Abstract

Background. The polymer matrix of Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm contributes to its resistance to a broad spectrum of antibiotics and poses a significant public health threat.

Objectives. The present study aims to use hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MICs) to improve cefotaxime efficiency against cefotaxime-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) by disrupting the biofilm polymer matrix.

Objectives. The present study aims to determine whether sub-MICs of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) can enhance the efficacy of cefotaxime against CRKP by disrupting the biofilm polymer matrix.

Materials and methods. Klebsiella pneumoniae was isolated from 140 burn wound samples. The effect of cefotaxime and sub-MICs of H2O2 on biofilm formation by pretreated K. pneumoniae was evaluated. A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to examine the effect of H2O2 sub-MICs on the biofilm matrix. The synergistic effect of H2O2 sub-MICs on the susceptibility of CRKP to cefotaxime and on the structure of the biofilm polymer matrix was also assessed.

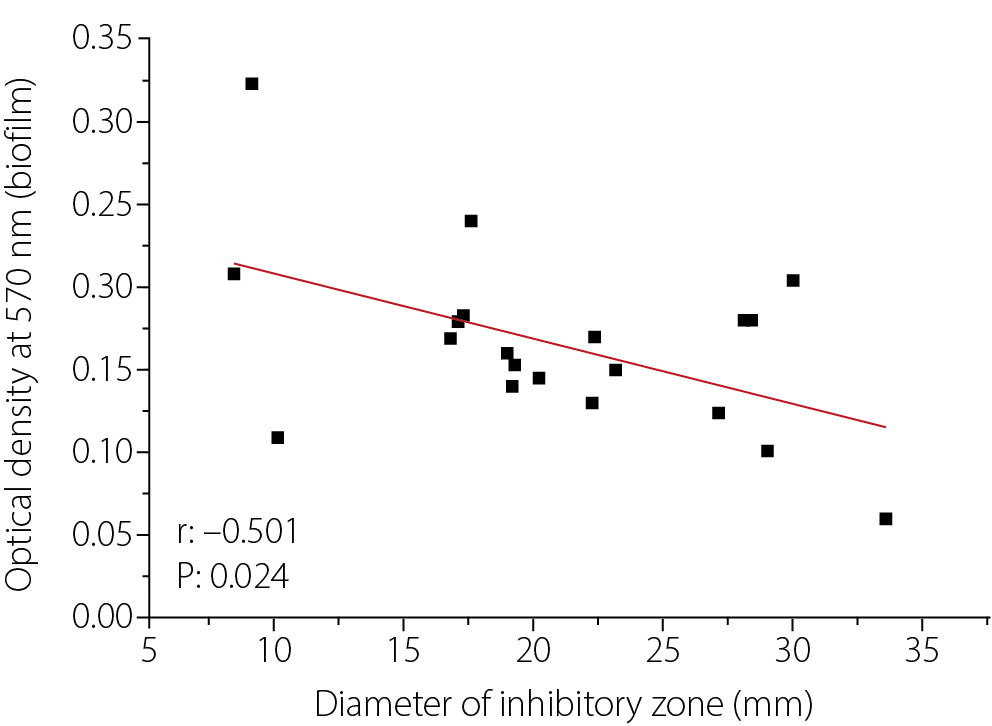

Results. A moderately high incidence of wound infections caused by CRKP was observed. A statistically significant negative correlation was found between biofilm formation and bacterial susceptibility to cefotaxime (r = –0.501, p = 0.024). Treatment with various sub-MICs of H2O2 and cefotaxime reduced biofilm formation on polystyrene surfaces by the K. pneumoniae Kp10 isolate. Specifically, exposure to H2O2 at 1/8 MIC induced the formation of pores and channels within the biofilm matrix, resulting in a looser biofilm structure. A synergistic effect (fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index ≤ 0.5) was observed, where sub-MICs of H2O2 decreased the MIC of cefotaxime against Kp10 from 1,000 µg/mL to 250 µg/mL at ½ and ¼ MIC of H2O2, and produced a strong additive effect with a reduction to 500 µg/mL at other sub-MICs. The combination of H2O2 sub-MICs and cefotaxime was more effective in reducing biofilm formation than either agent used alone.

