Abstract

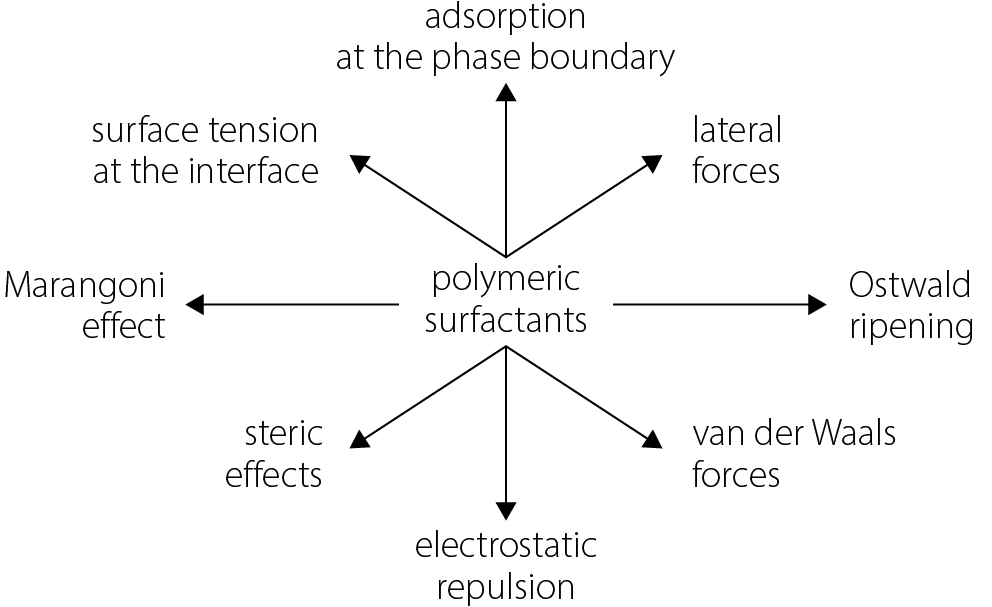

Polymeric surfactants play an important role in the research and development of drugs applied topically to the skin and mucous membranes. Their versatile properties include the ability to lower surface tension, thereby favorably contributing to the energetic balance of the emulsification process during the preparation of various dosage forms. In addition, they offer important structural advantages that enhance the stability of the resulting pharmaceutical or cosmetic products through electrostatic repulsion and steric effects. The influence of viscosity and density should also be taken into account when polymeric surfactants are considered as additives, as these are crucial components of various drug formulations. Emulsions used in ointments and creams are among the most relevant dosage forms affected by surface and interfacial tension phenomena. However, other dosage forms also require the use of surfactants, which may belong to the group of polymeric compounds.

Streszczenie

Polimerowe surfaktanty odgrywają ważną rolę w badaniach i rozwoju leków stosowanych miejscowo na skórę i błony śluzowe. Ich wszechstronne właściwości obejmują obniżanie napięcia powierzchniowego, a tym samym korzystnie wpływają na równowagę energetyczną procesu emulsyfikacji podczas przygotowywania różnych form leków. Z drugiej strony polimerowe surfaktanty posiadają ważne i cenne zalety strukturalne, które zwiększają stabilność otrzymanego produktu farmaceutycznego lub kosmetycznego poprzez odpychanie elektrostatyczne, a także efekty steryczne. Należy również wziąć pod uwagę wpływ lepkości i gęstości, gdyż polimerowe surfaktanty są uważane za dodatki, które są kluczowymi składnikami różnych form leków. Emulsje stosowane jako maści i kremy są najbardziej interesującymi formami leków, na które może wpływać zjawiska napięcia granicznego powierzchni. Jednak również inne formy leków wymagają stosowania surfaktantów, które mogą pochodzić z grupy polimerów.

