Abstract

Due to physiological and anatomical barriers, optometrists and drug delivery specialists have long faced challenges in administering medications to the eyes. These ocular barriers – both permanent and temporary – limit the entry of foreign substances and reduce the effective absorption of therapeutic agents. Polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) provide advantages such as selective tissue targeting, improved drug bioavailability, stability, and controlled drug release. Their ability to overcome barriers like the precorneal film, cornea and intra-retinal regions depends on properties such as interfacial ligands, mucoadhesion, hydrophobicity, particle size, and surface charge. Careful design tailored to specific ocular tissues and diseases is essential. This study aims to explore the potential applications of polymeric NPs across various pharmaceutical categories in the treatment of ocular conditions.

Key words: stability, polymeric nanoparticles, ophthalmic application, challenges for vision

Introduction

Due to its complex anatomy and strong defense mechanisms against external substances, including therapeutic agents, the eye presents a significant challenge in drug delivery and medical treatment. While traditional topical formulations are commonly used for the anterior segment of the eye, the majority of the drug dose is lost due to ocular defense mechanisms. To improve drug retention, efforts have been made to minimize local and systemic side effects while enhancing therapeutic efficacy. For diseases affecting the posterior segment of the eye, intravitreal therapy or systemic administration of intravitreal implants and injections is often required. Developing ocular drug delivery methods that enhance therapeutic efficacy and enable targeted tissue absorption is essential. Since the cornea and conjunctiva are sensitive to penetration enhancers, careful selection of such agents and the design of compatible drug formulations are critical components of an effective delivery strategy.1

According to their intended purpose, nanoparticles (NPs) might or might not contain a therapeutic molecule. Drugs can be dissolved, adsorbed, entrapped, or chemically linked within nanoscale frameworks, resulting in various structures such as NPs, nanospheres or nanocapsules. All these terms share a common feature: they refer to NPs that encapsulate or carry drugs. Polymeric NPs offer remarkable flexibility as a drug delivery technology due to their ability to deliver medication to specific tissues or intracellular compartments by overcoming physiological barriers through both passive and ligand-mediated targeting mechanisms. When properly formulated, polymeric NPs require less frequent administration, exhibit prolonged retention in the extraocular area and can be as easy to use as topical solutions, while offering the added benefit of improved patient compliance.2–4 To improve drug delivery and reduce harmful side effects, NPs have been extensively studied for their ability to carry a wide range of both small and large molecular entities, including drugs, peptides, amino acids, vaccines, and genetic material. Two fundamental requirements for polymeric NPs are that the polymers used in their fabrication must be both biocompatible and biodegradable, as the NPs remain within target cells and circulate for extended periods. A variety of polymers meeting these criteria have been employed, and evaluating their suitability, based on the resulting NP properties, represents a compelling area of research in the development of an optimal therapeutic platform for the treatment of various ocular conditions.5

Anatomy of the eye

The human eye is an extremely complex and delicate organ, composed of both anterior and posterior segments. The anterior segment includes the tear film, cornea, aqueous humor, pupil, lens, and ciliary body. The posterior segment consists of the vitreous humor, retina, optic nerve, and supporting structures. It should be noted that some elements, such as the conjunctiva and cornea, span both regions and play key roles in ocular protection and vision. The volume and composition of the tear film are regulated by the orbital glands and epithelial secretions. The cornea plays a crucial role in focusing light entering the visual field. It is composed of 3 distinct layers: the epithelium, stroma and endothelium. The corneal epithelium consists of 4–7 layers. The stroma is a dense layer composed primarily of water. The epithelium plays an important role in maintaining corneal transparency. The pigmented part of the eye is called the iris and it regulates the amount of light that enters the eye and reaches the retina. The structure of the ciliary body consists of ciliary muscles, stroma and both pigmented and non-pigmented epithelial layers.6 Interaction between the anterior and posterior segments of the eye is facilitated by the capillary network within the ciliary body. The vitreous humor is a transparent, gel-like connective tissue located between the retina and the lens. It contains no blood vessels and is composed primarily of water (99.9%), along with hyaluronic acid (HA), collagen and electrolytes.7 Conjunctiva is the fragile, translucent membrane covering the surface of the eye. The eyelids protect the anterior part of the sclera. The choroid is a vascular membrane located between the sclera and the retina. The retina is an extremely delicate structure composed of glial and neural tissues. It generates electric impulses, which are transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve.8–12

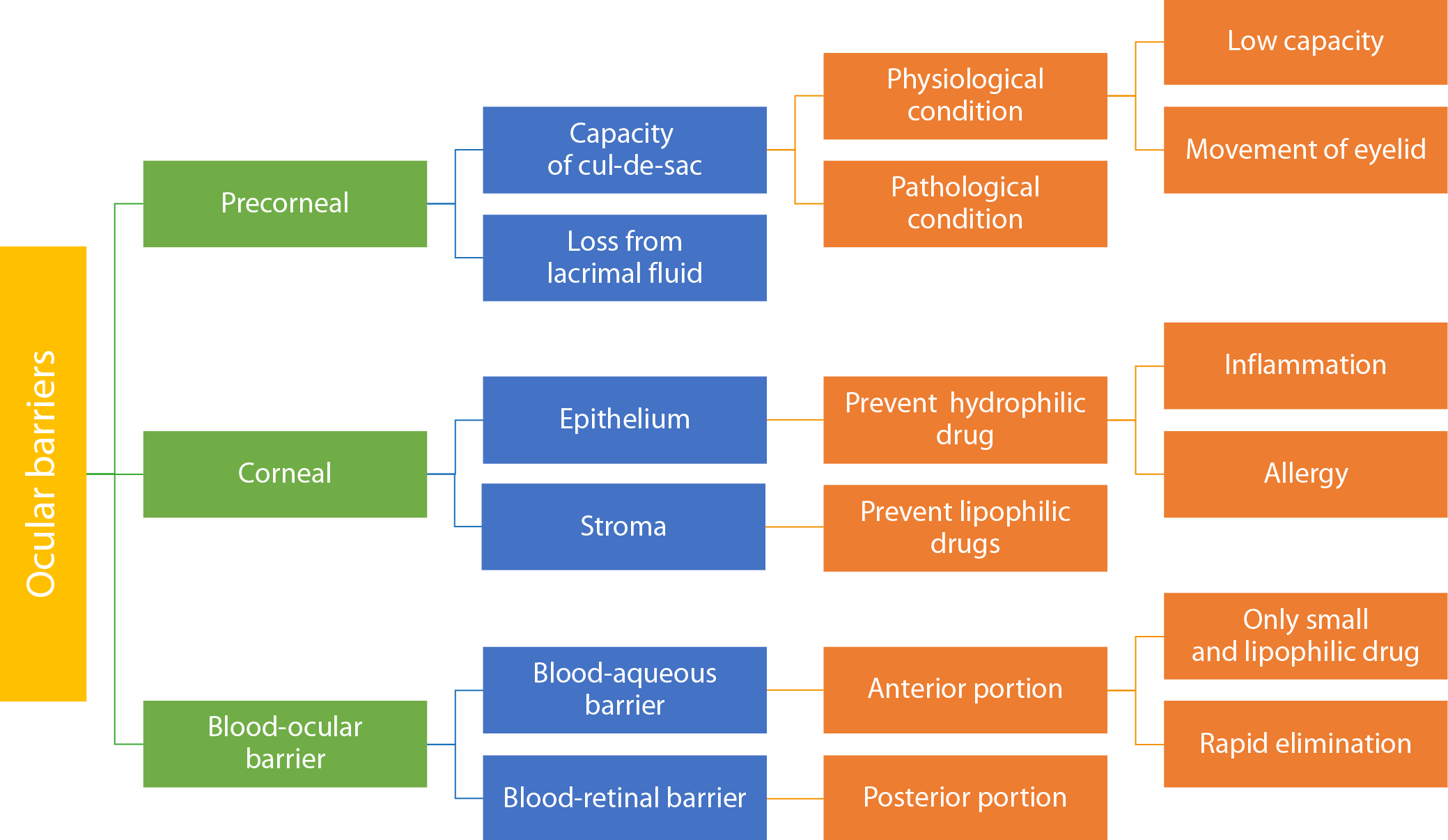

Barriers to ocular drug delivery

Ocular drug delivery is difficult due to various barriers that limit drug efficacy and absorption. These barriers include anatomical, physiological and metabolic factors.