Conclusions. Sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of H2O2 exhibited synergistic to strongly additive effects in enhancing the antibacterial activity of cefotaxime against CRKP and in reducing biofilm formation by the K. pneumoniae Kp10 isolate. This effect appears to be mediated by disruption of the biofilm polymer matrix, which may contribute to improved infection control.

Key words: biofilm polymer, cefotaxime, scanning electron microscope, sub-MICs, synergy

Background

The polymer matrix of bacterial biofilms is a highly organized extracellular environment composed of macromolecules such as polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. This matrix is fundamental to the biofilm’s architecture and plays a key role in protecting bacterial cells.1 The polymer matrix also contributes to the persistence of bacterial populations and their protection against external environmental factors, including antibiotics.2 In clinical settings, the biofilm polymer matrix acts as a physical barrier that limits antibiotic penetration into bacterial cells, promotes chronic infection and significantly contributes to antibiotic resistance, particularly in Gram-negative bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae.3, 4 The microenvironment within the deeper layers of the biofilm matrix is characterized by nutrient deprivation, hypoxia and altered pH, leading to metabolic adaptations in bacterial populations and the induction of a persistent state that further enhances antibiotic resistance.5

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen responsible for a wide range of healthcare-associated infections, including pneumonia, urinary tract infections, wound infections, and, in some cases, sepsis. A major virulence factor of K. pneumoniae is its ability to form extensive polymeric biofilm masses on both biotic and abiotic surfaces.6 This species exhibits resistance to a broad spectrum of antibiotics through multiple mechanisms, including β-lactamase production, efflux pump activity and biofilm formation, making such infections particularly difficult to treat.7 It can colonize medical devices such as urinary catheters, endotracheal tubes and central venous catheters,8 as well as hospital surfaces including bed rails, door handles and surgical instruments.9 Klebsiella pneumoniae also forms biofilms on plastic and metal surfaces such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), stainless steel and polystyrene.10 Furthermore, it adheres to epithelial tissues, including the urinary tract epithelium.11 On these surfaces, K. pneumoniae exhibits increased tolerance to antibiotics, largely mediated by its dense polymeric matrix, which restricts antibiotic diffusion.12 The rising incidence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) K. pneumoniae strains in recent years underscores the urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies aimed at enhancing antibiotic efficacy through biofilm modulation.13

One promising strategy involves the use of sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (sub-MICs) of non-antibiotic agents to weaken the biofilm matrix and enhance antibiotic penetration into embedded bacteria. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a reactive oxygen species (ROS) naturally produced by immune cells, has a well-documented impact on biofilm architecture.14 While the bactericidal effects of high concentrations of H2O2 are well established, the influence of sub-MIC levels of H2O2 on the polymeric biofilm matrix of K. pneumoniae remains poorly characterized in the literature.

This study focuses on the effects of sub-MICs of H₂O₂ on the biofilm polymer matrix of K. pneumoniae and its potential influence on antibiotic interaction. Investigating biofilm modulation through oxidative stress may provide a better understanding of approaches to improve the effectiveness of existing antibiotics.

Previous studies have shown that hydroxyl radical formation induced by bactericidal antibiotics represents the final stage of an oxidative damage pathway leading to bacterial cell death.15 In combination with antibiotics, H2O2 has demonstrated the potential to reverse antibiotic resistance by disrupting bacterial defense mechanisms, thereby enhancing antibiotic efficacy. A previous study by Alkawareek et al. reported the synergistic antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles and H2O2 against Staphylococcus and Escher-

ichia coli. However, no prior research has investigated the synergistic effect of sub-MICs of H2O2 on the susceptibility of K. pneumoniae to antibiotics.16

Objectives

The objective of this study is to investigate the effects of sub-MIC concentrations of H₂O₂ on the structure and density of the biofilm polymer matrix in K. pneumoniae and to evaluate how these changes may influence the activity of cefotaxime.