Key words: surface tension, van der Waals forces, polymeric surfactants, steric effect, electrostatic repulsion

Słowa kluczowe: napięcie powierzchniowe, surfaktanty polimerowe, efekt steryczny, odpychanie elektrostatyczne, siły van der Waalsa

Introduction: General remarks on surfactants

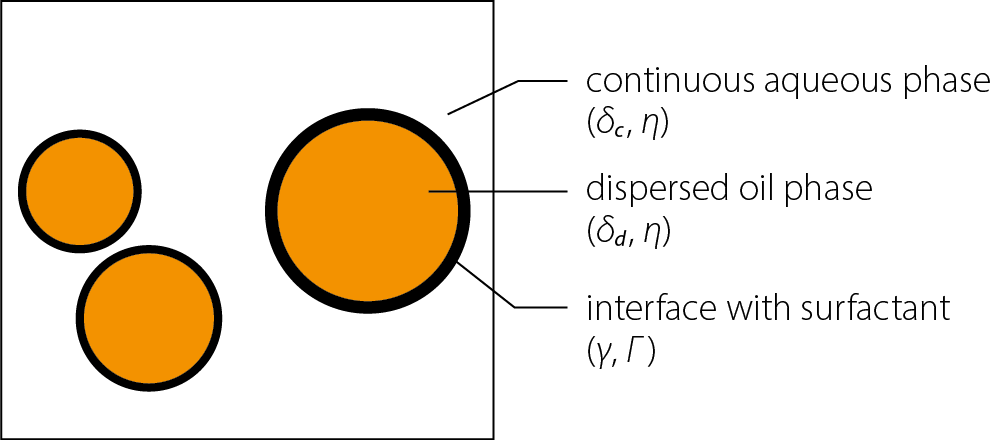

The skin is a complex, predominantly lipophilic barrier to substances with prophylactic and therapeutic effects. Moreover, when targeting the deeper layers of the skin or subcutaneous tissue, the thickness and diffusion resistance of the hydrophilic layers also play an important role. Therefore, surfactants, by reducing surface tension at interfaces, can positively influence both the skin–blood barrier and the ointment base–skin interface. As chemical compounds that lower surface tension, surfactants play a crucial role in the formulation of numerous drug products, particularly those in which the modification of surface tension at the phase boundary is a key factor. A good example of such formulations are emulsions (Figure 1), in which reducing surface tension at the phase boundary decreases the energy required to achieve the desired level of dispersion. Lowering surface tension is also important for maintaining the emulsion as a stable dispersion over time and for ensuring a favorable re-dispersion profile when low energy is applied – e.g., by simply shaking the container before use. The essence of the functional definition of surfactants lies in their ability to reduce surface tension – a property first observed and applied in research by early 20th-century scientists such as Szyszkowski and Langmuir, building upon Gibbs’

foundational work.1, 2, 3

Objectives

In this review, the authors aim to present the fundamental mechanisms and examples of the application of polymeric surfactants as components of pharmaceutical and cosmetic preparations intended for topical use on the skin. Selected equations that may facilitate understanding of formulation processes and the stability of pharmaceutical emulsions are also included.

Mechanisms of action of surfactants

A surfactant, by positioning itself at the interface between 2 phases, hydrophilic and hydrophobic, reduces the cohesive forces between the molecules of these phases and lowers the energy required to disperse one phase within the other. The orientation of the corresponding structural groups of the amphiphilic surfactant molecule within the hydrophilic or hydrophobic phase also serves to stabilize the droplets of the dispersed phase.

Both electrostatic effects, arising from the electric charges of the surfactant’s functional groups, and steric effects, resulting from the spatial arrangement of these groups within the dispersed and dispersing phases, contribute to this stabilization. The mechanisms through which surfactants interact to stabilize emulsions are schematically illustrated in Figure 2.

A key aspect in considering systems containing surfactants at interfaces is the relationship between surface tension and the degree of surfactant coverage at the interface.4, 5 Within an emulsion droplet, there is a certain pressure, called capillary pressure, described by the Laplace equation, in which the pressure difference between the interior of the emulsion droplet and the continuous phase (ΔP) depends on the surface tension (γ) and the radius of the dispersed particle (r). A decrease in surface tension positively influences the size of the formed emulsion droplets (Eq. (1)).

