pellets. The crystallinity of the gum samples was determined using XRD to evaluate their amorphous or crystalline nature. The thermal behavior of the gums was analyzed using DSC, which measures differences in heat flow associated with physical and chemical transitions within

the samples.

Preparation of gum compacts

Tablet compression was carried out using a Carver hydraulic manual hand press (Model C; Carver Inc., Menomonee Falls, USA). Briefly, 500 mg portions of CPG and XNG powders were individually compressed into tablets using a 10 mm diameter die fitted with flat-faced punches. A 1% w/v solution of magnesium stearate in ethanol was applied to the die surfaces as a lubricant prior to compression.

Tablets were compressed at 6 different pressure values – 28.82, 56.64, 84.96, 113.28, 141.60, and 169.92 MPa – with a dwell time of 30 s. After ejection, the tablets were stored over silica gel for 24 h to allow for elastic recovery. Tablet weight, thickness and diameter were then measured using standard procedures.

Compaction properties

Heckel plot

The Heckel equation, proposed by Heckel,16is commonly used to study the compaction behavior of powders. It relates the relative density of a powder bed (D) to the applied compression pressure (P).

The Heckel equation is expressed as:

where: D – relative density of the compact at pressure P, K – slope of the linear portion of the plot and A – intercept of the extrapolated linear region. The reciprocal slope K = mean yield pressure (Py) of the material. The intercept A is related to the original compact volume and reflects 2 stages of consolidation – densification due to the initial relative density of the powder and densification by particle rearrangement before deformation.

The relative density of powder bed at the onset of plastic deformation (DA) is calculated using

The relative density (D0) – the density at zero pressure – describes the initial rearrangement phase of densification immediately after die filling, before compression. While the relative density of powder at low pressure (DB) describes the extent of particle rearrangement at low pressures during initial stages of compression before plastic deformation is defined as

Kawakita equation

The Kawakita equation describes the relationship between the volume reduction of a powder bed and the applied pressure during compression.17 It is expressed as follows:

The equation can be simplified to yield:

where: C – degree of volume reduction, V0 – initial volume of the powder bed, VP – volume under applied pressure P, and a and b are constants characteristic of the powder material. A plot of P/C vs P is used to obtain the constants a and b. Constant “a” is the minimum porosity before pressure is applied, while the reciprocal of the constant “b” is designated as PK, which represents the pressure required to reduce the powder bed volume by 50%.

Determination of mechanical properties of compact

Tablet hardness test

Tablet hardness was determined using a Monsanto hardness tester (Campbell Electronics, Mumbai, India). Each tablet was placed between the spindle and the anvil of the tester, and the knob was gently turned until the tablet was held firmly in position. The pointer was then set to 0, and pressure was gradually applied until the tablet fractured diametrically. The pressure at the point of fracture was recorded as the hardness value. This procedure was repeated 3 times for each tablet batch.

Tablet friability test

Tablet friability was determined using a Veego tablet friability apparatus (Veego Scientific Devices, Mumbai, India). Ten tablets were collectively weighed (W₁) and placed in the friabilator, which was operated at 25 rpm for 4 min. The tablets were then removed, dedusted and reweighed (W₂). The percentage friability was calculated using the following equation:

This determination was carried out in triplicate, and the mean value was recorded..

Formulation of metronidazole tablet

Briefly, 200 mg of metronidazole powder was blended with 5 different concentrations (10.0% w/w, 12.5% w/w, 15.0% w/w, 17.5% w/w, and 20.0% w/w) of CPG and XNG, respectively, to yield a total of 10 formulations, as presented in Table 1. Each formulation also contained 50 mg of corn starch as a disintegrant, and the total tablet weight was adjusted to 100% using lactose monohydrate as a filler. The powder blend was mixed in a planetary mixer for 5 min. Then, 400 mg of the blend from each formulation batch was directly compressed using a Carver hydraulic manual hand press (Model 38510E; Carver Inc.) fitted with flat-faced 10 mm diameter punches. A 1% w/v solution of magnesium stearate in ethanol was applied to the die surfaces as a lubricant prior to compression. Tablets were compressed at a pressure of 113.28 MPa with a dwell time of 30 s.

Metronidazole tablet evaluation

Tablet hardness and friability were determined following the procedure used for evaluating the mechanical properties of compacts.

Assessment of disintegration time

of metronidazole tablet

The disintegration test was performed using a DBK tablet disintegration apparatus (DBK Instruments, Mumbai, India), with distilled water maintained at 37 ±0.5°C as the disintegration medium. The time required for each tablet to completely disintegrate and pass through the mesh was recorded. All measurements were carried out in triplicate, and the mean disintegration time was calculated.