Materials and methods

Isolation and identification of bacteria

Infected wound samples were collected aseptically from 140 inpatients with burn wound infections admitted to the Burns and Wounds Department at Baghdad Teaching Hospital (Baghdad, Iraq). Prior to sample collection, necrotic tissue and any residual ointments were carefully removed by a trained technician. None of the patients had received antibiotic treatment for at least 72 h before sampling, and all provided informed consent to participate in the study. Wound swabs were cultured on MacConkey agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Large, mucoid, pink colonies (lactose-fermenting) were collected and subjected to Gram staining, followed by standard biochemical tests, including oxidase, indole, urease, and citrate utilization assays. Identification of K. pneumoniae isolates was confirmed using the VITEK instrument (VITEK® DensiCHEK™; BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and fluorescence system (bioMérieux) with the ID-GNB card. The bacterial isolates were preserved in 20% glycerol nutrient broth at −20 °C and subcultured weekly on nutrient agar.17 The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Baghdad, Iraq (approval No. CSEC/1124/0113, issued on November 27, 2023).

Kirby-Bauer method

The Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method was used to identify cefotaxime-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP). A bacterial suspension adjusted to the turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard was spread onto Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA; HiMedia). Cefotaxime disks (30 µg; Bioanalyse, Ankara, Turkey) were placed on the MHA plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Following incubation, the diameters of the inhibition zones around the cefotaxime disks were measured and interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoint guidelines to classify isolates as susceptible (S), intermediate (I) or resistant (R) to cefotaxime.18

Minimum inhibitory concentration

The microdilution method described by Al-Mutalib and Zgair was used to determine the MICs of cefotaxime (AdvaCare Pharma, Durham, USA) and H2O2 (Merck Millipore, St. Louis, USA) against the CRKP isolate (Kp10). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration of the antimicrobial agent that completely inhibited visible bacterial growth.19, 20

Biofilm formation

The microdilution method combined with a spectrophotometric assay using crystal violet was employed to assess biofilm formation in 20 K. pneumoniae isolates.15, 16, 17 The method has been described in detail in previous studies.19, 20, 21 Briefly, 100 µL of sterile tryptic soy broth (TSB; HiMedia) was added to the wells of a flat-bottom polystyrene tissue culture plate. Then, 5 µL of CRKP suspension (0.1 OD₆₀₀ of an overnight bacterial culture, washed 3 times with sterile TSB) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, the TSB was discarded and the plates were washed 3 times with distilled water. The plates were then air-dried and stained with 100 µL of 0.4% Hucker crystal violet for 15 min, followed by 5 washes with distilled water. After drying, 100 µL of anhydrous ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the bound dye. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek 800 TS; BioTek, Winooski, USA). The experiment was repeated 3 times.

Effect of sub-MICs on biofilm formation

In this experiment, the effect of different sub-MICs of H₂O₂ or cefotaxime on biofilm formation by the CRKP isolate that exhibited the highest biofilm-producing capacity was evaluated. A similar biofilm formation assay was performed with slight modifications. Instead of using TSB alone, serial dilutions of sub-MICs of H₂O₂ or cefotaxime were prepared in TSB and added to the wells of a flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plate. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and washed 3 times with distilled water. The wells were then stained with crystal violet, and after air drying, anhydrous ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the bound dye. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek 800 TS). The experiment was repeated 3 times.21

Scanning electron microscopy

The procedure described by Gomes and Mergulhão was followed to examine the biofilm of the CRKP isolate Kp10 using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) after treatment with a sub-MIC of cefotaxime.²² Briefly, biofilm smears were prepared on sterile glass slides and treated with 1⁄8 MIC of cefotaxime to evaluate the effect of the sub-MIC on the biofilm polymer matrix. After staining, the slides were examined under a scanning electron microscope (Apreo 2 ChemiSEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA).