The illustrative equation (Eq. (2)) demonstrates the effect of reducing the surface tension (γ) on the surface area (A) obtained using a specific energy input (E) to produce an emulsion.6, 7

Eq. (2)

However, surfactants with a macromolecular structure can also interact with the environment through polymer chains anchored in the dispersed phase. It is easy to infer that the structure of these chains, along with their size and amphiphilic properties, can significantly influence the stability of the resulting emulsions. In the simplest terms, this occurs through their effect on parameters such as particle radius (r), medium viscosity (η), and the densities of the continuous and dispersed phases (ϱ_c, ϱ_d), as described by Stokes’ equation, which defines the sedimentation velocity (u) of dispersed particles under gravitational acceleration (g), as shown in Eq. (3).8

Eq. (3)

Other factors also influence the stability of these dispersions, as described by the Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO) theory.9, 10 Furthermore, 2 well-known phenomena – the Ostwald effect and the Marangoni effect – also impact the stability of pharmaceutical emulsions, including those intended for topical application.11, 12, 13, 14

The Ostwald effect involves the growth of larger emulsion droplets at the expense of smaller surrounding droplets. In this phenomenon (Eq. (4)), the basic relationship between the radius of particles dispersed over time (r(t)) and the initial radius (r(o)), as described by Lifshitz and Slyozov for solid particles, depends on the surface tension (γ), the solubility of the dispersed particle material (css), its molar volume (Vm), and the diffusion coefficient (D), with the universal gas constant (R) and absolute temperature (T) appearing in the equation.15

Eq. (4)

The Marangoni effect can contribute to emulsion stabilization; however, an inappropriately selected surfactant or changes in temperature can alter the Marangoni force, as described in Eq. 5 (FM). This force arises from local differences in concentration (dC) and temperature (dT) across different regions (dx) of the stabilized emulsion particle surface.16 The resulting flow of the surrounding medium between emulsion particles influences the tendency of opposing surfaces to aggregate.

Eq. (5)

Adsorption at the phase boundary

In studies of adsorbate adsorption on an adsorbent, a key concept is the degree of interfacial surface coverage by the adsorbate (θ). By lowering surface tension, the surfactant accumulates at the interface. This process is interpreted as adsorption and is described by Eq. (6), which introduces the concepts of surface excess (Γ) and maximum surface excess (Γ_∞). The ratio of these 2 quantities represents the degree of surfactant coverage at the phase boundary.

Eq. (6)

In isotherm equations and the corresponding surface tension equations, the concept of the minimum surface area per molecule – or per mole of molecules – accumulated at the surface (ω) is often used instead of the maximum surface excess. The latter is therefore the inverse of the maximum surface excess.17 Adsorption at the interface can be described by the Gibbs isotherm (Eq. (7)), which relates the surfactant concentration (C) to the surface tension of the solution (γ) and the surface excess (Γ).

Eq. (7)

In the case of the Langmuir isotherm (Eq. (8)), the surface excess equation takes a slightly different form, incorporating a characteristic adsorption constant of the surfactant at the interface (K).

Eq. (8)

In some cases, strong lateral interactions affect the behavior described by the previously mentioned equations. The Frumkin isotherm (Eq. (9)) accounts for the influence of these interactions, represented by the lateral interaction coefficient (a).18, 19

Eq. (9)

The influence of surfactants on surface tension at the phase boundary

With surfactant adsorption at the interface, the interactions between solvent molecules at the solution surface are reduced, resulting in a decrease in surface tension. In studies using a Langmuir balance, authors often employ Eq. (10) for the equilibrium surface pressure (Π), defined as the difference between the surface tension of the pure solvent (γ0) and that of the solution (γ).20, 21

Eq. (10)

When lateral interactions are taken into account, the Frumkin isotherm (Eq. (11)) yields the corresponding expression for surface pressure.22

Eq. (11)

Surface tension is explicitly expressed in the Gibbs isotherm equation. Other equations, such as the Langmuir and Frumkin isotherms, use the relationship described by the Gibbs isotherm, allowing surface tension to be determined from these respective models. The Szyszkowski equation (Eq. (12)), derived from the Langmuir isotherm, is among the most widely used in studies examining the effects of various substances on the surface tension of their solutions. It includes system-specific constants (a, b), which can be further interpreted.23, 24, 25