Pre-corneal barriers

Capacity of the cul-de-sac

The human eye’s conjunctival cul-de-sac is a small anatomical space with an approximate volume of 20–30 μL. It is formed where the bulbar and palpebral conjunctivae meet, including a deeper depression beneath the upper eyelid. When the lower eyelid returns to its normal position, the capacity of this space is reduced by approx. 70–80%.13 Inflammation and allergic reactions of the eye can further reduce the capacity of the conjunctival cul-de-sac. Since a drug’s residence time and concentration are closely correlated with its therapeutic efficacy, the limited capacity of the cul-de-sac may lead to a decrease in intraocular drug concentration, ultimately reducing the treatment’s effectiveness (Figure 1).

Drug loss in lacrimal fluid

The management of ocular fluid drainage is one of the key challenges in the precorneal area. Drug loss from the lacrimal fluid can occur due to non-productive absorption through the conjunctiva, excessive lacrimation and nasolacrimal drainage. In addition, protein binding and metabolic processes within the ocular environment may further hinder drug uptake and reduce therapeutic efficacy.14 The continuous replenishment of lacrimal fluid plays a vital role in keeping the eyes hydrated and protecting them from dust or pathogens that could reach deeper ocular structures. To ensure therapeutic efficacy, it is essential to prolong the residence time of the administered formulation. Various strategies can be employed to enhance retention time on the ocular surface.15

Corneal barriers

The cornea functions as a robust barrier, protecting the eye from various physiological and chemical insults. While the lens plays a key role in focusing light and filtering ultraviolet (UV) radiation, it is not involved in barrier functions at the ocular surface. It also plays a crucial role in focusing light onto the retina. The lens is composed of 3 parts: epithelium, stroma (cortex) and endothelium. The epithelium consists of tightly packed cells arranged in 5–7 layers. The stroma is a dense layer composed primarily of water. Lipophilic drugs penetrate more readily through the corneal epithelium, while hydrophilic drugs diffuse more efficiently through the stroma. The endothelium plays a key role in maintaining corneal transparency and facilitates the selective entry of hydrophilic drugs and macromolecules into the aqueous humor. Drug molecular weight, charge, degree of ionization, and hydrophobicity significantly influence corneal penetration. These factors collectively determine the rate-limiting step in the passage of drugs from the lacrimal fluid into the aqueous humor.16

Blood–retinal barriers

These barriers prevent foreign pathogens from entering the bloodstream. They are classified into 2 main types: blood–retinal barrier (BRB) and blood–aqueous barrier (BAB). The BAB, located in the anterior segment of the eye, restricts the entry of various substances into the intraocular environment. The BRB facilitates the passage of small, hydrophobic drugs. The clearance of medications from the anterior segment occurs more rapidly for such compounds than for larger, hydrophilic molecules. The BRB is located in the posterior segment of the eye and is formed by pigmented epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells of the retina. It prevents from the entry of harmful substances, water and plasma components into

the retinal tissue.17

Ocular diseases

Over 1 billion people worldwide suffer from vision impairment, with 36 million being blind. Anatomical barriers and frequent intravitreal injections make ocular drug delivery complex. Other factors, such as the need for intravitreal injections, further impede effective medication delivery to the inner structures of the eye. Therefore, addressing these challenges is crucial for effective treatment.18 A promising strategy to enhance intraocular drug distribution involves the use of polymeric NPs with tailored surface properties and variable diameters, enabling targeted delivery to specific ocular tissues. These NPs may offer controlled release profiles, reducing the frequency of drug administration required.19

Glaucoma

Glaucoma, characterized by progressive vision loss, is the 2nd leading cause of blindness worldwide after cataracts. It is estimated that by 2040, the global number of glaucoma patients may reach 111.8 million. A key feature of glaucoma is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP).20 Given that glaucoma is a complex disease, the primary goal of current treatment is to slow or prevent further vision loss caused by IOP.21 In glaucoma management, brimonidine tartrate-loaded chitosan NPs, formulated using sodium tripolyphosphate, may help reduce dosing frequency and provide sustained drug release.22 For the treatment of glaucoma, researchers developed HA-enhanced chitosan NPs loaded with hydroxychloroquine (DH) and timolol maleate (TM). Hyaluronic acid improves mucoadhesion, allowing the NPs to deliver the drugs locally and in a sustained manner to ocular tissues. The chitosan–HA NPs demonstrated a significant reduction in IOP, suggesting that HA may enhance both the efficacy and mucoadhesive properties of chitosan NPs.23 Radwan et al. suggested that chitosan-coated bovine serum albumin NPs (CS-BSA-NPs) may serve as an effective platform for the topical delivery of tetrandrine (TET) in the treatment of glaucoma.24 Shahab et al. aimed to develop chitosan-coated polycaprolactone (PCL) NPs loaded with dorzolamide to enhance ocular drug delivery. The NPs are optimized using a single-step emulsification method, guided by a 3-factor, 3-level Box–Behnken design. The optimized dorzolamide-loaded chitosan NPs showed a strong correlation between independent and dependent response variables. They exhibited biphasic release behavior and showed a 3.7-fold increase in mucoadhesion compared to the control formulation. Additionally, the NPs were found to be non-irritating and safe for ocular administration, indicating their safety and potential to enhance therapeutic efficacy.25 Dubey et al. developed brinzolamide nanocapsules for glaucoma prevention using chitosan–pectin polymers. These nanocapsules offer improved bioavailability and better corneal penetration compared to conventional eye drops.26 A recent study presented a safe, well-tolerated and neuroprotective topical formulation of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)–polyethylene glycol (PLGA–PEG) NPs loaded with memantine for glaucoma treatment. The formulation, containing 4 mg/mL of memantine, significantly reduced retinal ganglion cell damage in a murine model of ocular hypertension. Memantine-loaded NPs (MEM-NPs) were well tolerated in both in vivo and in vitro settings.27 Another study developed nanoparticulate systems (NCs) containing acetazolamide (AZM) aimed at reducing IOP. The formulations had high encapsulation efficiency. They improved drug permeation, reduced IOP significantly and provided prolonged therapeutic effects.28 Warsi et al. evaluated the encapsulation efficiency of dorzolamide-loaded PLGA NPs formulated with 2 different emulsifiers and vitamin E TPGS. The results showed that the NPs had high encapsulation efficiency, improved corneal permeability and were non-irritating. Additionally, drug concentration in ocular tissues was elevated. The formulation also showed therapeutic efficacy, with a significant reduction in IOP following a single topical administration.29

Uveitis

Autoimmune uveitis is an ocular disorder that affects the posterior segment of the eye. Studies have shown that NP-based drug delivery methods can offer more effective treatment with fewer adverse effects in managing immunological autoimmune uveitis.30 Research on posterior segment disorders has explored the use of intravitreal injections of PLGA NPs loaded with dexamethasone (DEX). These systems have demonstrated the ability to sustain therapeutic DEX concentrations over an extended period and distribute the drug throughout various ocular layers.31 Sakai et al. examined the therapeutic potential of betamethasone phosphate (BP) encapsulated in biocompatible and biodegradable NPs composed of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) homopolymers or PEG-block-PLA copolymers, referred to as stealth nanosteroids. This NP-based delivery system reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in the retinas of rats with experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) and significantly lowered their clinical scores. These findings suggest that NP-mediated delivery may represent a promising strategy for managing intraocular inflammation.32

Cataract

Cataracts are one of the leading causes of visual impairment worldwide, accounting for approx. 40–60% of global blindness according to the National Program for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment. A cataract is the opacification or progressive clouding of the ocular lens. Identified risk factors include prolonged exposure to UV radiation, diabetes, poor nutrition, genetic predisposition, and smoking.33 Pranoprofen (PF) is an effective anti-inflammatory agent commonly used in the management of blurred vision and during cataract surgery. The drug was formulated using PLGA NPs and evaluated for cytotoxicity, in vivo ocular penetration, ophthalmic tolerability, and anti-inflammatory efficacy. In vivo ocular penetration in New Zealand rabbits demonstrated comparable absorption levels across formulations, with PF-F2NPs showing the highest quantitative pupillometry (QP) value and a significant reduction in ocular edema. The PF-F1NPs formulation was well tolerated and non-irritating to ocular tissues, whereas PF-F2NPs exhibited higher Quick Response (QR) values (quantities of PF retained in the cornea) compared to other tested formulations.34

Fungal keratitis

Fungal keratitis is a serious ocular condition that primarily affects the cornea. It is caused by various fungal species, including Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, and Candida parapsilosis. Mycotic inflammation accounts for up to 40% of all cases of corneal inflammation in low-income countries.35 Risk factors for fungal keratitis include ocular conditions such as trauma, contact lens use, topical corticosteroid application, and previous corneal surgery, as well as systemic conditions like leprosy.36 Researchers developed voriconazole-loaded chitosan NPs using the ionic gelation method with sodium tripolyphosphate to establish an effective topical ocular delivery method. The NPs were characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). A Box–Behnken design was employed and the formulation showed high drug loading capacity, absence of a burst release effect and sustained drug release over 48 h, making it a promising strategy for ocular antifungal therapy.37

Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the leading causes of vision loss and blindness worldwide and represents a permanent complication of diabetes. In severe cases, patients may experience progressive symptoms such as floaters, blurred or distorted vision and partial or complete vision loss due to retinal detachment. Clinically, timely laser therapy can improve ocular circulation, prevent vitreous hemorrhage and inhibit the formation of abnormal retinal blood vessels. Additionally, intravitreal anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) injections are commonly required to reduce retinal inflammation and improve visual outcomes.38 Unfortunately, some individuals respond effectively to intravitreal injections and repeated delivery may destroy optical cells.39 Vitrectomy is commonly required in situations of vitreous hemorrhage or proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Many medications have poor ocular absorption, and the potential side effects or hazards associated with invasive treatments make there a rising need for novel drug delivery systems. These innovative techniques provide intriguing alternatives for the effective treatment of DR.40

Liu et al. investigated the effects of an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab-chitosan NPs on the expression of VEGF messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and VEGF protein inside diabetic rat’s corneas. The findings showed that bevacizumab could be continuously released from chitosan NPs and that this replacement was efficient in preventing choroidal neovascularization.41 Furthermore, the anti-VEGF agent-containing NPs significantly reduced VEGF expression and had a long-lasting effect. Triamcinolone acetonide-loaded NPs were used in a mouse study for DR, with a PCL core and a hydrophilic poloxamer 188 shells made from PLGA and chitosan NPs.42 Interleukin 12-encapsulated cytokines have been shown to prevent angiogenic tumors. Despite a moderate encapsulation efficiency of 34.7%, the formulation demonstrated prolonged drug release as well as a greater ability to reduce VEGF-A and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) production in mouse endothelial cells and DR mouse cornea. Increased retinal thickness and decreased new blood vessels following therapy show that the specific dosage significantly reduced retinal loss in DR rats.43

Age-related macular degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) was the leading cause of visual loss in developed countries. People over the age of 50 are more likely to experience this disease, which accounts for around 8.7% of global blindness. In 2020, around 196 million people will be impacted by AMD.44 Growing older, smoking, bad eating habits, hypertension, and physical inactivity are all risk factors. Although there are currently no therapies for AMD, appropriate care can slow its progression. Age-related macular degeneration is categorized as either dehydrated (atrophic or non-exudative) or wet (neovascular). The retinal epithelium shows unequal angiogenesis (the development of new blood vessels).45 Varshochian et al. produced albumin-PLGA NPs to contain bevacizumab. The resultant NPs produced a bevacizumab formulation that allowed for extended release, with a vitreous concentration more than 500 ng mL−1 in a rabbit model for about 8 weeks.46

Dry eyes

Dry keratoconjunctivitis, or dry eye disease (DED), is a multifactorial ocular surface disease. Tear film instability, hypertonicity and inflammation are its distinguishing features. Dry eye disease has a substantial impact on a patient’s quality of life, can cause mental health issues and imposes a significant financial cost on society. Dry eye disease is typically diagnosed and treated in 2 ways: aqueous tear-deficient dry eye and evaporative dry eye type. Artificial tears, local secretagogues, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants are common pharmacological therapies, although they can have negative side effects such as glaucoma, high IOP, poor patient adherence, and eye pain. Finding novel medication delivery strategies is critical for overcoming ocular obstacles and improving drug absorption.47 Dry eye disease complicates problems by increasing tear membrane osmolarity and causing ocular surface irritation. Traditional corticosteroids may increase IOP. Tet-ATS@PLGA is a novel nanomedicine with excellent biocompatibility, long-term release and anti-inflammatory effects. Following 2 weeks of treatment, the nanomedicine considerably lowers tear production and tear film breakdown times in a dry eye illness model. Li et al. demonstrated that apoptosis of inflammatory corneal epithelial cells inhibits the release of inflammatory mediators, thereby preventing DED formation and enhancing tear production.48 Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) NPs for ocular administration of cyclosporine A (CsA) to treat dry eye condition. The NPs were created using a solvent evaporation approach and their characteristics were evaluated using probe sonication. Wagh and Apar identified a 2-phase drug release mechanism, characterized by an initial rapid release followed by a sustained release. Enhancing the surface properties of NPs may improve drug absorption and retention in the eye, supporting the use of topical CsA as a safe and effective treatment for severe dry eye conditions.49

Retinoblastoma

The malignant tumor known as retinoblastoma usually affects youngsters under the age of 5. Untreated retinoblastoma leads to blindness and death (99%). It occurs in around one out of every 20,000 live births.50 It occurs at an equal rate in both genders. The cause is a mutation in the cancer suppressor gene RB1, which encodes the retinal tumor protein. Bilateral (40%) or unilateral (60%) retinal tumor protein might be used. Radiation, cryotherapy, systemic chemotherapy, and surgery are all options for treating retinoblastomas. Current research suggests the release of compensatory proangiogenic factors in response to anti-angiogenic therapies used for retinoblastoma treatment. A critical aspect in the treatment of retinoblastoma involves targeting the angiogenic phase, during which the tumor establishes new blood vessels essential for its growth and progression.51 Poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid NPs coated with curcumin or nutlin-3a are a unique approach to overcome the drug resistance of Y79 cells. Nutlin-3a is a potent medicine that acts as an antagonist of the murine double minute (MDM2), effectively inhibiting the interaction between p53 and MDM2. However, it acts as a substrate for Pgp and MRP-1, 2 multidrug-resistant proteins. It has relatively limited clinical use. Curcumin, a recognized regulator of multidrug resistance (MDR) proteins, may boost the anticancer activity of nutlin-3a in drug-resistant Y79 cells. The co-administration of folic acid functionalized targeted delivery system was discovered to improve its anticancer effects. The experiments on apoptosis, cell cycle analysis and in vitro cellular cytotoxicity confirmed the increased effectiveness of the folic acid functionalized NPs.52

The most popular and straightforward method of administering drugs to the eyes is the topical one (Table 153–58). It offers the advantages of 1) being comparatively noninvasive; 2) reducing the drug’s systemic adverse effects; and 3) being reasonably simple for patients to administer when compared to systemic administration. Ophthalmic solutions are therefore the first choice for treating a variety of eye conditions, including glaucoma, DED, infection, inflammation, and allergies. Roughly 95% of the currently available products in the global market for ocular medications are thought to be topical ophthalmic solutions.59 Subconjunctival administration is a minimally invasive and effective method for delivering drugs to the anterior eye chamber, avoiding corneal and BAB. However, it may result in drug loss due to drainage. Transscleral administration is simpler, less invasive and more suitable for patients, as it bypasses anterior obstacles and can deliver antioxidants, neuroprotective agents or anti-angiogenic agents to targeted retina sites.60 Intracameral administration injects drugs directly into the eye’s anterior chamber, avoiding adverse effects and first-pass metabolism. It is used for prophylactic antibiotics or anesthetics in eye surgeries. However, it requires reorganization, dilution of the injected drug solution, sterility, special preparations, and appropriate concentrations and doses, which can lead to corneal endothelial cell toxicity and toxic anterior segment syndrome.53 Intravitreal injections are a preferred method for treating eyeball diseases due to quick removal of free drugs. Frequent injections can cause side effects like retinal detachment and eyeball infection. The optimal protocol is a one-time injection without retracting the needle. Recent studies explore alternatives like NPs, implants, hydrogels, and minimally invasive techniques.54 Amphotericin B and chlorpromazine-loaded retrobulbar injections showed effective concentrations of both active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).55 Systemic administration is a drug delivery method for treating eye diseases like endophthalmitis, elevated IOP and uveitis, but frequent administration may cause side effects and poor patient compliance.56

Restrictions to use eye drops

Less than 5% of the amount of drugs applied topically penetrate the cornea and reach the ocular tissues, with a large percentage of the supplied dosage often being extensively absorbed by the nasal capillary channel and palpebral conjunctiva. Although many drugs have a short half-life and enter the systemic circulation quickly, ophthalmic solutions are extensively utilized because they are inexpensive, simple to create and manufacture, or have positive patient approval. Hypertension, bronchial asthma and tachycardia are examples of systemic adverse effects that could occur. Timolol eye drop has been shown to have such detrimental side effects.57