Effect of sub-MICs of H2O2

on cefotaxime MICs

The two-dimensional microdilution method (checkerboard assay) using a 96-well U-shaped polystyrene microtiter plate was employed to evaluate the effect of different sub-MICs of H2O2 on the susceptibility of K. pneumoniae (CRKP isolate exhibiting the highest biofilm-forming ability) to cefotaxime, expressed in terms of MIC values. Briefly, 100 µL of sterile MHA was added to each well. A horizontal twofold serial dilution of cefotaxime, ranging from 2,000 μg/mL to 1.95 µg/mL, was prepared and applied across all wells in each row of the plate (wells 1–11). A vertical twofold serial dilution of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂; 30% stock solution: Merck Millipore) ranging from 1/160 to 1/10,240 was prepared in rows A–G of the microtiter plate. Subsequently, 5 µL of K. pneumoniae suspension (optical density (OD) of 0.1 at 600 nm) was added to each well. The plates were gently shaken and incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

The lowest antibiotic concentrations that completely inhibited bacterial growth were recorded as the MIC. Row H served as the first control, representing the MIC of cefotaxime in the absence of H2O2. Rows A–G demonstrated the effect of different H2O2 dilutions (sub-MICs) on the MIC of cefotaxime. Several control groups were included: 1) wells containing different H2O2 dilutions (sub-MICs in MHA) with the K. pneumoniae Kp10 isolate, 2) wells containing only MHA and bacteria, 3) wells containing only MHA, and 4) wells containing different cefotaxime dilutions (in MHA). The experiment was performed in triplicate. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index was calculated using the following equation:

Effect of combination of sub-MICs of H2O2 and cefotaxime on biofilm formation

A similar procedure was followed to evaluate the effect of H2O2 on MICs of cefotaxime against the CRKP isolate exhibiting the highest level of biofilm formation, with minor modifications. Tryptic soy broth was used instead of MHA, and a 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plate was used instead of a U-shaped plate. Following incubation, the plates were air-dried and stained with 100 µL of 0.4% Hucker crystal violet for 15 min, then washed 5 times with distilled water. After drying, 100 µL of anhydrous ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the bound dye. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek 800 TS). The experiment was performed in triplicate.19, 20, 21

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed and graphs were generated using Origin software v. 8.6 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA). Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE). Differences between groups were assessed using Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Correlations were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

Results

Bacterial isolates

Twenty isolates of K. pneumoniae were obtained from 140 infected wound swabs collected from inpatients with severe wound infections. The bacterial species were identified using microscopic and biochemical tests, and further confirmed with the VITEK 2 system (bioMérieux). The incidence rate of wound infections caused by K. pneumoniae was 14.28%.

Antibiotic susceptibility and biofilm formation

The Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method was used to determine the susceptibility of K. pneumoniae isolates to cefotaxime, thereby identifying CRKP, cefotaxime-susceptible (CSKP) and intermediate isolates. As shown in Table 1, 13 isolates were resistant to cefotaxime, 6 were susceptible and 1 exhibited intermediate susceptibility. Among the tested isolates, Kp10 produced the highest level of biofilm formation, followed by Kp1, whereas Kp18 showed the lowest biofilm formation on polystyrene microtiter plates.

The Kp10 isolate (CRKP), which produced the most robust biofilm and exhibited the smallest zone of inhibition in the cefotaxime disk diffusion assay, was selected for further experiments. In this study, the MIC of cefotaxime against Kp10 was 1,000 µg/mL, while the MIC of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was 0.046% (equivalent to 0.468 mg/mL), corresponding to a 1⁄640 dilution of the 30% H2O2 stock solution.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between biofilm formation and the inhibition zone diameter of cefotaxime against 20 clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae. A statistically significant negative correlation was observed between biofilm formation and the susceptibility of K. pneumoniae to cefotaxime, as indicated by the inhibition zone diameter (r = –0.501, p < 0.05).

