Abstract

Background. Ethylene oxide (EO) sterilization is the most used sterilization method for disposable medical devices. Its popularity is based on the fact that it can be executed on industrial scale on full pallets of packed products and the fact that many materials are compatible with this sterilization technique.

Objectives. This article describes an introduction to EO as a sterilization technique and further studies on the compatibility of medical grade plastics with EO sterilization.

Materials and methods. Fourteen different healthcare polymer grades have been exposed to EO. This includes frequently used polyethylenes, polypropylenes, polyesters, and polycarbonates. Their mechanical and optical properties before and after exposure with EO were determined.

Results. After both the statistical analysis and a comparison with the accuracy of the measurement system, it can be concluded that all tested polymers retained their mechanical properties as measured by tensile and Izod impact testing after 1 sterilization cycle. Optical measurements showed that only 2 of the polymer grades had a minor discoloration, while all other materials had a very limited color change.

Conclusions. It has been shown that all families of plastics typically used in disposable medical products can be sterilized with EO without significant change in properties as determined on standardized test specimen.

Key words: infection control, sterilization, polymers, plastics, ethylene oxide

Background

Treating patients in a hospital requires sterile medical devices. Care must be taken to ensure that their health benefits from treatment and does not deteriorate due to the infamous “hospital-acquired infections”. Patients are vulnerable human beings who can easily contract infections, especially when their natural barrier, i.e., the skin, is open or damaged through surgery or wounds. Every tool used under these circumstances must be sterile. Devices may be reusable (cleaned and sterilized) or single-use (pre-sterilized and discarded). Sterilization is defined as the process that eliminates microbial life, including transmissible agents such as fungi, bacteria, viruses, and spores, from a surface, fluid or any material that will come into contact with a patient.1, 2, 3 Sterilization can be performed using various methods, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The most common terminal techniques are listed in Table 1. Terminal sterilization refers to the process in which the sterilizing step is applied after the production and packaging of the devices or drug formulation. The packaging maintains the product’s sterility until use once the sterilization process is complete. Material compatibility with sterilization techniques has been widely discussed in journal publications, books and industrial guidelines.1, 4, 5, 6

For each technique, typical application areas are indicated in Table 1. The industrial space refers to large-scale production environments, such as those for medical devices or pharmaceutical formulations. The professional space includes dedicated sterilization departments in hospitals or external sterilization service providers. The general space refers to local medical practices, dental offices and similar settings. While the location and scale of sterilization are not necessarily critical, it is within the industrial application space that single-use devices, primarily composed of plastics, are sterilized. Here, approx. 45% of sterilization is performed using radiation techniques and 50% using ethylene oxide (EO).7, 8, 9 For this reason, it is of paramount importance to establish material compatibility with these sterilization methods. The professional and general application areas mainly involve reusable tools, which are typically manufactured from metal or, in some cases, from high-end engineering plastics.

Radiation techniques are widely used, with gamma sterilization being the most common method today. It is estimated that around 40% of all single-use medical devices are sterilized by gamma radiation.8 The advantage of this method is that it can be applied under ambient conditions and to full pallets of products in their primary and secondary packaging as the final step before shipment. This technique is typically performed at dedicated facilities, as it requires a cobalt-60 (⁶⁰Co) radioactive source, which necessitates specific permits, expertise and safety measures. Plastics show variable compatibility with gamma radiation.4

Most materials retain their performance but may exhibit a color change. A few, however, can deteriorate and lose functionality. Notably, polypropylene (PP) requires specific stabilization, as it is highly sensitive to radiation. Electron beam and X-ray sterilization are alternative applications of ionizing radiation and have effects on materials similar to those of gamma radiation.5 UVC radiation is commonly used for water and air disinfection but gained prominence in medical applications during the COVID-19 pandemic.6

Temperature-based sterilization can be performed using either dry heat or steam exposure. The excellent heat transfer properties of steam allow for shorter sterilization cycles at lower temperatures compared with dry heat. However, both heat and humidity can significantly influence material properties. The advantage of these techniques is their wide availability and compatibility with most metals, ceramics and glass, making them the preferred methods in doctors’ offices, hospital sterilization departments and sterilization service facilities.

Chemical disinfection is not strictly a sterilization technique but is related in that it aims to disinfect surfaces by eliminating or reducing the microbial load. A variety of chemical wipes are used to clean stationary surfaces and equipment in medical environments. Material compatibility varies greatly and depends on the specific chemicals used.