Calibration curve of metronidazole

A calibration curve for metronidazole was constructed by preparing standard solutions in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid (HCl) at concentrations ranging from 1 to 6 µg/mL. The absorbance of each solution was measured at 278 nm using a Jenway UV-7305 UV–Visible spectrophotometer (Jenway), and the resulting data were used to generate a linear equation.

Dissolution profile of metronidazole tablet

Drug release was evaluated using a USP rotating basket dissolution apparatus (Biobase Model BK-RC1; Biobase Biodustry Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) operated at 50 rpm in 900 mL of 0.1 N hydrochloric acid (HCl) as the dissolution medium, maintained at 37 ±0.5°C. At predetermined time intervals, 5 mL samples were withdrawn and immediately replaced with an equal volume of fresh dissolution medium. The withdrawn samples were analyzed spectrophotometrically at 278 nm using a Jenway UV-7305 UV–Visible spectrophotometer (Jenway). All tests were performed in triplicate, and the mean values ± standard deviation (SD) were recorded. The percentage of drug released at each time point was calculated from the calibration curve (Figure 1).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) and GraphPad Prism v. 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). Results are expressed as mean ± SD from at least 3 replicates for each analysis. Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed to evaluate significant differences among the tablet formulations. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all cases.

Results

Physicochemical properties the gums

The physicochemical properties of CPG and XNG, including color, odor, particle size, true and bulk densities, and flow indices (Hausner’s ratio, Carr’s index, and angle of repose), are summarized in Table 2. Additional parameters evaluated included swelling capacity, moisture content, viscosity, pH, and crystallinity index to assess their suitability for tablet formulation.

Cocoa pod gum appeared as a dark brown powder with a characteristic coffee-like odor, whereas XNG was white and odorless. The mean particle diameter of CPG (118.61 μm) was larger than that of XNG (83.08 μm). Regarding densities, the true density of XNG (1.352 g/cm³) was higher than that of CPG (1.198 g/cm³). The bulk and tapped densities of both gums were relatively similar; however, XNG exhibited a slightly higher tapped density (0.769 g/cm³) compared with CPG (0.690 g/cm³).

Regarding flow properties, XNG exhibited a higher Hausner’s ratio (1.44) and compressibility index (30.66%) compared with CPG, which showed a Hausner’s ratio of 1.30 and a compressibility index of 23.20%. The angle of repose was significantly higher for XNG (23.96°) than for CPG (20.53°) (p < 0.001), indicating poorer flowability of XNG. In contrast, CPG exhibited a significantly higher moisture content (18.20%) compared with XNG (11.20%) (p < 0.001).