Colloidal system as a modified formulation for eye drops

The typical eye drops solution faces 3 major challenges: restricted bioavailability, non-targeted pharmacological effects and enzyme inactivation. Over the past 2 decades, substantial research has concentrated on colloidal carriers, including compact NPs, biodegradable polymeric NPs and liposomes, to overcome these limitations.58 While they provided some benefits for extended drug delivery, alternative ophthalmic distribution methods such as ophthalmic inserts and in situ gelling techniques failed to address the issues of blurred vision as well as the 4 main challenges previously identified: visual disturbances, eyelid adhesion, poor systemic absorption, and insufficient patient compliance. Liquid eye drops confront various obstacles including sediment formation, settling, lack of homogeneity, and resuspension difficulties. Particles larger than 1,000 nm can cluster and cause ocular irritation. Glaucoma, DR, macular degeneration, and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) all require continuous care.61 It is impossible to maintain therapeutic concentration with a single eye drop for a lengthy period of time. The conventional replacement ophthalmic implant provide regular drug delivery but have limitations: They are challenging to implement, particularly in the elderly and people who are visually impaired, and are often used incorrectly; moreover, they can be released from the eye and patient adherence is poor. The main challenges of ocular formulations are: pain and eyesight impairment, insertion difficulty, and potential elimination during the conclusion of their effective lives.62 The development of biodegradable and bio-erodible polymers, especially through aqueous-dependent colloidal nanotechniques, offers new potential for ocular medication delivery. Pharmaceutical scientists are increasingly interested in studying gene and protein alterations in eye drops, as well as medications containing NPs. These NPs may effectively target ocular tissues, are cost-effective and have great therapeutic efficiency.63

There are 2 ways to administer polymeric NPs: topically and intravenously. The injectable route is an invasive method for delivering therapeutic substances to ocular tissues since it contains colloidal drug-loaded NPs in a liquid medium with a viscosity similar to eye drop.64 Furthermore, it extends the residence period on the ocular surface and improves penetration, making medication administration via ocular barriers easier. Biodegradable polymers’ mucous adhesive characteristics lower the volume of fluid that drains from the outer layer of the eye by reacting with the existing mucus, therefore improving drug absorption and prolonging contact duration.65

Polymeric nanoparticles

Polymeric NPs are small, robust, colloidal molecules that range in size from 1 nm to 1,000 nm. Nanotechnologies create this innovative type of material to improve drug delivery and other therapeutic uses. Polymeric NPs could be modified for better selective distribution at the point of action or drugs bioavailability. They are widely used in drug delivery due to their high loading capacity, biodegradability and biocompatibility.66,67

Polymeric NPs are often used as drug delivery systems; they can transport both natural and synthetic molecules like as proteins, peptides, growth hormones, and pharmaceuticals. There are 2 types of NPs that have distinct structures: nanospheres and nanocapsules. Medications can be absorbed onto the surface of nanospheres or kept inside their dense polymeric matrix. The drug, genetic material and other components are integrated into the nanocapsules’ liquid/solid core, which is protected by a unique polymeric membrane.68

Types of polymeric nanoparticles

There are 2 types of polymeric NPs usually employed to create NPs: synthetic and natural. Polymeric NPs in ocular drug delivery systems are made from a variety of polymers (Table 2 69–73).

According to Kalam et al., tedizolid phosphate (TZP) can be administered ocularly using noninvasive chitosan NPs (CSNPs) to treat Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. The CSNPs demonstrated better drug loading and encapsulation and in rabbits, they caused no eye irritation indicating their potential for top-up application.74 Polymeric NPs loaded with lutein have demonstrated long-term stability and sustained distribution within the ocular tissues. Swetledge et al. found that NPs were significantly absorbed, particularly in the choroid, and then rapidly eliminated.75 Fenofibrate improves retinal degeneration and DR, although its solubility may limit therapy efficacy, as demonstrated by Khin et al. A water-soluble fenofibrate (FE)/cyclodextrin complex with increased solubility was developed employing polymers such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose.76 Naproxen-Eudragit RS100 NPs prepared using single emulsion technique showed lower crystallinity and slow drug release.77

Natural polymers

There are numerous plant and animal sources of natural polymers. In addition, the cost is reasonable. Natural polymers are frequently biocompatible and nontoxic at a wide range of dosages. These can be synthesized using complex multi-step procedures or extracted from raw materials via laborious separation methods. Examples are albumin and chitosan.78,79

Synthetic polymers

Synthetic polymers are produced by polymerization procedures involving numerous monomer units and are rare in nature. They are often created utilizing modern growth technologies using petroleum-based raw materials. Due to their perfectly defined chemical structures, synthetic polymers allow for easier adjustment of their chemical and physical properties than natural polymers. Compared to organic materials, these artificial polymers offer greater control and versatility. Their tunability enables precise management of API release and they can be made to have mechanical properties comparable to those of biological tissues. Examples are PLA, poly(caprolactone), poly(acrylic acid), poly(vinyl alcohol), poly(cyanoacrylates),

and PLGA NPs.80,81

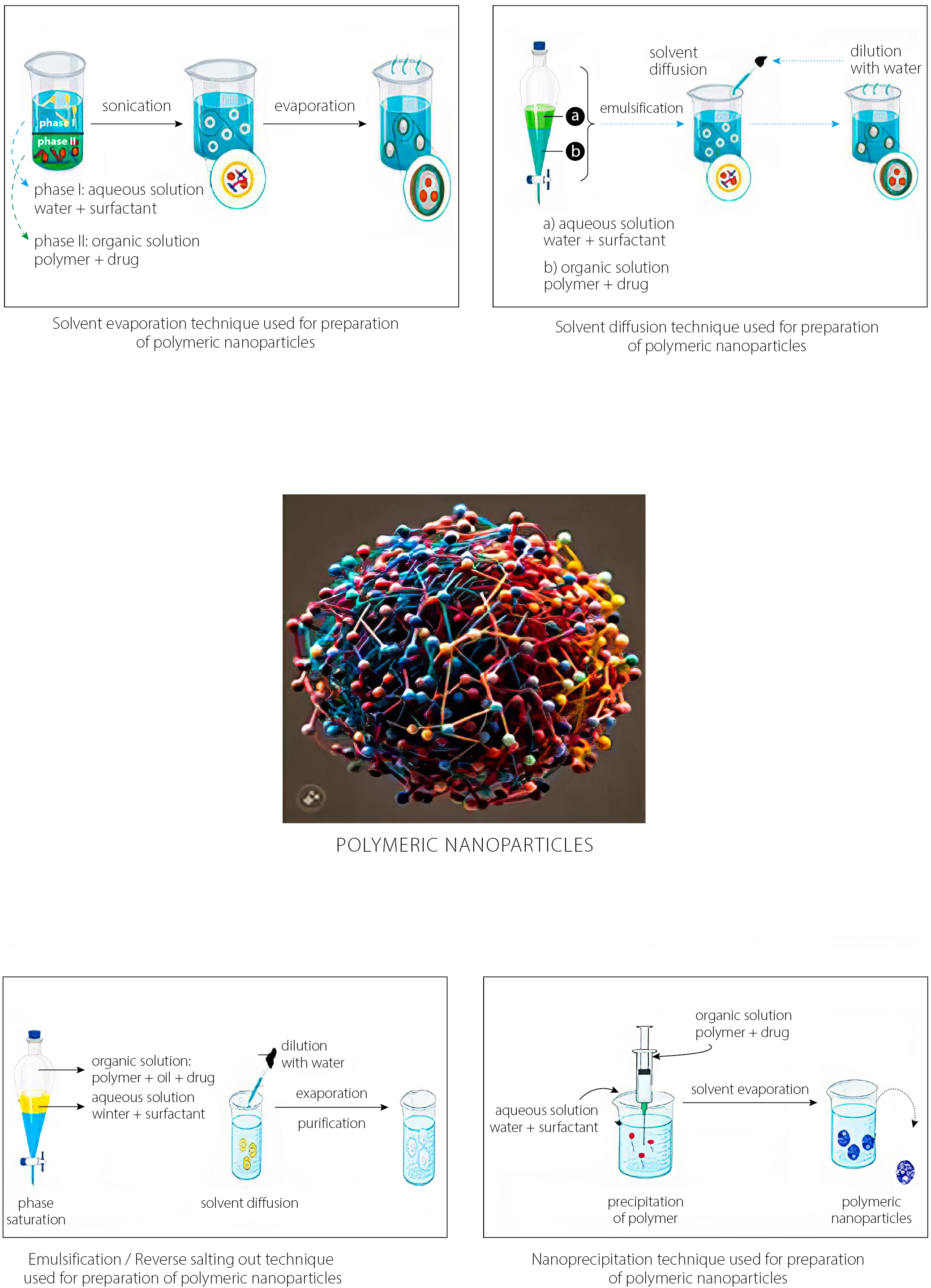

Methods of preparation to develop polymeric nanoparticles

The various methods used to prepare the polymeric NPs are presented in Figure 2. The type of medication contained within the polymeric NPs influences the specific delivery technique.82 Typically, the 2 main strategies used involve the dispersion of existing polymers and the polymerization of monomers, which are both dual in nature.83 Biological diluents are often used during the 1ststage of several polymer preparation techniques to aid the solubilization of the polymer.84 The usage of these diluents can raise concerns about toxicity and risks to the environment. Furthermore, the final product must accommodate solvent residues. Monomer polymerization techniques make it possible to efficiently coat substances with polymeric NPs in a single reaction step. Regardless of the preparation process utilized, the end result is usually aqueous colloidal suspensions.85