In gas-based sterilization, EO is the only method used on an industrial scale for single-use devices. Its use in sterilizing single-use medical devices is roughly comparable to that of gamma radiation, accounting for an estimated 40–50%.8, 9 The use of other gases is increasing, but their application remains relatively limited. Hydrogen peroxide, in vapor or plasma form,10, 11 and ozone12 can oxidize organic molecules and attack DNA, proteins and other microbial components, thereby preventing their transmission and replication. These gases can be generated in situ, offering logistical advantages and leaving no residues on sterilized devices.

Objectives

This article briefly discusses the fundamentals of EO sterilization. For more detailed information, several comprehensive review papers are available.7, 13 In addition, the effects of EO on commonly used plastics are examined.

Materials and methods

Outline

Ethylene oxide readily alkylates polar groups such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups. The reaction is exothermic and occurs rapidly at ambient temperatures. This reactivity gives EO its sterilizing capability: When polar groups in proteins and DNA are alkylated, the microbes carrying them are rendered nonviable and unable to replicate or multiply. However, this strong sterilizing action also makes EO gas toxic. It must be handled under strictly controlled conditions with extreme care. Another associated risk of EO is its flammability. Despite these hazards, the use of EO for sterilization offers many advantages. Unlike gamma radiation, it does not require the handling of dangerous or highly regulated radioactive isotopes. It can also be applied to temperature- and radiation-sensitive devices. Most materials are reported to be compatible with EO sterilization. The Advancing Safety in Health Technology (AAMI) Technical Information Report: Compatibility of Materials Subject to Sterilization lists many material classes and provides an initial indication of their compatibility. In the section covering EO, only acrylics received a rating lower than “excellent”.4 All terminal sterilization techniques are applied to packaged products. In the case of EO sterilization, the gas must be able to enter and exit the packaging easily to achieve an acceptable sterilization cycle duration. A practical solution is to use packaging that is at least partially made of permeable materials such as paper or nonwoven plastic fabrics. These materials must meet strict pore size specifications to ensure that gases can penetrate efficiently while preventing microbial passage. Otherwise, sterility cannot be maintained during transport and storage.

A typical EO sterilization cycle proceeds as follows14:

– The load to be sterilized is placed in an airtight sterilization chamber.

– Air is removed using a vacuum and replaced with an inert gas such as nitrogen.

– A humidification step is carried out by injecting steam.

– EO is then introduced into the chamber. Typical concentrations are within the range of 450–1200 mg/L, at temperatures between 37°C and 63°C and relative humidity of 40–80%, for a duration of 1–6 h. Higher concentrations may cause difficulties in removing residual EO from the product, while lower concentrations may result in incomplete sterilization.