Effect of sub-MICs of cefotaxime or H2O2 on biofilm formation

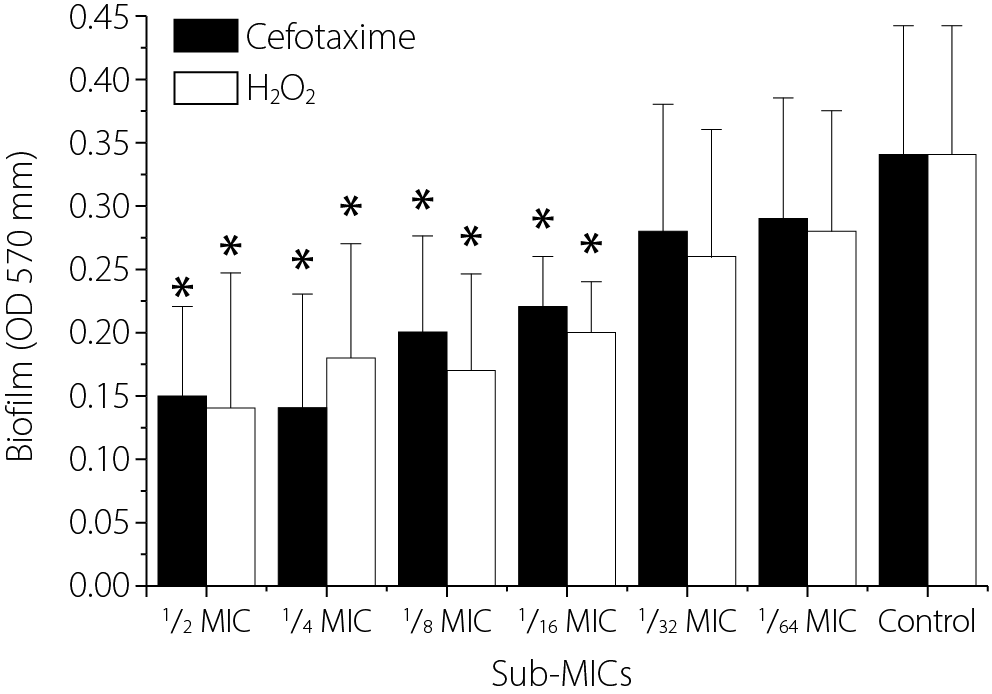

The effect of sub-MICs of H2O2 and cefotaxime on biofilm formation by the K. pneumoniae Kp10 isolate was evaluated. The results showed that both cefotaxime and H₂O₂ significantly reduced biofilm formation at higher sub-MIC levels (½ to 1⁄16 MIC) (p < 0.05). The reduction was minimal at lower sub-MICs (1⁄32 and 1⁄64 MIC) compared with the control (biofilm formation of Kp10 without treatment). At ½, 1⁄8, 1⁄16, 1⁄32, and 1⁄64 MIC, cefotaxime appeared to be more effective than H2O2 in reducing biofilm formation; however, no statistically significant differences were observed between the effects of H2O2 and cefotaxime at corresponding sub-MIC levels (p > 0.05).

Furthermore, at 1⁄32 and 1⁄64 MIC, neither treatment showed a significant effect on biofilm formation compared with the control levels (Figure 2). The results demonstrated that both cefotaxime and H2O2 reduced biofilm formation by K. pneumoniae Kp10 in a concentration-dependent manner at sub-MIC levels. The most pronounced effects were observed at ½ to 1⁄8 MIC, with cefotaxime exhibiting slightly greater biofilm inhibition than H2O2. These findings support the potential anti-biofilm activity of both agents at sub-MIC levels.