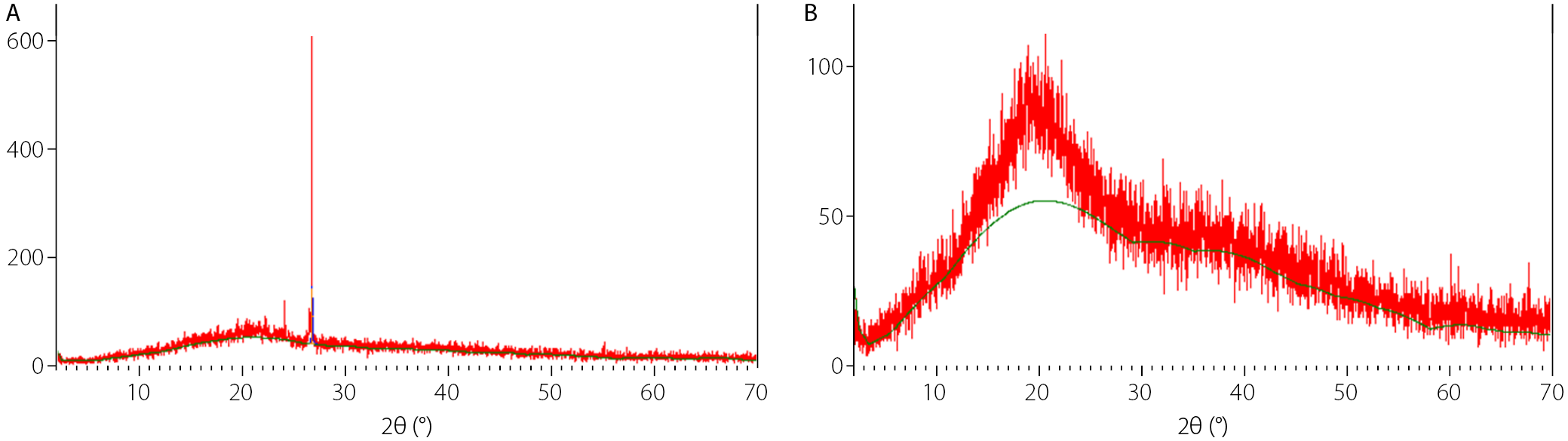

A similar trend was observed for swelling capacity, where CPG demonstrated a significantly greater swelling capacity (60.45%) compared with XNG (51.53%) (p < 0.001). The pH values of both gums were near neutral, with CPG exhibiting a pH of 7.2 and XNG a pH of 6.8, indicating good compatibility for oral formulations. Interestingly, CPG showed a markedly higher crystallinity index (84.14%) than XNG (44.74%).

Phytochemical properties of the gums

The phytochemical constituents of CPH and CPG were evaluated, and the results are presented in Table 3. The CPH extract contained a wide range of phytochemicals, including saponins, tannins, alkaloids, carbohydrates, flavonoids, proteins, lignin, and triterpenoids, whereas these constituents were absent in the purified gum (CPG).

Compressional properties of the gums

The compressional behavior of CPG and XNG was evaluated using the Heckel and Kawakita equations, and the results are presented in Table 4. The Heckel model describes the relationship between applied compression pressure and powder bed porosity, providing parameters such as the mean yield pressure (Pγ) and initial relative density (D₀). Xanthan gum exhibited a lower Pγ value (74.41 MPa) compared with CPG (138.52 MPa), indicating that XNG deforms more readily under pressure. In contrast, CPG showed a higher D₀ (0.445) than XNG (0.394).

The Kawakita model, which assesses volume reduction under pressure, provided values for total compressibility (a) and PK (pressure to reduce volume by 50%). Xanthan gum demonstrated a higher Di (0.420) than CPG (0.388), with a lower PK value (6.57) compared to CPG (7.88).

Mechanical properties of compacts

The results of hardness and percentage friability of tablets compressed at varying pressures (28.82–169.92 MPa) are presented in Table 5. Both gums exhibited increased hardness and reduced friability with increasing compression pressure. However, XNG produced tablets with significantly higher hardness and lower friability than those formulated with CPG at all pressure levels (p < 0.001).

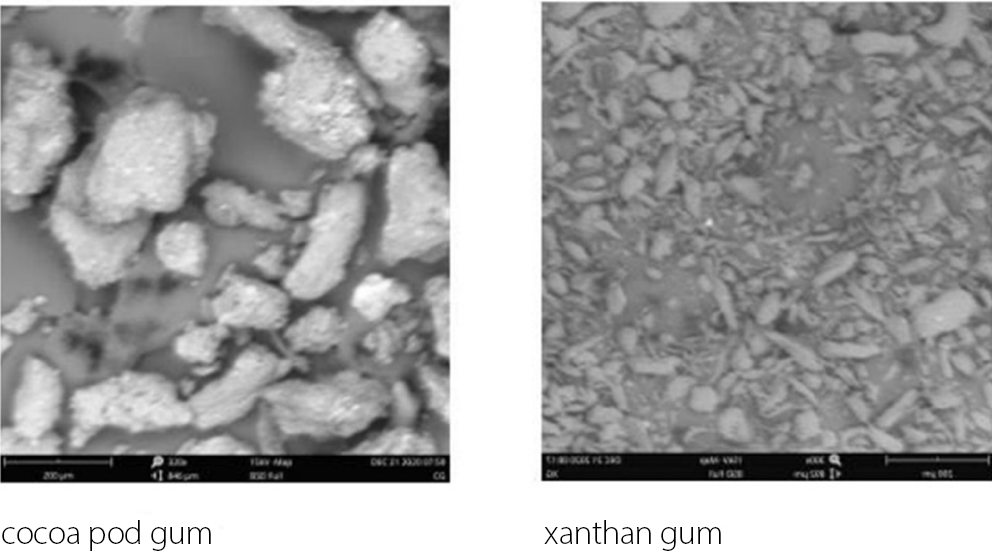

SEM analysis of the gums

The scanning electron micrographs of CPG and XNG are shown in Figure 2. The surface morphology of CPG displayed irregular, coarse and aggregated particles with rough surfaces and non-uniform edges, whereas XNG exhibited a finer and more fibrous morphology characterized by fragmented and elongated particles.