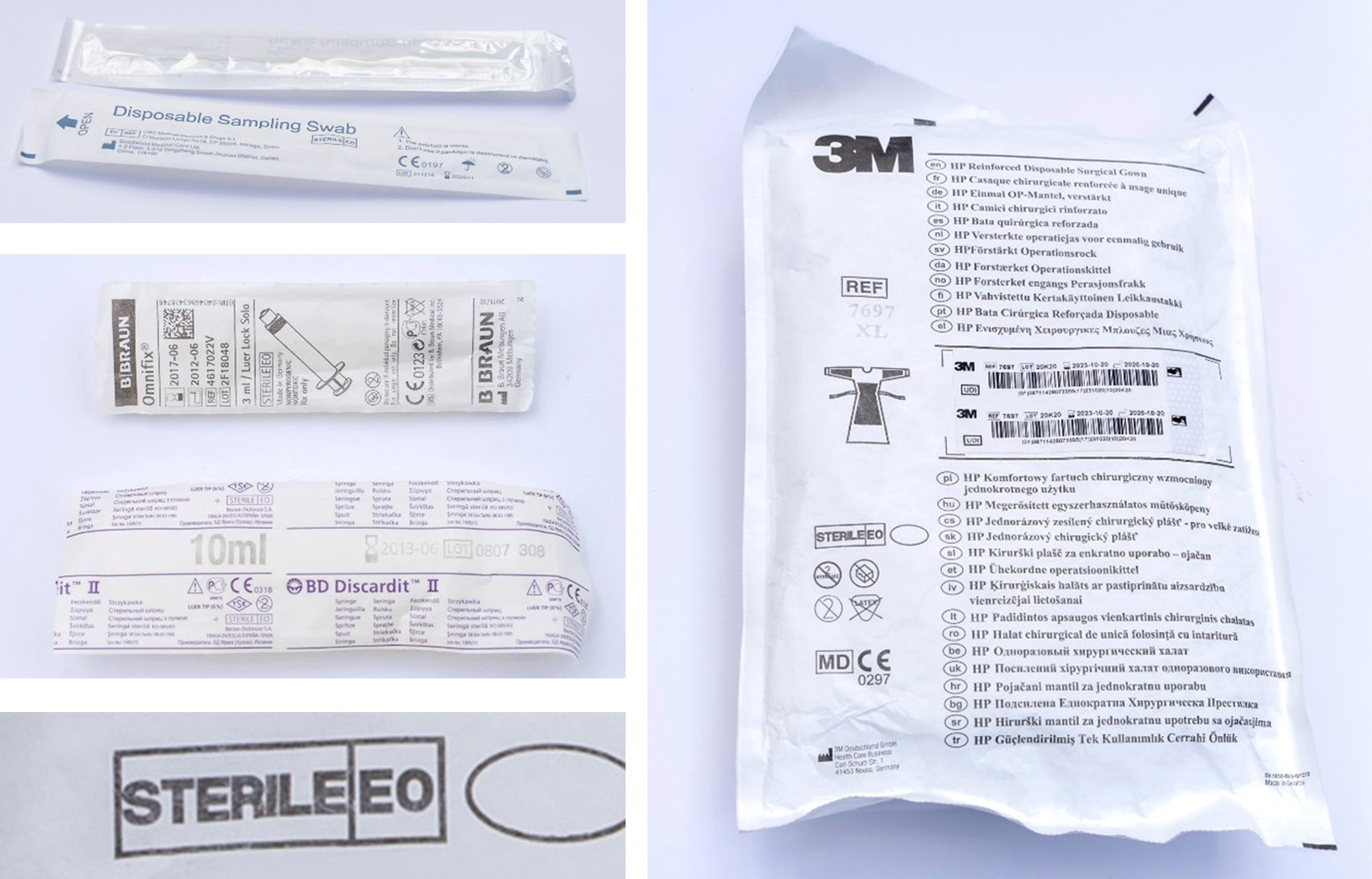

The products are degassed using alternating vacuum and nitrogen cycles. To further reduce residual EO levels, the sterilized items may be stored in an aeration chamber for 8 h up to 1 week. Sterilization efficiency depends on careful control of EO concentration, humidity, temperature, and exposure time. For each product and packaging combination, the speed and depth of the vacuum must be optimized. When the secondary packaging is also compatible with the process, sterilization can be applied to full pallets or containers. Figure 1 shows examples of gas-permeable packaging. The packaging consists of 2 parts: 1) a transparent polyethylene film, and 2) a white, opaque, gas-permeable layer made of either paper or nonwoven fabric. DuPont’s Tyvek®, a nonwoven material made from HDPE fibers, is frequently used for this purpose.15 The 2nd part allows air, water vapor and EO gas to pass in and out of the package during the various stages of the sterilization cycle without causing damage. Additionally, the pore sizes in this layer must be small enough to prevent the entry of microbes, viruses, spores, and bacteria after sterilization. The shelf life of sterilized products typically ranges from 3 to 5 years, requiring the packaging to maintain its integrity throughout this period.16 One disadvantage specific to EO sterilization is the presence of undesirable residual chemicals in sterilized products.17, 18 These products may contain traces of EO, ethylene glycol (EG), and ethylene chlorohydrin (ECH).17 All 3 substances are toxic, and EO additionally possesses carcinogenic properties. Ethylene glycol forms through the reaction of EO with water (humidity), while ECH is produced when EO comes into contact with free chloride ions, such as those present in polyvinyl chloride. Patients may develop allergic reactions upon exposure to these residues, particularly with repeated use.19, 20 For patients with chronic conditions requiring regular treatment, such as those undergoing dialysis, EO-sterilized devices are typically avoided, and radiation-sterilized consumables are preferred. Because of these disadvantages, as well as the dangers and environmental impact of EO emissions, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has launched a program to support reducing EO concentrations and exploring alternative sterilization methods.21 Nevertheless, EO sterilization remains indispensable due to its large-scale applicability and broad material compatibility. With approx. 20 billion medical devices sterilized annually by EO in the USA alone, concerns have arisen that facility closures driven by environmental regulations could significantly impact the availability of essential medical devices.2

Methods

The plastic materials were molded according to ISO 294-1:2017 using an Engel 90t injection molding machine to produce tensile bars with ISO 527/1A dimensions and impact bars measuring 80 × 10 × 4 mm. Samples for color measurements were also prepared to evaluate color changes following EO sterilization. The materials were sterilized with EO in accordance with the ISO 11135:2014 standard testing method, and the samples were packed in open plastic bags.