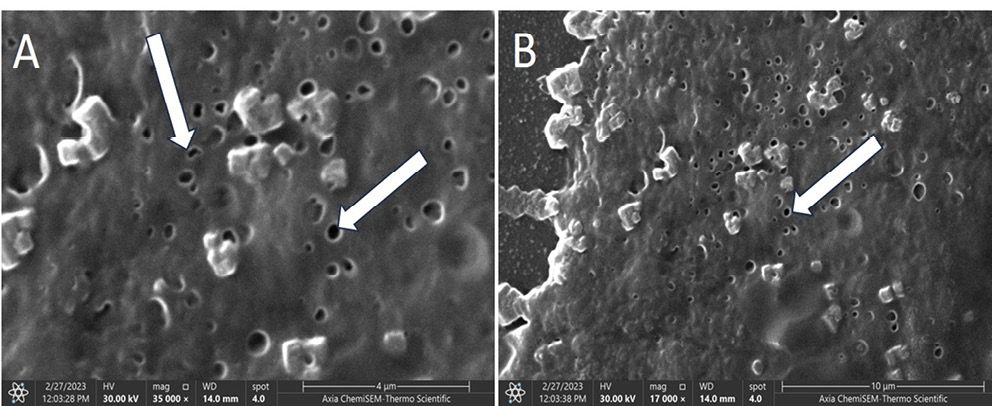

Effect of sub-MIC H2O2 on the biofilm polymer structure

To examine the effect of sub-MICs of H2O2 on the polymer structure of the biofilm, smears of K. pneumoniae (Kp10) biofilm were prepared under 1⁄8 MIC H2O2 stress (Figure 3). The SEM images revealed a disrupted and porous biofilm architecture, indicating that sub-MIC levels of H2O2 (1⁄8 MIC) compromise the integrity of the biofilm matrix. Arrows in the images highlight distinct pores and cavities, suggesting disruption and partial degradation of the exopolysaccharide (EPS), a key component responsible for the structural stability of the biofilm polymer matrix.

Figure 3A shows the biofilm surface exhibiting numerous perforations and EPS regions. Some bacterial cells appear embedded within or surrounded by partially degraded matrix material. The presence of pores indicates a loss of structural compactness and possible formation of water channels resulting from oxidative stress. Figure 3B, which depicts the biofilm under the same stress conditions at lower magnification, provides a broader view of the overall biofilm structure. Similar to Fig. 3A, pores and surface irregularities are evident. The matrix appears less dense and loosely organized, with fragmented regions and disrupted continuity.

The SEM images confirm that H2O2 at 1⁄8 MIC induces structural weakening of the biofilm matrix without complete eradication. The formation of pores likely increases biofilm permeability, facilitates greater penetration of antimicrobial agents and reduces the mechanical stability of the biofilm. Thus, the SEM observations demonstrate that pretreatment with 1⁄8 MIC H2O2 leads to marked porosity and disruption of the K. pneumoniae biofilm EPS matrix.

Effect of H₂O₂ on cefotaxime MICs

The effect of various sub-MICs of H2O2 on the susceptibility of the K. pneumoniae isolate Kp10 to cefotaxime is presented in Table 2. The results show that all tested sub-MICs of H2O2 reduced the cefotaxime MIC required to completely inhibit Kp10 growth compared with the control (cefotaxime MIC without H2O2). The greatest reduction was observed at ½ and ¼ MIC of H2O2, which decreased the cefotaxime MIC from 1,000 µg/mL to 250 µg/mL. Furthermore, sub-MICs of H2O2 at 1⁄8, 1⁄16, 1⁄32, and 1⁄64 lowered the cefotaxime MIC against Kp10 from 1,000 µg/mL to 500 µg/mL.

This study presents a novel observation that the anti-biofilm agent H2O2 enhances the susceptibility of the K. pneumoniae isolate Kp10 to cefotaxime. However, Kp10 remains classified as resistant to cefotaxime, as the MIC values remain above the susceptibility threshold defined by the CLSI guidelines for K. pneumoniae. The FIC index was calculated to determine the nature of the interaction between H2O2 and cefotaxime. The FIC indices for combinations of cefotaxime with ½, ¼, 1⁄8, 1⁄16, 1⁄32, and 1⁄64 MIC of H2O2 were 0.5, 0.5, 0.625, 0.526, 0.514, and 0.515, respectively. These results indicate a low synergistic effect at ½ and ¼ MIC levels and a strong additive effect at 1⁄8, 1⁄16, 1⁄32, and 1⁄64 MIC levels of H2O2 on the cefotaxime MIC. Overall, the present study demonstrates that sub-MIC levels of H2O2 exhibit an additive to mildly synergistic effect on the susceptibility of K. pneumoniae Kp10 to cefotaxime.