Solvent evaporation

The primary method for producing polymeric NPs is solvent evaporation from a pre-formed polymer. This process generates nanospheres through an oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion. The organic phase is prepared by vigorously mixing or dissolving an active compound in an organic solvent. However, this can cause polymer degradation. Dichloromethane and chloroform were commonly used solvents in the past. Due to their toxicity, ethyl acetate has now become the preferred alternative.86 In the initial stage, biological diluents are often used to solubilize the prepared polymers.87 During the aqueous phase, the organic solution is mixed with a surfactant. This mixture is homogenized and ultrasonicated at high speeds to create suspended nanodroplets. As the polymer solution evaporates, NPs remain suspended in a stable emulsion. If the solvent is polar, evaporation occurs gradually under low pressure or with continuous magnetic stirring at room temperature. Once the solvent completely evaporates, NPs can be collected and purified by centrifugation. Freeze-drying is then used for long-term storage. This approach is effective and widely used for producing uniform polymeric nanospheres.88

Solvent diffusion

This approach combines an aqueous solution with a surfactant and a relatively water-miscible polymer solution containing a drug to form an oil-in-water (o/w) dispersion. To achieve kinetic equilibrium in a 2-stage process at room temperature, an organic solution – such as benzyl alcohol mixed with ethyl acetate – is used as the internal phase of a water-saturated colloid.89 Significant dilution enhances solvent diffusion from the dispersed droplets into the external aqueous phase, promoting the formation of suspended particles. This method is widely employed to produce nanospheres or nanocapsules. In some cases, the final step can be eliminated through simple filtration or evaporation. The resulting NPs typically range in size from 80 nm to 900 nm. Adjustments to process parameters allow for control over particle size within this range. Although effective, this method may lead to partial diffusion of water-soluble drugs into the aqueous phase, potentially reducing drug encapsulation efficiency.69

Emulsification/reverse salting-out

Solvent diffusion techniques such as emulsification or reverse salting-out are commonly used to produce polymeric nanospheres. The salting-out method facilitates NP formation by removing hydrophilic solvents from the aqueous phase. The key difference lies in how an oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion is created. A water-miscible polymer solvent – such as ethanol or acetone – is combined with a salting-out agent and a colloidal stabilizer in the aqueous phase. Salting-out agents include electrolytes like magnesium chloride, calcium chloride and magnesium acetate (Mg (CH₃COO)₂), as well as non-electrolytes such as sucrose. Saturation of the aqueous medium reduces the miscibility between acetone and water. This enables the formation of 2 distinct solubility phases and supports o/w emulsion formation.70 At room temperature, continuous stirring promotes stable emulsion development. Polymer precipitation occurs as the polymer diffuses from the organic solvent into the outer aqueous phase. This leads to nanosphere formation.71 The resulting emulsion is then diluted with a defined amount of aqueous solution and deionized water. Filtration removes residual solvent and salting-out agents through cross-flow separation. Although this method simplifies processing, complete water solubility of the organic solvent is not required. The technique yields nanospheres ranging from 170 nm to 900 nm. By adjusting polymer concentration, average particle size can be fine-tuned between 200 nm and 500 nm.72

Nanoprecipitation

This approach, also known as the solvent displacement technique, involves 2 miscible solvents. A soluble organic solvent – such as acetone or acetonitrile – is used to dissolve the polymer and form the organic phase. Evaporation effectively removes the solvent, as it does not mix with water.73,90–92 After solvent elimination, the polymer forms an interface in a lipophilic solution before being injected into the aqueous phase. This step is essential for NP formation. The polymer, dissolved in a moderately polar, water-soluble solvent, is slowly added to an aqueous medium under agitation, typically dropwise.93

As the polymer solution enters water, it rapidly diffuses and separates from water molecules. This promotes the immediate formation of NPs. Although the aqueous and organic phases typically interact simultaneously, procedural variations can still yield NPs.94

Surfactants play a crucial role in stabilizing the colloidal suspension during the process. Nanoparticles produced by the emulsification-solvent evaporation method often display uniform size and narrow size distribution compared to other methods.95 Nanoprecipitation is a widely used method for producing nanospheres or nanocapsules, typically yielding polymeric NPs around 170 nm in diameter. This method involves dissolving or dispersing the active compound within the polymeric solution to form nanospheres. To form nanocapsules, the drug is first dissolved in oil and then emulsified into the organic polymeric phase before the internal stage begins.96

Characterization of polymeric nanoparticles

The physical properties of polymeric NPs vary depending on their composition, concentration, size, shape, surface qualities, crystallinity, and dispersion stage. The physical properties of polymeric NPs vary with their composition, concentration, size, shape, surface characteristics, crystallinity, and dispersion state; therefore, their comprehensive characterization is essential. Typically, a variety of techniques are employed to analyze these properties. One of the most frequently used by electron microscopy, electrophoresis, chromatography, near-infrared spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering (DLS), or photon correlation spectroscopy (PCS) and electrophoresis.97,98 The examination of polymeric NPs is critical for finding difficulties with nanotoxicology and occupational exposure evaluation, both of which are required for regulating industrial processes and identifying health and safety risks.99

Morphology

Scanning and transmission electron microscopy (SEM and TEM) are commonly used to analyze the form or size of polymeric NPs, frequently in conjunction with cryofracture procedures. Transmission electron microscopy can distinguish between nanocapsules and nanospheres, as well as determine the thickness of the nanocapsules wall. Atomic force microscopy provides significant information on the surface morphology of NPs, revealing intricate topography, tiny cavities and pores.100,101

Particle size distribution

Polymeric NPs have an average size of 100–300 nm and a polydispersity of near 0. They can also be smaller than 50 nm or between 60 nm and 70 nm.102 Size measurements are performed utilizing techniques such as dynamic or static light scattering. Quantitative composition, oil type and medicine dosage all have an effect on NP size. The DLS and SLS measurements can yield information on particle size distribution and aggregation state.103

Chemical composition and crystal structure

Chemical composition refers to the atomic elements and compounds found in NPs, which can be determined using single-particle elemental analysis methods.104 Atomic absorption spectroscopy is a typical technique for measuring sample mass concentration by comparing the signal with calibration standards. Time-of-flight mass spectrometry is another method for determining the chemical composition of a single particle.105 Crystal structure can be elucidated using powder XRD.106

Molar mass distribution of polymer

Drug-polymer interactions and polymer degradation have an impact on ingredient formulation due to their polymeric molecular dispersion. Size-exclusion chromatography and static light scattering are 2 regularly used techniques for this purpose.107

Surface area and chemistry

The surface area of NPs is critical for reactivity and ligand binding. Adsorption of inert gas is measured under various pressure settings to form one layer.108 Nanoparticles significantly affect solvent interactions due to the large number of atoms present on their surfaces. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and secondary ion mass spectroscopy are used to study the surface chemistry of these NPs.109

Zeta potential

The zeta potential is a critical characteristic that affects the surface charge of NPs. It is determined using Doppler techniques and influenced by factors such as functional group dissociation, ionic species adsorption and solvation effects. Polymeric NPs, such as those derived from poloxamers and other polymers, might influence zeta potential. A strong zeta potential is required to maintain the stability of colloidal suspensions.110

pH of suspensions

The stability of NP solutions can be better assessed through regular pH monitoring. Variations in pH may indicate the degradation of polymers, as evidenced by the condition of nanocapsules and nanospheres after 6 months of preservation.111 This decrease in stability is related to carboxylic group ionization, hydrophobicity alterations and zeta potential changes, emphasizing the importance of pH monitoring in maintaining formulation integrity.112

Stability of polymeric NPs suspensions

During long-term storage, polymeric nanosuspensions are converted into colloidal suspensions due to slow deposition and Brownian motion.113 Adsorption of active compounds and surfactants is one of the factors that influences their stability. Physicochemical factors such as particle size, zeta potential, polymer mass distribution, drug content, and pH can be used to assess their stability. However, industrial applications of polymeric NPs may be limited due to extended storage durations and low physicochemical stability.114 To delay these concerns, drying methods like lyophilization or spray drying are recommended. Lyophilization removes water through sublimation, and spray drying facilitates the quick drying of droplets.115