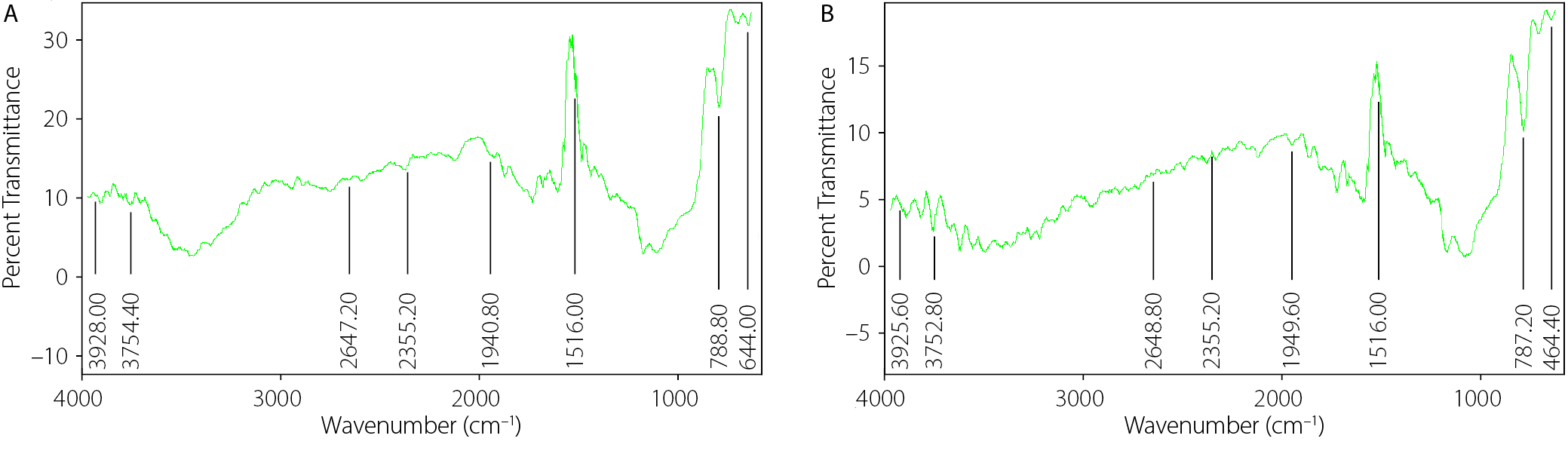

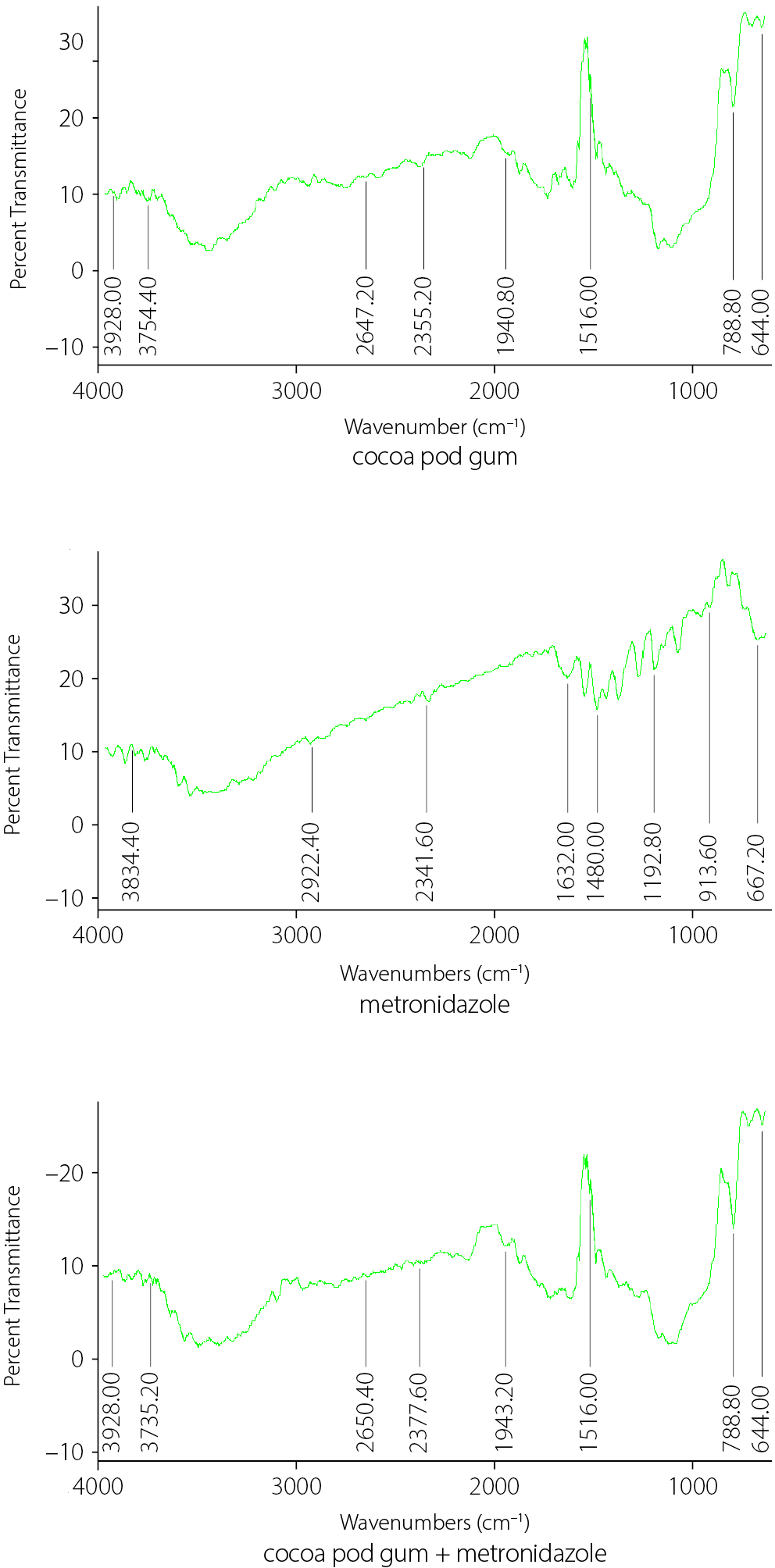

FTIR spectroscopy of the gums

The FTIR spectra of CPG and XNG are shown in Figure 3. Both gums exhibited characteristic absorption bands typical of polysaccharides, including a broad O–H stretching vibration in the region of 3,750–3,925 cm–1 and a distinct C–H or secondary O–H stretching band around 2,645–2,650 cm–1. No new peaks or significant peak shifts were observed in either spectrum. However, CPG displayed consistently higher peak intensities across all major absorption regions.

XRD analysis of the gums

The structural characteristics of CPG and XNG were further examined using XRD, and the resulting diffractograms are presented in Figure 4. The XRD patterns of both gums revealed distinct diffraction profiles, reflecting differences in their molecular organization and degree of crystallinity. Cocoa pod gum displayed a sharp and well-defined diffraction peak at 2θ ≈ 26.7°, indicating a higher level of crystallinity, whereas XNG showed a broad peak with maximum intensity in the 2θ region of 16–22°, characteristic of amorphous materials.