Effect of combination of H₂O₂ and cefotaxime on biofilm formation

Table 3 illustrates the effect of sub-MICs of H2O2 and cefotaxime on biofilm formation by the K. pneumoniae Kp10 isolate. The results show that the greatest inhibition of biofilm formation occurred when Kp10 was simultaneously exposed to higher sub-MICs of H2O2 (½ and ¼ MIC) and cefotaxime (½ and ¼ MIC), producing results comparable to those observed in MIC wells. In contrast, minimal inhibition of biofilm formation was observed when Kp10 was exposed to the lowest sub-MIC levels of both cefotaxime and H2O2 (1/64 MIC).

The results were compared with control 1, control 2 and control 3. This study is the first to demonstrate that the combined effect of sub-MICs of cefotaxime and H2O2 significantly reduced biofilm formation in the K. pneumoniae Kp10 isolate compared with exposure to sub-MICs of either agent alone (controls 1 and 2; p < 0.05). This observation provides insight into a potential mechanism by which sub-MIC levels of H2O2 and cefotaxime enhance the susceptibility of Kp10 to cefotaxime.

Discussion

The principal structural component of the biofilm biomass is its polymeric matrix, which is primarily composed of EPS, proteins and extracellular DNA. This matrix provides both mechanical stability and protective shielding against antibiotics.1 It functions as a physical and biochemical barrier, limiting antibiotic diffusion and facilitating horizontal gene transfer, thereby enhancing bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents.3, 4, 22 In K. pneumoniae, the capsular polysaccharide contributes significantly to antibiotic resistance and plays a crucial role in biofilm

formation.23

In K. pneumoniae, the biofilm polymer represents a significant clinical challenge, particularly in nosocomial infections and chronic conditions where antibiotic therapy often fails.2 The emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) K. pneumoniae strains have markedly increased morbidity and mortality among infected patients.²

In the present study, we demonstrated that exposure of K. pneumoniae biofilms to sub-MICs of H2O2 resulted in a marked reduction in the production of the biofilm polymer matrix. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that exposure to sub-MIC levels of H2O2 induced the formation of distinct pores within the biofilm structure, potentially facilitating antibiotic penetration. This effect significantly enhanced the antibacterial activity of cefotaxime, a third-generation cephalosporin. The primary finding of this study is that sub-MICs of H2O2 can disrupt the synthesis or stability of the extracellular biofilm polymer matrix. Our results indicate a significant decrease in total biofilm biomass and polymeric content following H₂O₂ exposure, as evidenced by reduced crystal violet staining intensity and diminished carbohydrate content within the EPS fraction.

This finding is consistent with previous reports indicating that oxidative stress can interfere with biofilm regulatory pathways,24 including quorum sensing and cyclic di-GMP signaling, both of which play central roles in biofilm matrix production and maintenance.25 It is plausible that H2O2 alters redox-sensitive regulatory networks in K. pneumoniae, leading to the downregulation of matrix-associated genes such as mrkA (fimbriae-related), wza (capsular polysaccharide export) and other genes involved in EPS biosynthesis.26

Previous studies have shown that sub-MICs of antibiotics such as rifampicin, ceftriaxone and ofloxacin can reduce biofilm formation, which is particularly relevant to the present study.19, 20, 21 However, other reports have indicated that sub-MIC levels of certain antibiotics may instead induce biofilm formation,27 highlighting the need for further investigation to clarify this phenomenon. While previous research has examined the bactericidal and anti-biofilm effects of H2O2 against various bacterial isolates,28, 29 no prior studies have specifically investigated the impact of sub-MIC levels of H2O2 on the antibiotic susceptibility of pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, the present study fills an important knowledge gap in this critical area of research.