Determination of the drug association

Nanoparticles’ small size makes it difficult to distinguish between free and bound drug fractions, complicating the measurement of drug association with them. Drug concentration is measured using ultracentrifugation and ultrafiltration-centrifugation techniques.116 Several factors influence the dose of pharmaceuticals in nanostructured systems, including the drug’s physicochemical qualities, pH levels, polymer surface features, formulation order, oil type, and surfactants adsorbed onto the polymeric surface. Improving the surface characteristics of particles can result in various levels of drug association, which is critical for extending the drug’s effects.117 Drug adsorption isotherms on NP surfaces give information about drug distribution and association capacity. Detecting drug association mode is difficult since current techniques only evaluate the concentration of medicine coupled with NPs. Additional approaches include XRD or infrared spectroscopy.118

Pharmaceutical in vitro release kinetics

Drug release from polymeric NPs is determined by factors like desorption, matrix erosion, diffusion, or a combination of these mechanisms. Low-pressure filtration and ultrafiltration-centrifugation are 2 methods used to explain drug release from NPs. Drug release kinetics in nanospheres are typically exponential, whereas medication in nanocapsules has zero order kinetics when released via the polymeric membrane.119

In vitro and vivo toxicological studies

The use of NPs for drug delivery has several advantages, including increased stability and the capacity to encase active molecules. Nonetheless, the potential for nanotoxicity remains a major concern to be addressed.120 Studies have shown that non-biodegradable and reversible polymer nanocarriers can be employed efficiently for ocular medication delivery. Biomimetic technology is used to develop more effective nanocarriers. Biodegradable synthetic polymers are widely used in medical applications. Examples include PLA and PLGA. These polymers are safe, biocompatible and show low immunogenicity and toxicity. Polymeric NPs, which are known for their high drug encapsulation efficiency and ease of manufacture, are widely employed in tissue engineering, drug delivery, biological sensors, and the development of biomimetic materials. Their possible applications are influenced by size, surface charge, hydrophilicity, hydrophobicity, and polymer type.121

The cytotoxicity of NPs is tested in vitro using colorimetric analysis. Jain and Thareja focused on PLGA NPs containing triterpenoids with possible anticancer capabilities and compares their effects on HepG2, Caco-2 and Y-79 cells. When the NPs were loaded with both natural and synthesized mixtures of oleanolic and ursolic acids, cell viability increased considerably.122 Polyethylene glycol was added to the surface of dexibuprofen-loaded PLGA NPs to help them stay in the ocular mucosa longer. These nanospheres are less toxic to cells than free dexibuprofen and have been shown to be non-irritating in both in vitro and in vivo studies. Pranoprofen, another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), has been improved by coating with PLGA nanospheres, which are non-cytotoxic to Y-79 cell lines. The use of polystyrene NPs in topical applications has shown that they accumulate at follicular apertures, resulting in excellent drug delivery with minimal toxicity. The discussion also covers biomimetic tactics like cell membrane camouflage and functionalization. A new pH-responsive copolymer has been designed to produce biocompatible and biodegradable NPs for chemotherapeutic drug delivery. These nanosystems, known for their powerful anticancer properties, have been examined both in vitro and in vivo. They have a crosslinked bovine serum albumin shell that does not harm normal tissues.123

Applications of polymeric nanoparticles in ocular delivery

Polymeric NPs have gained significant interest in ocular medicine for their ability to provide regulated drug release, improved biodegradability and drug bioavailability. The use of these NPs in ocular therapeutics efficiently resolves difficulties such as quick drug clearance through tears and restricted drug absorption in ocular tissues. The following are some notable applications of polymeric NPs in eye therapy (Figure 3, Table 3124–168).169,170

Antibacterial

A new treatment for bacterial keratitis, a condition that can cause to blindness and vision loss, has been developed using ciprofloxacin in conjunction with a mixture of glycol chitosan and PLA. The NPs obtained by Padaga et al. showed a significant antibacterial response against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and were effective in inhibiting bacterial quorum sensing. In vivo research demonstrated good ocular retention and a reduction in bacterial loads.171

Gemifloxacin (GM) has a longer residence time than the free drug in deep tissues and on the ocular surface. Eight types of GM NPs were created using the precipitation method triggered by sodium tripolyphosphate to produce chitosan polymer. The formulated NPs had an average entrapment efficiency of 46.6% and a cumulative release of 74.9%. Studies in rabbits showed a significant increase in GM concentration, improved trans corneal penetration and increased antibacterial effectiveness.172 Moxifloxacin (MOX) hydrochloride is used to treat ocular infections, such as bacterial conjunctivitis. This drug is a fluoroquinolone antibiotic. It works by eliminating the microorganisms that cause conjunctivitis. Kırımlıoğlu et al. aimed to improve ocular absorption by increasing the carrier’s interaction time with the ophthalmic membrane. Moxifloxacin hydrochloride was integrated into cationic Eudragit® RS 100 NPs via spray-drying technique. The formulations were characterized, and MOX was quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. The cytotoxicity tests found no negative effects after 24 h.173

Khan et al. investigated a NP-based approach to enhance ocular retention and drug bioavailability for the prolonged delivery of moxifloxacin (MOX). By utilizing PLGA matrix-forming polymers, the NPs were optimized for size, stability and polydispersity index. They found that the NPs exhibited high initial release rate and a prolonged drug release through diffusion, with a low clearance rate and elevated maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), area under the curve (AUC) and mean residence time (MRT) in comparison to commercial eye drops. These results suggest that PLGA NPs significantly improve the bioavailability of MOX hydrochloride.174

Conjunctivitis is a common infection of the ocular surface that is normally treated with eye drops. Unfortunately, these drops may lose up to 95% of their medicament. A promising novel treatment uses PLGA NPs coated with chitosan and containing levofloxacin efficiently treat bacterial conjunctivitis. These NPs were evaluated concerning their size, drug absorption rates, entrapment efficiency, drug release profiles, ex vivo permeation, ophthalmic compatibility, antibacterial capabilities, and assessments utilizing binocular laser microscopy and gamma scintillation. The adjusted formulation demonstrated increased penetration, considerable antibacterial activity and an extended corneal residence duration.175

Gatifloxacin’s ocular bioavailability was improved by embedding it in cationic polymeric NPs. The optimized formulation had a drug loading of 46%, acceptable levels of cytotoxicity and a sustained release rate. The underlying hypothesis is that these NPs increase GM’s residence time.176

To overcome the challenges associated with drug delivery to the ocular region, the team developed and evaluated levofloxacin-encapsulated PLGA NPs, focusing on various characteristics such as ex vivo trans corneal permeability, zeta potential, in vitro drug release, and particle size. The NPs achieved a drug entrapment efficiency of nearly 85%, with an average particle size ranging from 190 nm to 195 nm. Furthermore, they demonstrated non-irritating characteristics, achieving an average score of 0.33 over a 24-h period in the hen's egg test-chorioallantoic membrane (HET-CAM).177 Drugs with low ocular bioavailability, in contrast to conventional eye drops, face physiological barriers within the eye. To enhance ocular effectiveness, researchers are creating PLGA NPs to improve the distribution of sparfloxacin in the eye. These NPs exhibit a zeta potential of −22 mV and an average particle size ranging from 180 nm to 190 nm, making them suitable for ocular applications. Gupta et al. demonstrated significant retention in the precorneal area, remaining in the eye for a longer duration compared to standard commercial formulations.178

Moxifloxacin, a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone antibiotic, is commonly employed in the treatment of ocular infections such as keratitis and conjunctivitis. Its efficacy against Gram-negative bacteria is similar to that of ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin, while also demonstrating superior penetration into inflamed ocular tissues. Researchers have created nanoformulations encapsulating MOX to enhance ocular absorption, minimize side effects and improve patient adherence.179

Antifungal

Polymeric NPs are a viable approach for improving antifungal drug delivery in ocular applications, overcoming problems in getting antifungal medicines to the eye.