Tensile properties were measured at a crosshead speed of 50 mm/min following ISO 527-1:2019, while impact strength was determined according to ISO 180:2023. Color measurements were performed using a Konica Minolta CM-5 spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) in accordance with ASTM E313-96, employing illuminant D65 in the CIELAB color space.

The 3 coordinates represent color positions along the following axes: L* (lightness, 0 = black, 100 = white), a* (negative = green, positive = red) and b* (negative = blue, positive = yellow). The Yellowness Index (YI) is a calculated parameter used to describe shifts in color toward the yellow spectrum.

Materials

Dedicated healthcare grades from SABIC’s portfolio were tested. These materials are manufactured under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) to meet the stringent quality standards of the medical industry. The selected materials are used in a wide range of applications, including drug delivery devices (e.g., inhalers, injection pens, insulin pumps), diagnostic devices (e.g., glucose monitors, wearables), syringes, ampoules (e.g., for eye drops), primary pharmaceutical packaging, tubes, intravenous (IV) bags, and blood filters, among others. Although SABIC does not supply materials for implant applications, other HDPE grades are known to be used in that field, e.g., as bone replacement materials.22 Many of these applications can employ EO for sterilization purposes. The following materials were used: PCG07 low-density polyethylene (LDPE), PCG453 and PCG863 high-density polyethylene (HDPE), PCGR40 polypropylene random copolymer with ethylene (PP r), 58MNK10 polypropylene impact copolymer with ethylene (PP icp), PCGH19 polypropylene homopolymer (PP h), CYCOLAC™ HMG94MD and HMG47MD acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene copolymers (ABS), VALOX™ HX325HP and HX312C polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) polyesters, LEXAN™ HP2REU and HP4REU polycarbonate (PC), CYCOLOY™ HC1204HF PC/ABS blend, and XYLEX™ HX7509HP blend of PC and polycyclohexylenedimethylene terephthalate glycol-modified (PCTG) polyester. All materials were processed according to their respective datasheet recommendations, including temperature settings and pre-drying conditions.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab® v. 17.1.0 (Minitab Inc., State College, USA). Mechanical testing was typically conducted on 5 samples for each material before and after EO exposure. The 5 individual measurements were used to calculate an average value, which served as the single data point for each impact or tensile test. In the subsequent statistical analyses, the individual measurements and their results were evaluated. For all datasets (n = 5), normality tests were performed. The Anderson–Darling, Ryan–Joiner, and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests generally yielded consistent outcomes. When normality was confirmed, an F-test was used to compare variances between 2 datasets collected before and after EO exposure. A two-sample t-test was performed on the same 2 datasets to test the null hypothesis that their means were equal. When equal variances were confirmed, the “assume equal variances” option was applied for the t-test. These analyses were conducted for all impact and tensile test results. For tensile elongation at break, an error occurred during some tests, causing the procedure to stop once 100% elongation was reached. This affected several unexposed samples. For these cases, a comparison was made between the 5 post-exposure measurements and the average value of unexposed samples obtained from historical data, using a one-sample t-test. Table 3 indicates which samples this applies to. Further details on hypothesis testing can be found in standard references on process improvement methodologies.23