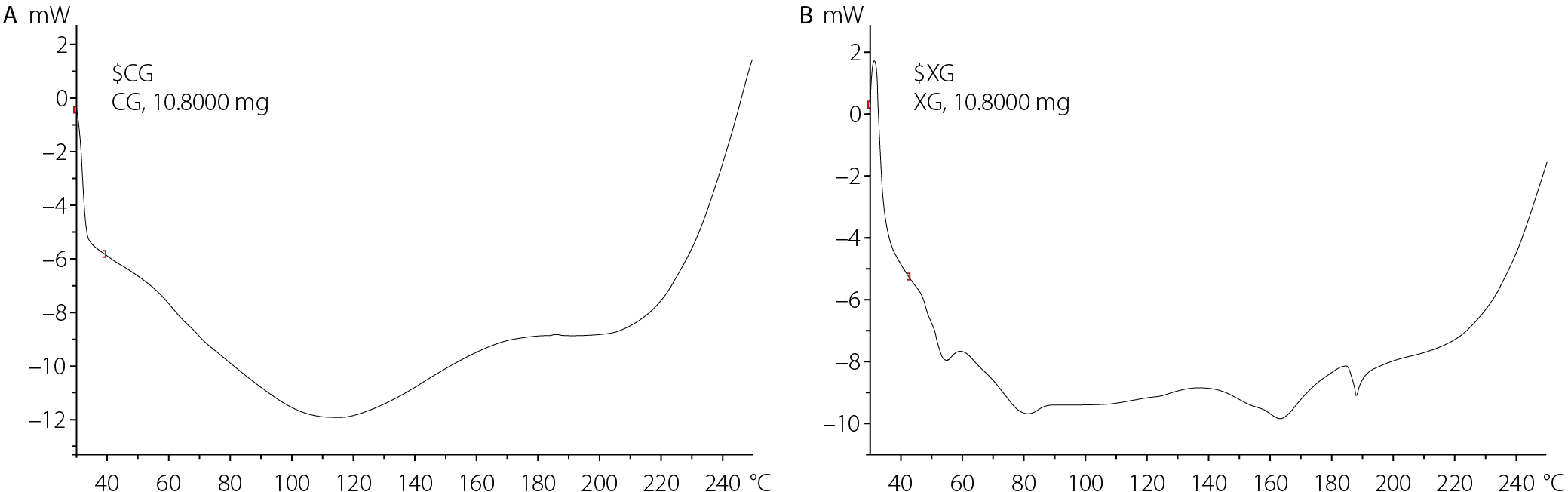

Thermal analysis of the gums

The thermal behavior of the isolated gums was analyzed using DSC to evaluate their thermal stability, and the resulting thermograms are presented in Figure 5. Cocoa pod gum exhibited a broad endothermic transition with an onset temperature of 30.16°C, a peak at 115.86°C, and an endset at 145.32°C. In contrast, XNG displayed a thermal transition beginning at 73.09°C, peaking at 81.00°C and ending at 243.65°C.

Compatibility studies

To ensure the safe and effective use of CPG as a binder in metronidazole tablet formulations, drug–excipient compatibility studies were performed using FTIR spectroscopy to evaluate potential interactions between metronidazole and CPG. The FTIR spectra of pure metronidazole, CPG and their physical mixture are presented in Figure 6.

Mechanical properties and disintegration time of metronidazole tablet formulations

The mechanical properties (hardness and friability) and disintegration times of metronidazole tablets formulated with CPG and XNG as binders are presented in Table 6. A statistically significant progressive increase in tablet hardness (p < 0.001) was observed with increasing binder concentration for both formulations. Tablet hardness ranged from 3.82 kgf (MCP1) to 6.05 kgf (MCP5) for the CPG-based tablets and from 5.08 kgf (MXN1) to 8.17 kgf (MXN5) for the XNG-based tablets. A corresponding decrease in friability was observed with increasing binder concentration, ranging from 2.32% to 0.81% for the CPG formulations (MCP1–MCP5) and from 1.09% to 0.35% for the XNG formulations (MXN1–MXN5). Tablets containing xanthan gum exhibited significantly lower friability (p < 0.003) compared with those containing CPG. Disintegration time increased with higher binder concentration, ranging from 4.54 min (MCP1) to 9.42 min (MCP5) for the CPG tablets, and from 6.81 min (MXN1) to 15.86 min (MXN5) for the XNG tablets. Xanthan gum-based tablets exhibited significantly longer disintegration times (p < 0.001) compared with CPG-based tablets at corresponding binder concentrations. However, all formulations generally complied with the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) disintegration limit of not more than 15 min, except for MXN5, which marginally exceeded this specification.

In vitro drug release profiles of metronidazole tablet formulations

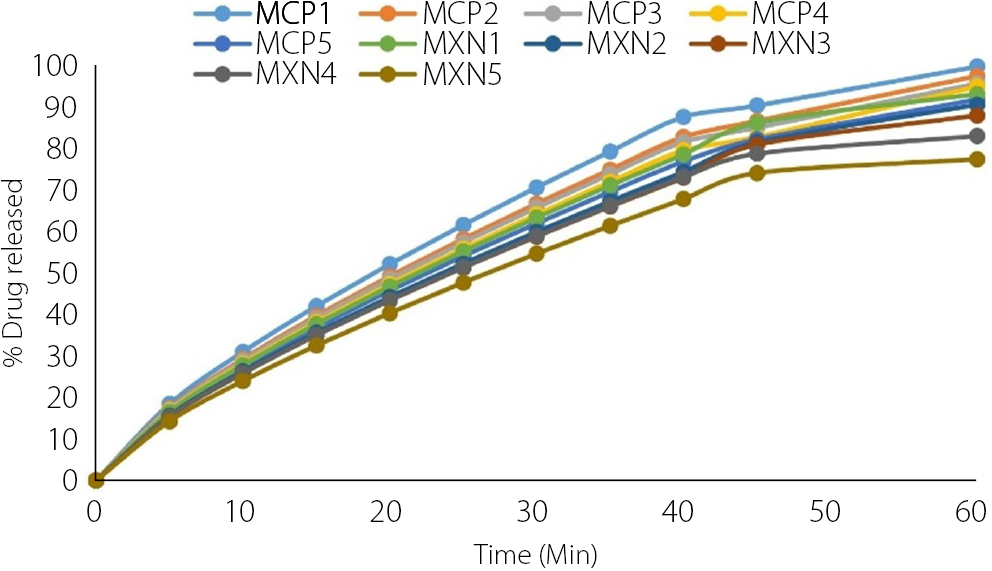

The in vitro release profiles of metronidazole tablet formulations containing CPG and XNG as binders are shown in Figure 7. Drug release was monitored over a 60-min period to evaluate the effect of binder type and concentration on the release profile. All formulations exhibited a time-dependent release pattern, with the percentage of drug released increasing progressively with time.