Cyclosporine A is used as an immunosuppressive, antiviral and anti-inflammatory medication to treat dry eye. Experimental results show that CsA can increase the antifungal activities of azoles, including voriconazole, by killing both planktonic cells and biofilms. Research of PLGA NPs discovered that voriconazole-loaded PLGA NPs did not significantly improve antifungal efficacy. However, PLGA NPs loaded with voriconazole and CsA displayed higher antifungal activity.180

Voriconazole, a triazole antifungal, is used to treat particular fungal infections and severe fungal illnesses. Mohammadzadeh et al. produced voriconazole-loaded chitosan NPs utilizing ionic gelation and sodium tripolyphosphate to create a topical ocular delivery system. The NPs were investigated using XRD, DSC, SEM, and FTIR. A Box–Behnken design was devised, and the formulation showed substantial drug loading, no burst effect and a 48-h sustained drug release time, making it useful for eye delivery.181

Fluconazole’s efficiency in treating infections can be enhanced by generating fluconazole-loaded polymeric NPs using a variety of polymers and processes. The NPs were created utilizing a twofold emulsion/solvent evaporation technique and ionotropic pre-gelation procedures. NP4 was chosen for in vitro release testing against a C. albicans resistant strain. This formulation displayed an initial fast release followed by a sustained release profile over a full day, resulting in a 20-fold reduction in fluconazole’s minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). As a result, fluconazole’s antifungal potency against C. albicans increased significantly.182

To improve the antifungal properties of chitosan, emphasizing its potential for treating eye illnesses, these NPs were combined with sodium tripolyphosphate (CTS) and natamycin (NAT) to increase their inhibitory effects on C. albicans. The results suggested that NAT-NPs had a higher inhibitory concentration (IC50) and a wider area of inhibition against C. albicans than natamycin.183 To improve the ocular distribution and antifungal activity of terconazole (TCZ) by creating cationic polymeric NPs containing TCZ. The NPs were evaluated using a variety of methodologies, including FTIR, entrapment efficiency testing and X-ray powder diffraction. They demonstrated prolonged antifungal activity for up to 24 h and were more effective against C. albicans than regular TCZ. Mohsen proposed that cationic polymeric NPs may be an efficient drug delivery strategy to increase the ocular antifungal effects of TCZ.184

Keratitis caused by fungi is the leading cause of blindness worldwide. Amphotericin-B is the primary treatment for fungal infections, although its low precorneal retention reduces its efficacy. To overcome this issue, Chhonker et al. developed lecithin/chitosan NPs that encapsulate amphotericin-B for long-term ocular administration. These NPs have enhanced antifungal activity against Aspergillus fumigatus and C. albicans, as well as higher bioavailability and precorneal residence duration.185

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatorys

Ocular inflammation is a common problem in ophthalmology and it is frequently treated with NSAIDS such as ibuprofen. However, these medicines have very low absorption in ocular tissues, with fewer than 5% being efficacious. Biodegradable polymeric PLGA NPs offer a viable alternative to traditional eye drops, with the goal of reducing side effects and increasing bioavailability. Solvent displacement procedures were used in conjunction with surfactants to create dexibuprofen-encapsulated formulations.186

Aceclofenac is a NSAID that can be used to treat ocular inflammation. It acts by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are involved in the formation of prostaglandins, a chemical messenger that contributes to inflammation and pain. The purpose of the study by Katara and Majumdar was to develop aceclofenac NPs using the direct precipitation method. These spherical NPs were shown to be suitable for intraocular delivery. They showed Higuchi square root release kinetics and a prolonged in vitro drug release profile, achieving a twofold increase in penetration compared to an aceclofenac water-based solution.187

Pranoprofen is an anti-inflammatory drug made of PLGA NPs that protects against strabismus and cataract surgery. It has been evaluated for cytotoxicity, corneal absorption, ocular compatibility and therapeutic efficacy, with no symptoms of toxicity.188 Diclofenac sodium is a NSAID that is used topically to the eye to relieve inflammation, irritation and light sensitivity, especially following cataract extraction or refractive surgery. It works by inhibiting the production of specific chemicals that cause inflammation and pain. The goal of the study by Asasutjarit et al. was to improve the ocular bioavailability of diclofenac sodium (DC) by developing diclofenac sodium-trimethyl chitosan NPs (TMCNs) for use in ophthalmology. The ionic gelation process was used to generate DC-TMCNs with various compositions, enabling for evaluation of their physicochemical properties, drug release potential, risk of ocular irritation, and absorption in the eye. DC-TMCNs reached a zeta potential of +4 mV.124

Aceclofenac is a NSAID that can be used to treat ocular inflammation. Katara et al. developed formulation of aceclofenac NPs using Eudragit RL 100 resulted in a sustained in vitro release pattern consistent with Higuchi square root kinetics. This NP formulation increased drug penetration in excised corneas. It decreased lid closure scores in rabbits with arachidonic acid-induced ocular inflammation. It also reduced polymorphonuclear leukocyte migration in these rabbits. The formulation remained stable for over 2 years.125

Using a goat cornea-based experimental model, Ahuja et al. investigated how medicinal components alter diclofenac absorption. The oil-in-water emulsion solvent evaporation method was used to combine diclofenac sodium and Eudragit RS 100. These formulations exhibited a high zeta potential. They had an optimum particle size and efficient drug entrapment, and demonstrated a prolonged release of the medication in vitro without generating any discomfort in ocular tissues. The drug release mechanism was discovered as non-Fickian, with matrix diffusion control playing the key role.126

Steroids anti-inflammatory drugs

Steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines, often known as corticosteroids, are used in ophthalmology to treat eye irritation. They function by lowering the immune response and inflammation, which can be helpful in situations like uveitis and following surgeries like cataract extraction. Xing et al. aimed to improve the design of chitosan (CHT)-coated PLGA NPs containing triamcinolone acetonide (TA). The PLGA NPs infused with TA revealed potent anti-inflammatory activities, reduced levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6), alleviated inflammatory symptoms in rabbits, and demonstrated better transparency in aqueous humor compared to normal levels.127 The ocular anti-inflammatory drug atorvastatin calcium was integrated into a polymeric NP to improve surface properties and allow for longer release. Four formulations were examined to assess their ocular irritation and efficacy in resolving inflammation caused by prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).128 Nanoparticles made of PEG and PLGA, functionalized with cell-penetrating peptides and loaded with fluorometholone, have been developed for the treatment of eye irritation. These NPs revealed acceptable qualities for ocular administration and had anti-inflammatory effects in human corneal epithelial cells and mouse eyes, potentially providing a unique technique for managing ocular inflammatory disorders.129

Fluorometholone is an anti-inflammatory corticosteroid that is applied topically to the eyes to treat a variety of problems such as inflammation, allergies and postoperative recovery. It helps to minimize edema and redness in the eyes. Compared to some other corticosteroids, it is usually thought to have a lesser risk of elevating IOP. Gonzalez-Pizarro et al. aimed to produce and improve PLA NPs containing fluorometholone for the treatment of ocular inflammation. The resultant NPs, with an average particle size of less than 200 nm and a negative surface charge of −30 mV, were found to be acceptable for ocular applications. They showed greater corneal penetration and higher anti-inflammatory effects than current commercial medications, implying that they could be used as an effective alternative to traditional topical therapy.130 To increase the efficacy of TA in the treatment of endotoxin-induced uveitis by using a modified emulsification/solvent diffusion approach, in vivo tests were conducted using PLGA NPs with a drug loading of 3.16%, and inflammatory parameters were measured in rabbit eyes. Furthermore, inflammatory mediators were assessed 3 h after injection.131 Gelatin NPs containing hydrocortisone or pilocarpine HCl were created using the desolvation method. The pH affects particle size but does not modify their properties. Furthermore, a high level of pilocarpine HCl was successfully encapsulated within both types A and B gelatin particles, resulting in the formation of a compound.132

Antibiotics

A new formulation of vancomycin (VCM)-loaded N, N-dodecyl, methyl-polyethylenimine NPs integrated with HA, has been created to improve the treatment of bacterial endophthalmitis. The NPs showed high bactericidal activity and ocular compatibility, with a zeta potential of +26.4 ±3.3 mV and a 93% encapsulation rate for VCM. They were discovered to be non-irritating and non-toxic to emerging retinal pigment epithelia-19 (ARPE-19) cells, indicating that their use coupled with HA may provide further therapeutic benefits.133 The use of mucous adhesive chitosan-loaded alginate (CS-ALG) NPs is a promising technique for providing daptomycin to the eye epithelium, potentially enhancing the treatment of bacterial Endophthalmitis by boosting drug permeability and retention in the eye.134 In some studies on development of amikacin-loaded polymeric NPs, effective distribution of amikacin was observed. Sharma et al. examined characteristics such particle size, zeta potential and antibacterial effectiveness against S. aureus. These NPs were used to create tear films and showed compatibility with the Korsmeyer–Peppas model.135

Doxycycline is a tetracycline antibiotic. It treats illnesses through preventing the growth and spread of bacteria. Polymer-surfactant NPs containing doxycycline hydrochloride (DXY) were created to improve to improve the drug’s penetration and retention time in the eye. These NPs were analyzed for their antibacterial characteristics and potential to induce eye irritation, demonstrating their safety and effectiveness for sustained delivery of ocular medicine.136 Biodegradable NPs containing clarithromycin shown antibacterial activity against S. aureus. The NPs exhibited a constant size distribution and a spherical shape, indicating decreased drug crystallinity and the existence of noncovalent interactions.137