Results and Discussion

Mechanical properties

The data obtained before and after EO exposure were first compared statistically using the approach described in the Materials section. This process eliminated most apparent differences. Average values for impact and tensile properties are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Differences between the 2 datasets are reported only when the statistical analysis (two-sample t-test) indicated significance at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). It should be noted that statistically significant differences do not necessarily correspond to the numerically largest absolute or relative changes. For all datasets comparing results before and after EO exposure, where statistical analysis confirmed significance, the practical significance of each difference was evaluated. This was done by comparing the magnitude of the change to the long-term standard deviation (SD) of a repeatedly measured Statistical Quality Control (SQC) sample. Table 4 presents the values obtained for a LEXAN™ PC sample measured over a 9-month period. The variation observed represents the inherent variability of the measurement system itself over that timeframe, independent of any sample variation. It is important to note that the SQC data were obtained in accordance with the relevant ISO test protocols, meaning that 5 measurements were taken to produce 1 average value, representing a single data point. The averages and standard deviations (SDs) presented in Table 4 are based on 36 such data points. In contrast, the statistical analyses in this report used individual measurements rather than averages of 5. One could argue that either the absolute or relative value of the SQC SD should be considered when comparing observed differences between samples to measurement variation across different material types. In any case, the differences observed in the notched Izod impact results are not practically relevant. For unnotched Izod impact, the values for the PP impact copolymer decreased by 8 kJ/m², while those for one of the PBT materials (HX312C) decreased by 12 kJ/m². The relative difference was below 10% in both cases and less than 3 times the relative SD of the SQC measurements. However, the absolute difference exceeded 3 times the SD. A few values for modulus and most values for stress and strain at the yield point showed statistically significant changes following sterilization, but the magnitude of these changes was limited – less than 3 times the SQC SD. The strain at break was not recorded for the SQC material due to the high variability between measurements. In the literature, stress at yield and strain at break are commonly used to assess the compatibility of materials with sterilization techniques or chemical exposure. Although strain at break is highly sensitive to small material changes, it also exhibits relatively high variability (SD), often rendering observed differences statistically insignificant. Based on the data showing statistical differences, all tested materials can be classified as “compatible.”

Color retention

Color differences before and after EO sterilization of plastic parts were compared. Unpigmented or natural polymers are typically either colorless (transparent) or opaque (white). The development of yellowness in an unpigmented polymer or plastic part often indicates degradation. High temperatures or exposure to UV light or chemicals can cause chemical or physical changes in the polymer, resulting in yellow discoloration. During the polymer compounding process, yellowing may also occur due to factors such as photo-oxidation and thermal degradation.

A change in the Yellowness Index (ΔYI) can serve as a quality control specification when manufacturing unpigmented plastic parts, such as blow-molded bottles or extruded sheets. Table 5 presents the color measurements for the materials investigated. Five measurements were taken for each sample, and the averages were recorded both before and after EO sterilization. Delta values are reported only for datasets in which the difference between “before” and “after” values was statistically significant (p < 0.05). As shown in Table 5, most samples exhibited similar YI values before and after sterilization, with only minor differences, except for 3 materials – 1 HDPE (PCG863) and the 2 ABS samples. The ΔYI for these 3 materials were greater than those of the others, indicating an increase in yellowness following EO sterilization. All other samples maintained their YI values after sterilization. Photographs of the parts before and after sterilization, provided in the supplementary information, confirm the absence of visible changes in appearance. The supplementary material also includes Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra for the 3 samples with statistically significant ΔYI values, showing no detectable chemical changes or signs of molecular degradation.

Limitations

The conclusions of this study should be interpreted with the usual caution. The results are based on a single set of experiments and have not been replicated over time. Although the experimental conditions reflect typical real-life applications, variations in molding or sterilization parameters may yield different outcomes. Therefore, it is essential that users of these materials conduct their own evaluation to confirm the suitability of the material for the intended application.

Conclusions

Ethylene oxide remains the most widely used sterilization technique for single-use medical devices due to its large-scale applicability and broad material compatibility. This study confirms the general statements from the literature, demonstrating that EO sterilization is indeed compatible with a wide range of medical-grade plastics.4

The study focused on material stability parameters most relevant to end-use applications: tensile strength, impact resistance, and color retention. Based on statistical evaluations and comparisons with long-term measurement variation, only minimal changes were observed as a result of the sterilization process. The variations detected were minor, and according to commonly applied criteria (<10% change), all tested plastics can be classified as compatible with a single cycle of EO sterilization..

Supplementary data

The supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15681248. The package includes the following files:

20250611 EO full data.csv : The full dataset of measurements both mechanical and optical

Supplementary Fig. 1. Photographs of samples 1–7 before and after EO sterilization.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Photographs of samples 8–14 before and after EO sterilization.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Comparison of ATR FTIR spectra of PCG863 HDPE before and after EO sterilization.

Supplementary Fig. 4. Comparison of ATR FTIR spectra of HMG94MD ABS before and after EO sterilization.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Comparison of ATR FTIR spectra of HMG47MD ABS before and after EO sterilization.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.