The disruption of the solidity and integrity of the biofilm polymer matrix facilitates antibiotic penetration through the bacterial membrane, ultimately increasing antibiotic efficacy. Under normal conditions, the polysaccharide meshwork of the biofilm can markedly hinder the diffusion of β-lactam antibiotics such as cefotaxime, thereby reducing their local concentration and allowing bacteria embedded in deeper biofilm layers to survive.30

However, when the biofilm polymer matrix is weakened by H2O2 pretreatment, a marked increase in antibiotic susceptibility can be observed, as evidenced by reduced viable cell counts and enhanced killing kinetics.31 This mechanism may help restore the bactericidal activity of cefotaxime.31 Importantly, these findings do not reflect a direct synergistic interaction between hydrogen peroxide and cefotaxime in planktonic cells, but rather a biofilm-specific phenomenon, further confirming the critical role of the biofilm polymer matrix in antibiotic tolerance. This observation aligns well with the results obtained in the present study.

The present study also supports the hypothesis that the biofilm polymer matrix plays an active role in the dynamic and metabolic response of K. pneumoniae to environmental stress, such as exposure to H2O2. Thus, sub-MICs of H2O2 may trigger oxidative stress responses that redirect bacterial energy and resources from polysaccharide synthesis toward essential survival processes, including macromolecular repair pathways.32 This shift reduces the production of the biofilm polymer matrix, thereby increasing bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics.

Thus, the present study supports an innovative strategy for the treatment of wound infections caused by broad-spectrum resistant bacteria through the use of anti-biofilm agents, such as enzymes or oxidative compounds like H2O2 (at low concentrations). This approach offers a complementary therapeutic avenue by weakening the protective biofilm barrier and enabling existing antibiotics to act more effectively. However, it is important to note that the clinical application of H2O2 should be approached with caution, given its potential cytotoxic effects at higher concentrations.

While sub-MICs of H2O2 were effective in vitro, their in vivo application must take into account host tissue compatibility, potential cytotoxicity and the risk of selecting for bacterial strains resistant to oxidative stress, as multiple physiological mechanisms may interfere with antimicrobial efficacy.33 In the present study, the concentrations of H2O2 used ranged from ½ to 1/64 MIC, corresponding to 0.023% to 0.000719%. According to previous reports, these concentrations are considered safe for topical use, as studies have demonstrated that 0.5% H2O2 can be safely applied to the skin,34 and others have shown that 0.3%, 1% and even 3% H2O2 solutions are safe when used topically.35, 36, 37

Several nanotechnology-based delivery systems, such as H2O2-loaded nanocarriers, have been developed to enable controlled release and reduce toxicity, thereby making H₂O₂ safer for in vivo applications.38 Based on the present findings, it can be proposed that low concentrations of H2O2 be used in combination with antibiotics such as cefotaxime for the topical treatment of wound infections (e.g., skin injuries), rather than for systemic in vivo administration, due to potential toxicity-related complications. However, further research is required to validate this approach and assess its clinical efficacy and safety.

Limitations of the study

The present data focused on enhancing cefotaxime efficacy against a single clinical isolate of K. pneumoniae. The wider perspective may be developed in further studies, including investigations of multiple isolates, additional antibiotics and in vivo models to assess clinical applicability. Thus, the data present our perspective on sub-MIC H₂O₂ effects; however, in the future, the interactions between oxidative stress, biofilm dynamics and antibiotic efficacy may be studied and analyzed in more detail.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that sub-MICs of H₂O₂ effectively disrupt the biofilm polymer matrix of K. pneumoniae by inducing pore formation within the biofilm structure. These concentrations significantly enhanced the efficacy of cefotaxime by reducing its MIC values. The findings underscore the critical role of the biofilm matrix in antibiotic tolerance and support the concept of combining matrix-targeting agents with conventional antibiotics as a promising therapeutic strategy against biofilm-associated infections. By weakening the physical barrier of the biofilm, it may be possible to overcome one of the major challenges in the treatment of persistent bacterial infections.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.