Antioxidants

Rosmarinic acid, a natural antioxidant found in plants such as rosemary, may provide significant benefits for eye health due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Chitosan NPs were used as natural carriers for rosmarinic acid, encapsulating extracts from Satureja montana and Salvia officinalis. Chitosan and sodium tripolyphosphate were combined in a 7:1 weight ratio at pH 5.8, resulting in NPs ranging in size from 200 nm to 300 nm. When delivered to human corneal cell lines and the retina pigment epithelium, the NPs showed no obvious cytotoxicity.138 Lutein is a potent antioxidant and carotenoid that is essential for ocular health, notably in protecting the macula. It can help reduce inflammation, combat oxidative stress and possibly prevent or slow AMD. Carter et al. examined the use of lutein-loaded polymeric NPs as therapeutic delivery vehicles for ocular illnesses, including their stability and distribution. Their findings suggest that there is significant absorption in ocular tissues, with the choroid having the highest uptake.139

Antiviral drugs

Acyclovir-containing nanosphere colloidal solutions were investigated as possible ocular medication delivery vehicles. Pegylated 1,2-distearoyl-3-phosphatidylethanolamine was added to PLA nanospheres. The ocular pharmacokinetics of acyclovir-loaded NPs were observed in vivo and compared to an aqueous suspension of the free medication. Giannavola et al. found that when the surfactant concentration grew, the average size and relative zeta potential of PLA nanospheres dropped. The PEG-coated nanospheres performed better than standard PLA nanospheres.140

Immunosuppressant

The current options of extraocular disease treatment is limited because of the difficulties in providing medications without harming intraocular structures or resulting in systemic drug exposure. De Campos et al. investigated the potential of chitosan NPs in new drug delivery methods for the ophthalmic mucus. Cyclosporin A was chosen for the model chemical. The NPs demonstrated high loading and CsA interaction efficiency, resulting in fast release in vitro and steady release in vivo.141

Dual dosage form

Polymeric NPs (PLGA NPs) of sertaconazole (STZ) has been used as delivery vehicles to increase ocular availability for the treatment of fungal keratitis. The nanoprecipitation process was employed to generate STZ-loaded PLGA NPs, which were then optimized using a 24-full factorial. The hydrodynamic size of PLGA NPs was increased by incorporating PEG 2000 in a solid dispersion containing sertaconazole. STZ-PEG2000-loaded PLGA NPs demonstrated a 2.5 increase in permeability through rabbit cornea and a fourfold decrease in MIC value against C. albicans.142

Developed and analyzed an improved formulation of fluconazole polymeric NPs, with a focus on its efficacy against a well-known C. albicans variety. These enhanced NPs were mixed into 2 different ophthalmic formulations. To assess the efficacy and safety of the produced product, Almehmady et al. looked into the ophthalmic formulations’ rheological features, in vitro drug release, stability, and ocular delivery.143 To improve norfloxacin (NFX) ocular absorption by creating hydrogels containing NFX-loaded NPs, they were created utilizing a double-emulsion/solvent evaporation technique with PLGA polymer. The selected NPs were spherical, had acceptable properties and showed promising antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa. The hydrogels were thixotropic, pseudoplastic, spreadable, transparent, and produced better drug penetration and long-term release. The G3 and G4 systems showed encouraging antibacterial activity.144

Salama et al. focused on how nanotechnology and bio-adhesive gel can potentially be used to create an ocular drug delivery system that reduces eye irritation. They highlighted the impact of formulation factors on drug entrapment efficiency, particle size, and polydispersity index. The optimized formulation LPCL-NP2 encapsulates ofloxacin in a spherical shape and the drug’s amorphous form was confirmed with DSC analysis. The NP formulation was tested on rabbits with Escherichia coli infection and showed remarkable antibacterial effectiveness and low bacterial growth.145 To increase fluconazole ocular penetration by creating and characterizing NPs by antisolvent precipitation nanonization, various surfactant concentrations were investigated and the ocular pharmacokinetics of a gel with a suitable drug NP composition was studied in rabbits. El Sayeh et al. found that NP formulations improved ocular diffusion findings. Formula F3 had the highest ex vivo release rate (100% after 6 h) and a narrower particle range (352 ±6.1 nm), with a zeta potential charge of −18.3 mV. The ocular gel containing fluconazole NPs improved ocular pharmacokinetic properties and increased medication corneal penetration.146

Thermosensitive gels have been developed to enhance ophthalmic anti-inflammatory efficacy by transforming into gels at corneal temperature and allowing appropriate release of PLGA NPs encapsulated with fluorometholone. These gels prevent initial drug release bursts and increase precorneal residence time, allowing for increased eye drop dosing. Gonzalez-Pizarro et al. showed that no formulation causes eye discomfort, indicating that they are effective for the acute and preventive control of ocular inflammatory disease.147

For improvement of ocular bioavailability, VCM-loaded polymeric nanoparticles were prepared and incorporated into chitosan-based gel by using double emulsion solvent evaporation technique. The Draize test confirmed that these formulations are non-irritating and suitable for ocular use. Microbiological susceptibility tests showed longer retention timeas and increased Cmax levels and AUC. Consequently, VCM-loaded polymeric NPs are viable carriers for improving the distribution of VCM in ophthalmic applications.148

Levofloxacin, an antibacterial drug, was successfully encapsulated in chitosan NPs. Ameeduzzafar et al. used chitosan NPs to encapsulate levofloxacin, which proved to be an efficient treatment for eye infections. The NPs were created utilizing an ionic gelation process, which resulted in a high drug loading capacity and nanoscale particle size. The formulation was shown to be safe and non-irritating, with increased antibacterial activity against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. The in situ gel approach for levofloxacin-coated chitosan NPs demonstrated beneficial outcomes.149

Expert opinion

In recent years, ophthalmology has made significant progress in resolving critical issues related to drug delivery to ocular tissues. Traditional ophthalmic dosage forms such as eye drops, ointments and gels frequently have low bioavailability and short drug retention time on the ocular surface, necessitating repeated administration and decreasing patient compliance. In response to these limitations, there has been a gradual shift to more modern drug delivery technologies, particularly colloidal formulations such as polymeric NPs. These nano-sized carriers have various advantages, including the capacity to encapsulate a wide range of medications, increased drug solubility and sustained and targeted delivery to ocular tissues. Despite these promising developments, employing polymeric NPs still faces a number of challenges, as evidenced by in vitro and in vivo studies, such as reproducibility, scalability and regulatory approval, which impede the seamless transition from laboratory research to clinical use.

Nonetheless, polymeric NPs continue to pique interest due to their distinct and advantageous features. These systems are built from a variety of natural and synthetic polymers, each with a particular viscosity grade and molecular weight that can be tuned to accomplish unique drug release profiles and therapeutic goals. By addressing these features, we can design dosage forms that are safe, biocompatible and exceptionally effective at delivering drug over long periods. Polymeric NPs, which are specifically designed for regulated and prolonged drug release, have the potential to reduce dose frequency while improving treatment outcomes for a variety of ocular diseases such as glaucoma, conjunctivitis, uveitis, and retinal disorders. Extensive preclinical research has focused on refining formulation properties such as particle size, surface charge and hydrophilicity in order to improve tissue penetration, reduce ocular irritation and extend medication retention time in the eye. Polymeric NPs have strong potential for ocular drug delivery. Their small particle size facilitates penetration through ocular barriers, while their inherent biocompatibility minimizes toxicity and patient discomfort.

Conclusions

This review emphasizes the considerable and growing promise of polymeric NPs in both the diagnosis and treatment of a wide range of ocular diseases. Over the years, polymeric NPs have emerged as innovative and highly versatile drug delivery systems that overcome many limitations associated with conventional ocular formulations. Their ability to offer previously unrecognized capabilities such as precise targeting, sustained drug release and improved therapeutic efficacy has created new opportunity for the management of challenging eye conditions. Polymeric NPs are particularly effective due to their small size, biocompatibility and the capacity to encapsulate a diverse range of therapeutic agents including hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs by improving corneal permeability, prolonging residence time on the ocular surface and allowing for site-specific delivery. These nanocarriers significantly enhance drug bioavailability and therapeutic outcomes. In addition, polymeric NPs can be engineered to bypass ocular barriers and reach deeper tissues such as the posterior segment of the eye, thereby offering potential solutions for treating retinal diseases. Importantly, their sustained-release properties reduce the need for frequent administration, which not only improves patient compliance but also minimizes systemic side effects and toxicity. As a result, polymeric NPs represent a transformative advancement in ophthalmic drug delivery, offering a promising platform for developing next-generation therapies aimed at achieving long-term efficacy, safety and patient satisfaction.

Use of AI and AI-assisted technologies

Not applicable.