Cocoa pod gum formulations demonstrated faster drug release, achieving more than 85% release within 30 min across all batches and reaching up to 99.4% at 60 min. In contrast, XNG formulations exhibited a slower release profile, with cumulative drug release ranging from 79.1% to 92.8% at 60 min, and only the lower-concentration batches achieving ≥85% release within the first 30 min. Tablets formulated with lower binder concentrations exhibited faster drug release, whereas those containing higher binder levels showed a more sustained release profile. In general, CPG formulations complied with the USP dissolution requirement of not less than 85% drug release within 30 min. By contrast, formulations containing higher concentrations of XNG displayed a slower release profile, with partial deviation from the USP specification for immediate-release tablets.

Discussion

The physicochemical properties of CPG and XNG, as presented in Table 2, are essential for evaluating their suitability and acceptability as pharmaceutical excipients – particularly with respect to appearance, flow behavior, swelling capacity, viscosity, and structural integrity. The observed physicochemical characteristics of both gums indicate distinct differences that may influence their functional performance in pharmaceutical formulations.

Cocoa pod gum exhibited a darker color and a characteristic coffee-like odor, whereas XNG was white and odorless, reflecting differences in their botanical source and purity profiles. The mean particle size of CPG was larger than that of XNG, which may influence powder flow and compressibility. According to standard pharmacopeial classification, angle of repose values below 30° indicate good flow, values above 40° suggest irregular flow, and those exceeding 50° denote poor flow.

Similarly, a Carr’s index of 5–15% indicates excellent flow, 16–18% good, 19–25% fair, 26–35% poor, and values above 40% denote cohesive powders with very poor flow. Similarly, Hausner’s ratio values below 1.25 reflect good flow, whereas values above 1.25 indicate poor flow characteristics. The flowability indicators, including Carr’s index and Hausner’s ratio, suggested better flow for CPG compared with XNG, a trend further supported by the lower angle of repose observed for CPG.

Specifically, the angle of repose was significantly higher for XNG (23.96°) than for CPG (20.53°) (p < 0.001), although both values fall within the range indicative of good flow. However, XNG exhibited a higher Carr’s index (30.66%) and Hausner’s ratio (1.44), corresponding to poor flow, compared with CPG, which showed a Carr’s index of 23.20% (fair flow) and a Hausner’s ratio of 1.30 (poor flow). These differences may influence blend uniformity and tablet die filling during formulation. Xanthan gum exhibited markedly higher viscosity than CPG, suggesting superior gelling and thickening properties. The crystallinity index of XNG was lower than that of CPG, indicating its predominantly amorphous nature. This lower degree of crystallinity contributes to the higher viscosity of XNG, as previously reported by Yahoum et al.18and supported by additional findings.19 Phytochemical screening was conducted to determine the presence of bioactive compounds that may influence the functional and therapeutic properties of the materials. Cocoa pod husk contains a wide range of phytochemicals, whereas these constituents are absent in CPG, as presented in Table 3. This confirms that the purification process effectively removed the bioactive components, yielding a chemically inert polysaccharide matrix desirable for pharmaceutical use, as it enhances the biocompatibility, chemical stability and safety of the gum in drug formulations, minimizing the risk of drug–excipient interactions.

The compressional behavior of CPG and XNG as pharmaceutical excipients was evaluated using the Heckel and Kawakita equations, which provide insight into the mechanism of powder densification under applied pressure – an important factor that determines the tabletability and compaction ability of powders during direct compression. These models enable a comparative assessment of the compressibility and deformation characteristics of the gums, supporting their potential use as functional tablet binders or matrix-forming agents. The Py value obtained from the Heckel analysis was significantly lower for XNG than for CPG, indicating that XNG undergoes plastic deformation more readily under applied pressure. Similarly, the PK value obtained from the Kawakita analysis, which represents the pressure required to achieve a 50% volume reduction, was lower for XNG than for CPG. This further confirms that XNG exhibits greater plasticity and better packing ability, making it more favorable for direct compression processes. The mechanical strength of compacts prepared using both gums, as evaluated by crushing strength and friability, revealed significant differences in compaction behavior and binding efficiency across increasing compression pressures. Hardness provides a measure of the mechanical integrity of a tablet, while friability assesses its tendency to crumble under abrasion.20 For both gums, an increase in applied pressure led to a corresponding increase in hardness and a decrease in friability, demonstrating improved compact consolidation and mechanical resistance to abrasion.