Eq. (12)

By expanding the equation to include the adsorption constant (K), surfactant concentration (C) and saturated surface excess (Γs) (Eq. (13)), a slightly modified but practically useful form is obtained.26

Eq. (13)

A modification of this equation, sometimes presented alongside the concept of the Langmuir–Szyszkowski distribution coefficient (Eq. (14)), can be used to examine changes in surface pressure (Πt) in relation to variations in surface excess over time (Γt).27

Eq. (14)

Determining surface tension according to the Frumkin isotherm requires using an equation that incorporates lateral interactions between surfactant molecules, represented by the coefficient (A). Similar to the Szyszkowski equation, Eq. (15) also includes system-specific constants (af and bf).28

Eq. (15)

In mathematical modeling of interfacial phenomena, the effect of surfactant concentration on surface tension reduction is analyzed, allowing prediction of the formation and stabilization of emulsion-type dispersions.29 In both the Gibbs isotherm (Eq. (7)) and the Szyszkowski equation, derived from the Langmuir isotherm (Eq. (13)), the term n appears in the expressions.

This term represents the number of species contributing to surface activity, which may arise from dissociation, even though the Langmuir isotherm describes a monolayer.30, 31 The equation linking the Langmuir isotherm to changes in surface tension, as described above, is sometimes referred to as the Langmuir–Szyszkowski equation (Eq. (13)).32 In cases where adsorption and surface tension changes involve multicomponent mixtures, the Butler equation – a modification of the Szyszkowski equation – can be applied.33

The influence of surfactants on the interactions between emulsion particles

According to the generally accepted theory developed in the 2nd half of the 20th century, particles of the dispersed phase are subject to mutual interactions that depend on various factors. These interactions can lead to particle approach, aggregation and flocculation, which may ultimately result in the breakdown of the system, such as emulsion separation or suspension sedimentation.34 This theory has broader applications, as it can also be used to describe interactions not only among inanimate particles but also in the context of microorganisms.35

The general consideration of particle interactions (Eq. (16)) includes the van der Waals attractive energy (Ea), repulsive energy due to the electric double layer (Er) and steric repulsion (Es).

Eq. (16)

Emulsion particles attract one another, with van der Waals forces playing the primary role in these interactions. These forces include dispersion forces – namely, London forces, dipole–dipole forces and induced dipole–dipole forces. According to the DLVO theory, the energy of these interactions governs the approach of emulsion droplets, which can ultimately lead to system destabilization. The van der Waals attractive energy (Ea) is approximately proportional to the square of the number of molecules packed into 1 cm3 of the system (q) and the mutual interaction energy of 2 such molecules separated by 1 cm in vacuum (β), expressed as the Hamaker–London constant (A), as described in Eq. (17). The separation distance in the denominator (H) represents the difference between the distance between the centers of 2 emulsion particles (R) and twice the particle radius (a).36

Eq. (17)

The subsequent terms of the equation provide information on factors contributing to the stability of the dispersed system. An approximate solution of the equation (Eq. (18)) – for the electrostatic repulsion energy of the electric double layer according to the Debye–Hückel approximation (Er) for spherical particles – describes the influence of the continuous phase properties, including its permittivity in the medium (ε) and in vacuum (ε0), the ionic strength represented by the inverse Debye length (κ) and the electric potential at the surface of the emulsion particles (Ψ0). This formulation allows estimation of the influence of the surface potential, in particular, on the stability of a liquid dispersion.37

Eq. (18)

In addition to the attraction resulting from van der Waals forces (Ea) and electrostatic repulsion (Er), the stability of the dispersion system is also influenced by the steric factor (Es), which arises from the spatial configuration of the surface of a dispersed particle within a specific dispersing phase. This factor is sometimes interpreted as the enthalpic stabilization term (ΔG).

The approximate formula for this term (Eq. (19)) determines the repulsive potential based on the concentration of adsorbed surfactant in the adsorbed layer (C), the volume fraction of the solvent (v1), the density of the adsorbed material (ρ), the entropic factor (ψ), the enthalpic factor (χ), the thickness of the adsorbed layer (δ), the distance between the surfaces of emulsion particles (H0), and the radius of the dispersed particles (a).38, 39

Eq. (19)

According to Lazaridis et al. (Eq. (20)), steric repulsion (Es) should be interpreted as the sum of terms arising from entropy changes due to the configuration of polymer chains – also referred to as volumetric confinement (EVR) – and from the enthalpy changes of overlapping polymer surfactant regions, which contribute to system stabilization (EH).40 This energy is related to the enthalpy of mixing, i.e., the mutual interactions of polymer chains stabilizing the dispersed particles.

The 1st term, entropic in nature, is based on the cross-sectional area of the interacting layer between 2 particles (Si), the fraction of interface coverage by surfactant (θ), the number of adsorbed molecules per unit area (Ns), the length of polymer chains (δ), and the distance between particle surfaces (h). It is further corrected by the ratio of the volume fraction of the adsorbed surfactant (ϕ) to the high-density fraction occurring at the contact point of the polymer shells (ϕ*), multiplied by Boltzmann’s constant (kB).

The 2nd term, enthalpic, is based on the volume of the interacting layer between 2 particles (Vi), the surfactant weight concentration in the adsorbed layer (Ci), and a coefficient derived from Flory and Krigbaum theory (B). This term is also adjusted to account for the relevant volume fractions of the adsorbed surfactant (ϕ, ϕ*).

Eq. (20)

In addition, the energy associated with elastic repulsive forces (Ee) and the energy resulting from the dissolution of surfactant molecules in the continuous and dispersed phases (Ed), which leads to differences in osmotic pressure, are also distinguished.41 The formula for the energy of elastic repulsive forces (Ee), described as Eq. (21), takes into account parameters such as the minimum distance between particles (h0), the contour length of polymer chains surrounding the stabilized emulsion particle (i.e., the thickness of the stabilizing barrier, le), the total number of attached chains per unit area (ν), and the radius of a spherical particle (r).42

Eq. (21)

The influence of osmotic pressure on the repulsive potential can be expressed, i.a., by Eq. (22), in which the osmotic pressure between the surfaces of macromolecules (Π) increases to a maximum value (Π0). This pressure depends on the ratio of the distance between the surfaces (h) to the minimum separation distance (λ), which may be determined, e.g., by the gyration radius.43

Eq. (22)

General overview of polymeric surfactants

Among amphiphilic chemical compounds used in pharmaceutical formulations, macromolecular compounds – polymers containing both hydrophilic and lipophilic components – deserve special attention. The combination of amphiphilic properties with features inherent to the macromolecular structure significantly enhances their potential applications in semi-solid drug forms, such as ointments, creams and hydrophilic gels. Numerous methods exist for the systematic classification of polymers affecting surface tension. One approach considers the structure of the polymer chain, including the arrangement of interwoven hydrophilic and lipophilic segments and the presence or absence of branching in the main linear chain. Table 144, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 presents an example of the systematic classification of polymeric surfactants.

One of the oldest and most widely used groups of polymers influencing phase-boundary properties in dispersed systems are amphiphilic polymers – homopolymers and copolymers obtained through random polymerization. These polymers are characterized by the random distribution of hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups.69 Among them, nonionic polymers can form weak micelles but primarily adsorb at interfaces. Adsorption at the interface alters the interactions between molecules in both phases. These polymers find applications in cosmetics as hydrophilic coatings and emulsion stabilizers.70

Ionic polymers of this type contain hydrophilic ionic groups, such as carboxyl or sulfonic groups, along with corresponding randomly distributed hydrophobic segments. In the presence of oppositely charged ions or other surfactants, these polymers can form aggregates. They reduce surface tension through electrostatic interactions and are used as thickening agents, emulsion stabilizers and drug carriers, e.g., to control the release of active substances from formulations.71

Amphiphilic block copolymers are a particularly interesting and widely used class of polymers.72 In these polymers, hydrophilic and hydrophobic segments are systematically arranged in blocks, with a defined content of mer units in each segment, as illustrated by poloxamers. Block copolymers form micelles in aqueous solutions and stabilize oil-in-water emulsions by forming a hydrophobic core surrounded by a hydrophilic shell. Their applications include drug carriers, bases for dermatological and cosmetic creams and gels, solubilizers, and stabilizers of emulsions and foams.