However, XNG produced compacts with higher hardness at all pressure levels compared to CPG. This suggests that XNG exhibits greater plastic deformation and interparticle bonding,21 which aligns with its lower Py and PK values observed in the Heckel and Kawakita analyses. These findings are consistent with literature reports indicating that XNG imparts excellent mechanical strength to materials.22 The large, aggregated structures with rough surfaces and non-uniform edges observed in CPG suggest a limited surface area, which may contribute to slower hydration rates and prolonged swelling in aqueous environments. In contrast, the finer, more fibrous morphology of XNG, characterized by fragmented and elongated particles, indicates greater surface area exposure, potentially facilitating faster water uptake and more rapid hydration dynamics.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was used to identify and compare the functional groups present in CPG and XNG. The spectra provided insight into their compatibility and chemical composition. Both gums exhibited characteristic polysaccharide functional groups typically associated with natural gums.23, 24 However, CPG showed higher peak intensities across all major regions, implying a greater concentration of active functional groups that may influence its performance as a pharmaceutical excipient. Cocoa pod gum exhibits greater thermal sensitivity and is more suitable for low-temperature processing; therefore, its use requires careful handling to prevent degradation. In contrast, XNG demonstrates higher thermal stability, making it ideal for thermally intensive applications. The potential physicochemical interactions between metronidazole and CPG, evaluated with FTIR, confirmed the absence of new absorption bands or significant peak shifts, indicating that metronidazole and XNG are chemically compatible.

The mechanical properties of tablet formulations are important factors in determining their ability to withstand stresses during manufacturing, packaging, transportation, and administration without compromising tablet integrity.25 As shown in Table 6, increasing the concentrations of both CPG and XNG led to greater tablet hardness and reduced friability, indicating enhanced mechanical strength and cohesive integrity. This trend is consistent with the expected behavior of binders, where higher polymer content promotes interparticulate bonding, adhesion and cohesion during compression, resulting in stronger tablets. It also aligns with the results of the mechanical strength of compacts reported in Table 5.25, 26 The differences observed in the mechanical properties of these gums may be attributed to the inherent physicochemical characteristics and smaller particle size of XNG, which facilitate more efficient particle packing and binding during compression. Literature indicates that smaller particle sizes enhance interparticulate contact, promoting stronger bonding and increased tensile strength in tablets.27 Moreover, the prolonged disintegration time observed in XNG-based tablets could be a direct consequence of stronger interparticulate bonding. This is further supported by the Py and PK values obtained in this study, which align with the superior compressional behavior and binding efficiency of XNG. The in vitro drug release study of metronidazole tablets was conducted to evaluate the influence of binder type and concentration on the drug’s release profile. The results revealed that drug release was both time- and concentration-dependent, with the percentage of drug released increasing over time but decreasing with increasing binder concentration. Tablets formulated with XNG exhibited a more pronounced retardation in drug release compared with those containing CPG. This observation may be attributed to the higher viscosity and mechanical strength of XNG, as evidenced by the data presented in Tables 2 and 6.

The elevated viscosity of XNG contributes to the formation of a dense hydration layer and gel matrix upon contact with the dissolution medium, thereby extending the diffusional path length and impeding drug diffusion through the gel layer.28 Furthermore, the enhanced mechanical strength resulting from XNG’s plastic deformation characteristics produces tablets with greater compact density and lower porosity. This structural compactness limits the penetration of the dissolution medium, reduces surface area exposure, and ultimately delays the drug dissolution process.29

Conclusions

The study demonstrates that both CPG and XNG are effective natural binders in metronidazole tablet formulations. An increase in binder concentration resulted in improved mechanical properties and slower disintegration and drug release. Xanthan gum produced compacts with higher hardness and slower drug release, attributed to its higher viscosity, greater plastic deformation capacity, and stronger interparticulate bonding. On the other hand, CPG produced tablets with faster disintegration and higher drug release, indicating its potential suitability for immediate-release formulations. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy results confirmed no incompatibility between the gums and metronidazole. These findings affirm the applicability of CPG as a promising, sustainable and biocompatible alternative to conventional binders.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.