Polymers with comb-like side chains possess characteristic long hydrophobic side chains that adsorb at interfaces and reduce surface tension. These polymers stabilize emulsions in practice via steric effects and surface tension reduction.73

Advances in polymer synthesis have enabled the production of hyperbranched and dendrimeric polymer surfactants.74, 75 These macromolecules form aggregates and encapsulate hydrophobic molecules within a three-dimensional branched structure, facilitating the solubilization of hydrophobic substances. A hydrophobic, nonpolar molecule is surrounded by branched hydrophobic fragments of the macromolecule, allowing the creation of diverse nanostructures and drug carriers, and effective solubilization of hydrophobic compounds.

Selected examples of polymeric surfactants

The use of an appropriate surfactant or surfactant mixture is particularly important for the efficacy of topically administered drugs and has been the subject of detailed research for many years.76 Table 277, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96 presents examples of applications of polymeric surfactants in selected formulations with therapeutic, prophylactic or cosmetic effects.

Among polymeric emulsifiers commonly used in topical preparations, poloxamer 407 and poloxamer 188 are noteworthy. Poloxamer 407 is a block copolymer consisting of 3 sequential blocks – hydrophilic, lipophilic and hydrophilic – with the hydrophilic blocks composed of 101 mer units and the lipophilic block containing 56 mer units. Its molar mass is approx. 12,600 g/mol. Poloxamer 188 contains 75, 30 and 75 corresponding mer units in its hydrophilic–lipophilic–hydrophilic blocks, with a molar mass of approx. 8,400 g/mol.

Alternatives to conventional block copolymers containing oxyethylene and oxypropylene groups include polymers with sequences based on polyoxybutylene, polyoxyethylene and polyoxybutylene units, proposed for applications such as anticancer drug carriers.97, 98 As shown in Table 2, many applications of polymeric surfactants involve the production of emulsions or nanoemulsions.

The potential of PEG-400 as a co-surfactant in microemulsions for drug delivery was evaluated using carvedilol as a model compound. The authors suggest that such systems may be applied to enhance various drug delivery routes.99 Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) has also been successfully used in systems requiring surface tension reduction, such as self-emulsifying systems for enhanced delivery of cyclosporine A.100

Poloxamers and poloxamine surfactants are frequently considered suitable for designing transdermal drug delivery systems, with their activity appearing to be reversible – an important advantage over traditional surfactants, which may irreversibly alter the structure of the skin layers.101 Among polysiloxane surfactants, solvation activity has been exploited, with nystatin used as a model drug to demonstrate the beneficial effects of these polymeric surfactants.102

Polymeric surfactants also play a significant role in cosmetic science, improving the design of numerous cosmeceutical products through film formation, modification of viscous properties, thickening, and stabilization or destabilization of foams.103 Another notable application of polymeric surfactants is the stabilization of liposomal structures. They can be applied as ready-to-use materials or may undergo polymerization during the application process.104, 105

Limitations of the study

Polymeric surfactants are widely used in dermatological drug formulations, but their impact on rheology cannot be neglected. Both the impact on rheological parameters and the chemical nature of their functional groups in selected cases can complicate their use in topically administered drug formulations. In the case rheological complications, an unfavorable increase or decrease in the formulation’s viscosity cannot be ruled out, even during use. On the other hand, surfactant functional groups can interact physically or chemically with their counterparts in the molecules of other excipients, as well as in the molecules of the drug. Consequently, in some cases, a modification of the biological activity of the formulation can be expected. The limitations mentioned above are eliminated through careful analysis and selection of formulation components, as well as proper technological procedures.

Conclusions

The production of nanostructures, nanoparticles and nanospheres represents another important area of application for polymeric surfactants. Many researchers emphasize their potential to form specific aggregates that can function as independent drug delivery systems. In addition, polymeric surfactants are used in advanced formulations such as films, foams, multiple emulsions, and hydrogels. In some cases, their primary role lies in the ability to create a stable solution, a micellar drug solution or a complex of various substances.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.